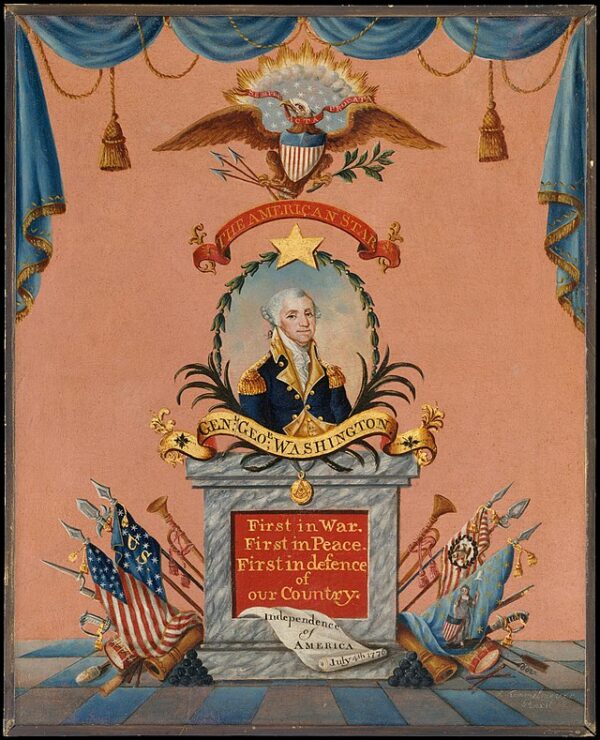

On February 4, 1789, George Washington unanimously won the Electoral College, becoming the first winner of a presidential election.

Washington’s reluctance to assume the presidency further solidified his image as a leader of virtue and selflessness and, in many ways, contributed to the unanimity. He had retired to his estate at Mount Vernon to live a life away from the political arena. However, the call to serve his country once more proved irresistible, as the nation’s leaders and citizens alike implored him to accept the role of president. Washington’s sense of duty ultimately prevailed, and he embarked on the journey to New York City, then the capital, to take the oath of office. His inauguration on April 30, 1789, attended by scores of Americans who viewed Washington as the embodiment of their hopes and ideals, set the standard for the American presidency.

As president, Washington was acutely aware of the precedents his administration would set for future generations. He approached his duties with a deliberate and cautious mindset, understanding that his actions would establish traditions and norms for the office of the presidency. His establishment of a Cabinet, although not explicitly provided for in the Constitution, was a strategic move to create a group of advisors from different regions and with diverse viewpoints. This decision underscored his commitment to a balanced and inclusive government, a principle that remains integral to the American political system.

Washington’s foreign policy decisions also demonstrated his foresight and dedication to American sovereignty. He navigated the treacherous waters of international relations with a focus on neutrality, recognizing the precarious position of the United States in a world of European conflicts. The Proclamation of Neutrality in 1793 exemplified his commitment to keeping the young nation out of foreign entanglements, a stance that would influence American foreign policy for years to come. His leadership during this period ensured that the United States would have the opportunity to grow and strengthen internally before engaging extensively on the international stage.

Upon the completion of his second term, Washington set yet another enduring precedent by voluntarily stepping down from power. His decision to retire after two terms established an informal rule that was followed by his successors until Franklin D. Roosevelt’s four-term presidency, after which the 22nd Amendment to the Constitution made it law.

Washington’s farewell address provided sage advice on unity, the dangers of political factions, and the importance of morality in governance. His presidency, marked by wisdom and restraint, laid the foundation for the executive branch and offered a model of leadership that has inspired countless leaders in the centuries that followed, proving the electors who met on this date in 1789 wise in their choice.