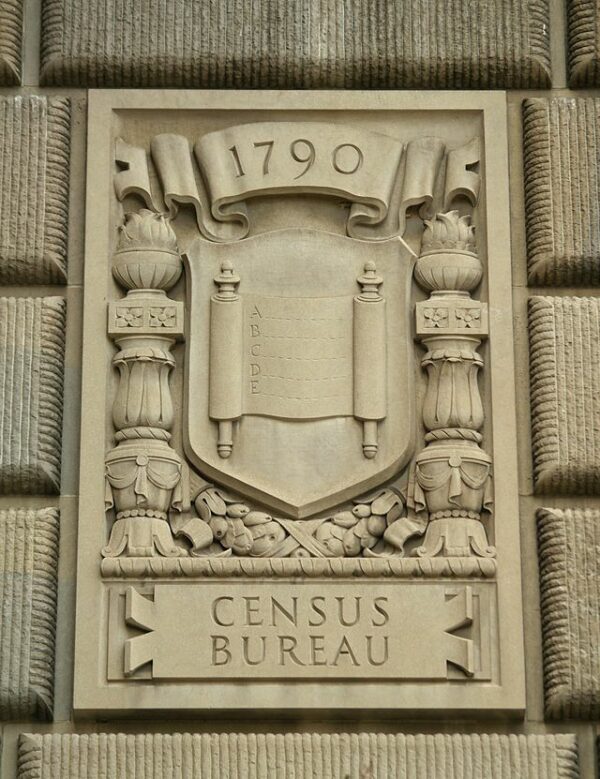

On August 2, 1790, the United States of America took its first count of the population. The U.S. Constitution ratified in 1789, mandated that a census be conducted to enumerate the people to apportion seats in the House of Representatives and assess direct taxes among the states. On that date, the tally began.

“No one knew precisely how many people lived in the United States when Washington became president, Mount Vernon writes. “Although the Articles of Confederation called for a triennial census to be used to divide the tax burden among the states, those enumerations never materialized. Ratified in 1788 and implemented the following year, the U.S. Constitution mandated that “Representatives and direct Taxes shall be apportioned among the several States . . . according to their respective Numbers, which shall be determined by adding to the whole Number of free Persons . . . and excluding Indians not taxed, three fifths of all other Persons.” The ‘other persons’ were the enslaved.

The Constitution also stipulated that the census would be decennial and that the first enumeration was to be completed “within three Years after the first Meeting of the Congress of the United States,” which convened in March 1789. Although Sweden was the first country to institute a regular national census, in 1749, the United States was the first to do for the purpose of continually reapportioning legislative seats (in the House of Representatives) to reflect changes in the size and geographic distribution of the population to ensure equitable representation.

Congress took up the matter of the census in its second session, and “An Act providing for the enumeration of the Inhabitants of the United States” became law on March 1, 1790. James Madison, the influential Virginia congressman and future president, had pressed for the census to include queries about respondents’ occupations “for ascertaining the component classes of the Society, a kind of information extremely requisite to the Legislator” who sought to better serve the needs of his constituents. Although Madison’s proposal was included in the bill passed by the House of Representatives, the Senate dismissed his proposal as “a waste of trouble.”

The bill that Washington signed into law specified that the census would include only the names of heads of households and an enumeration of persons divided into five categories: free white males age sixteen and older; free white males under the age of sixteen; free white females; all other free persons; and slaves. The census differentiated white males, but not females, by age because adult white men were widely understood to be the source of a nation’s military and economic power. The category “other free persons” included free African Americans, mixed race people, and Native Americans who lived among the white population.”

After the all-important counting was finished, the total population recorded in the fledgling nation was approximately 3.9 million people, with Virginia being the most populous state and Vermont the least inhabited.

The significance of the first U.S. census extended beyond its immediate impact on political representation and taxation. It established a precedent for conducting regular population counts every ten years, as required by the Constitution. Like so many things Americans take for granted, the first census help set a standard for those that followed, laying the foundation to expand the scope of data collected and providing valuable information for government planning, resource allocation, and demographic research. The census remains a vital tool in understanding the changing characteristics of the American population and continues to shape various aspects of public policy to this day.