In May 1919, the American businessman, Raymond Orteig, wanted to promote the first flight across The Atlantic Ocean. He announced, “As a stimulus to the courageous aviators, I desire to offer … a prize of $25,000 to the first aviator of any Allied country crossing the Atlantic in one flight, from Paris to New York or New York to Paris, all other details in your care.”

The Minnesota Historical Society notes that it took over five years for someone to have the courage to try, but it was a disaster. “On Sep 15, 1926, French flying ace René Fonck and his crew attempted to take off from Roosevelt Field in New York, only to crash at the end of the runway, killing two of the four crew members.”

That’s where Charles Lindbergh came in. Born in Detroit, Michigan in 1902, Lindbergh developed a passion for aviation at a young age. He worked as a barnstormer and airmail pilot before he decided he wanted to claim Orteig’s Prize.

When he learned of Fonck’s failure, Charles Lindbergh began planning his own flight to Paris. He figured that “a nonstop flight between New York and Paris would be less hazardous than flying mail for a single winter” and spoke with some St. Louis business owners about funding his flight.

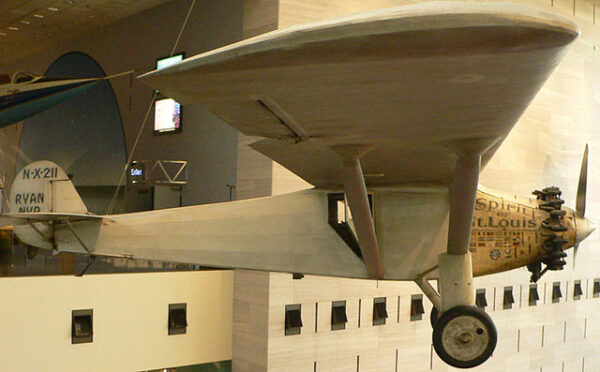

According to one account, “after several inquiries with other airplane manufacturers, Lindbergh decided to work with Ryan Aeronautical Company in San Diego, California. Ryan quoted Lindbergh and his backers $10,580 to build a single-engine monoplane powered by a Wright Whirlwind J-5 engine in 60 days.

From the start, Lindbergh wanted to make the flight by himself because of his concern about overloading the airplane. Lindbergh told Ryan chief engineer Donald Hall that “I’d rather have extra gasoline than an extra man.”

The two men worked together to design every aspect of the airplane which would become known as Spirit of St. Louis, named in honor of the men who provided the funding for the project. Lindbergh felt that they should ‘give first consideration to efficiency in flight; second, to protection in a crack-up; third, to pilot comfort.'”

On May 20, 1927, Lindbergh readied himself to make aviation history. He left Roosevelt Field, the same place where disaster had struck a year prior, and headed toward France. “The Spirit of St. Louis accelerated down the runway at Long Island, New York, and took off into the sky while a crowd of 500 watched. The plane barely cleared the telephone wires at the end of the strip,” writes Space.com.

“Lindbergh flew over Cape Cod and Nova Scotia, reaching the ocean as the sun set. Fog thickened in the night sky, and sleet formed on his plane when he attempted to pass through the clouds. He struggled with drowsiness, fighting to stay awake as he sometimes flew only 10 feet above the ocean.

A tiny fishing boat provided the first sign that he had reached Europe, and within an hour he had reached land. He flew about 1,500 feet (460 meters) over Ireland and England, then headed toward France as the weather cleared. Darkness fell again as he passed over the coast of his target country.

After traveling more than 3,600 miles (5,800 kilometers) in 33.5 hours, Lindbergh landed safely in Paris. A crowd of 100,000 swarmed around the plane, hoisting the pilot on their shoulders and cheering his achievement. The papers called him the ‘Lone Eagle’ and ‘Lucky Lindy.'”

Lindbergh’s daring made him a hero and a worldwide celebrity. He claimed his prize from Orteig in a ceremony a few weeks later.