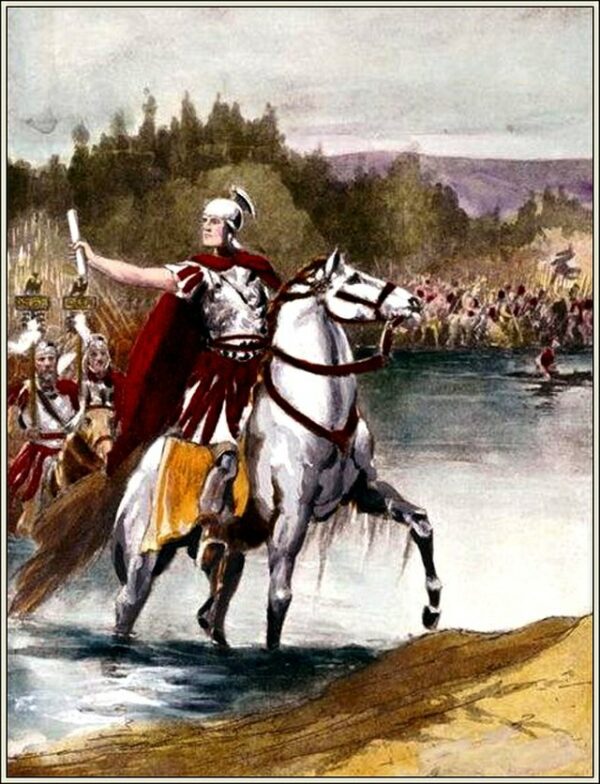

Julius Caesar’s crossing of the Rubicon on January 10, 49 BC, marked a defining moment in Roman history, heralding a seismic shift in the Republic’s power dynamics.

The Rubicon, a river that demarcated the boundary between Cisalpine Gaul and Italy proper, was more than a geographical line—it was a legal red line that generals were forbidden to cross with an army. Caesar stood at this precipice, torn between disbanding his legions and returning to Rome as a civilian or marching into Italy in defiance of the Senate’s edict that had passed three days prior that effectively declared him to be an enemy of Rome.

Though the crossing of the river Rubicon marked the beginning of the Roman Civil War, writes one historian, it was just one moment in the conflict between Caesar and fellow Roman statesman and general Pompey (Gnaeus Pompeius Magnus) that had been growing for years. The two men were temporary allies, part of the so-called Great Triumvirate. However, when their third ally, Marcus Crassus, died shortly after the death of Julia, Caesar’s daughter and Pompey’s wife, the pact was essentially finished.

By that time (53 BCE) Caesar and Pompey’s divergent contexts put them even more at odds. Caesar was conquering Gaul, gaining prestige and money, and garnering goodwill from the Roman people. Pompey, on the other hand, remained in Rome despite his active command in Spain, and was increasingly aligning with Senate conservatives who opposed Caesar fiercely and at all costs.

Three years later, the situation was growing untenable. Caesar retained his army in Gaul, even though his command there was winding down. His allies in Rome obstructed senatorial attempts to make him give up his army and return as a private citizen.

All Caesar wanted, he claimed, was to run for consul while retaining his military command and to receive a military triumph in Rome to celebrate his conquests. Pompey and much of the Senate, for their part, saw an emerging autocrat making demands and amassing an army blinded by loyalty.

Caesar was to some degree hamstrung, though. He knew the Senate would likely not accept his fair election as consul even if he complied with their demands, and senators opposing him had increasingly disregarded the Republic’s legal processes as the conflict grew.

As Caesar pondered the weight of his choice on the Rubicon’s northern banks in January 49 BCE, he faced an irreversible decision. The term “crossing the Rubicon” has since epitomized the point of no return. His deliberate act of rebellion against the Senate was tantamount to a declaration of war against the Republic, igniting a chain of civil conflicts that would culminate in the Republic’s demise and the Empire’s ascent.

The ripple effects of Caesar’s choice were staggering, triggering political and societal turmoil within Rome. Caesar emerged from the ensuing civil wars as the unchallenged dictator, yet his ascent sparked fervent discussions about power balances and the integrity of Republican institutions.