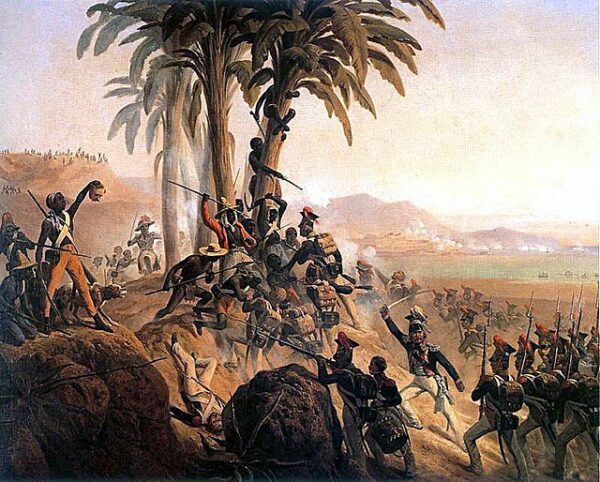

On August 22, 1791, “The Pearl of the Antilles,” the French colony of Saint Domingue erupted in flames. The Haitain Revolution had begun as the enslaved held in bondage on the world wealthiest colony fought for their freedom.

Spanning from 1791 to 1804, The Haitian Revolution stands as one of the most significant and successful slave uprisings in history, leading to the establishment of the independent nation of Haiti. Rooted in the oppressive conditions faced by enslaved Africans, the revolution was a pivotal moment that reshaped the Western Hemisphere and challenged the prevailing notions of race, equality, and colonial power.

The revolution emerged against the backdrop of enlightenment ideas of liberty, equality, and the rights of man that had spread through France and its colonies. Slaves on Saint-Domingue, inspired by these ideals and driven by their own desire for freedom, organized and revolted against their oppressors. The catalyst for the uprising was the Vodou ceremony held in August 1791, led by figures like Dutty Boukman and Cecile Fatiman, which marked the beginning of a widespread slave rebellion. The initial focus was on obtaining personal freedom and rights, but the movement quickly evolved into a struggle for full emancipation and self-determination.

The wealth of the island, writes Black Past, “came largely because of the island’s production of sugar, coffee, indigo, and cotton generated by an enslaved labor force. When the French Revolution broke out in 1789 there were five distinct sets of interest groups in the colony. There were white planters—who owned the plantations and the slaves—and petit blancs, who were artisans, shop keepers and teachers. Some of them also owned a few slaves. Together they numbered 40,000 of the colony’s residents. Many of the whites on Saint Domingue began to support an independence movement that began when France imposed steep tariffs on the items imported into the colony. The planters were extremely disenchanted with France because they were forbidden to trade with any other nation. Furthermore, the white population of Saint Domingue did not have any representation in France. Despite their calls for independence, both the planters and petit blancs remained committed to the institution of slavery.

The three remaining groups were of African descent: those who were free, those who were enslaved, and those who had run away. There were about 30,000 free black people in 1789. Half of them were mulatto and many of them were wealthier than the petit blancs. The slave population was close to 500,000. The runaway slaves were called maroons; they had retreated deep into the mountains of Saint Domingue and lived off subsistence farming. Haiti had a history of slave rebellions; the enslaved were never willing to submit to their status and with their strength in numbers (10 to 1) colonial officials and planters did all that was possible to control them. Despite the harshness and cruelty of Saint Domingue slavery, there were slave rebellions before 1791. One plot involved the poisoning of masters.

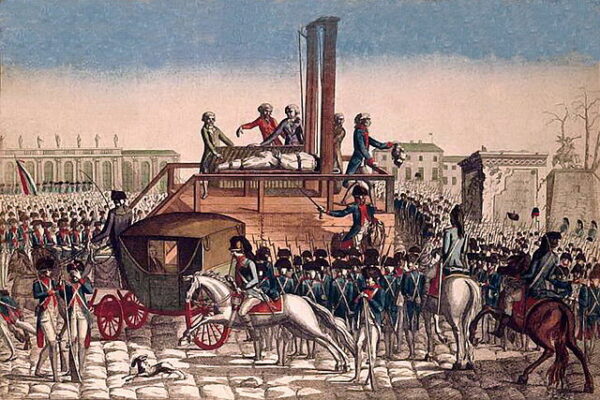

Inspired by events in France, a number of Haitian-born revolutionary movements emerged simultaneously. They used as their inspiration the French Revolution’s “Declaration of the Rights of Man.” The General Assembly in Paris responded by enacting legislation which gave the various colonies some autonomy at the local level. The legislation, which called for “all local proprietors…to be active citizens,” was both ambiguous and radical. It was interpreted in Saint Domingue as applying only to the planter class and thus excluded petit blancs from government. Yet it allowed free citizens of color who were substantial property owners to participate. This legislation, promulgated in Paris to keep Saint Domingue in the colonial empire, instead generated a three-sided civil war between the planters, free blacks, and the petit blancs. However, all three groups would be challenged by the enslaved black majority which was also influenced and inspired by events in France.

Led by former slave Toussaint l’Overture, the enslaved would act first, rebelling against the planters on August 21, 1791. By 1792 they controlled a third of the island. Despite reinforcements from France, the area of the colony held by the rebels grew as did the violence on both sides. Before the fighting ended 100,000 of the 500,000 blacks and 24,000 of the 40,000 whites were killed. Nonetheless the former slaves managed to stave off both the French forces and the British who arrived in 1793 to conquer the colony, and who withdrew in 1798 after a series of defeats by l’Overture’s forces. By 1801 l’Overture expanded the revolution beyond Haiti, conquering the neighboring Spanish colony of Santo Domingo (present-day Dominican Republic). He abolished slavery in the Spanish-speaking colony and declared himself Governor-General for life over the entire island of Hispaniola.”

Eventually, Napoleon would send tens of thousands of troops in an attempt at reclaiming the colony, but the Haitians would not back down.

The conflict was marked by its brutality, involving both internal and external forces. Slaves, along with some free people of color, fought against the French colonial authorities and planters. They faced not only the military might of France but also fierce opposition from other European powers, as well as local white and mixed-race elites who sought to preserve their interests.

France’s failure to recapture their colony had marked impact on North America, especially after Napoleon gave up on controlling colonies in the Western Hemisphere and sold his country’s holdings in the Louisiana Territory to the United States.

The revolution’s significance extends beyond its military victories and territorial control, however. It also challenged the notion of inherent racial hierarchy and demonstrated the power of enslaved individuals to organize and fight for their freedom against overwhelming odds. The defeat of the French, the Spanish, and the British forces signaled a seismic shift in the geopolitical landscape of the Caribbean. In 1804, Haiti declared itself the world’s first black republic and the second independent nation in the Americas, after the United States.

The Haitian Revolution had profound global implications, inspiring other anti-colonial and abolitionist movements and forcing the colonial powers to reassess their colonial practices, and striking fear into the hearts of American slaveholders who began to fear a massive insurrection sparked by its ideals coming to the continent. When Confederates declared secession in 1860, the fear of the Haitian Revolution coming to the United States under Abraham Lincoln’s presidency played a key role in their justifications for leaving the Union.