On June 4, 1876, The Transcontinental Express, also called “The Lightning Express,” made history and it puttered into San Francisco a mere 83 hours or so after it had left New York City.

“That any human being could travel across the entire nation in less than four days was inconceivable to previous generations of Americans,” The History Channel writes. “During the early 19th century, when Thomas Jefferson first dreamed of an American nation stretching from “sea to shining sea,” it took the president 10 days to travel the 225 miles from Monticello to Philadelphia via carriage. Even with frequent changing of horses, the 100-mile journey from New York to Philadelphia demanded two days hard travel in a light stagecoach. At such speeds, the coasts of the continent-wide American nation were months apart. How could such a vast country ever hope to remain united?

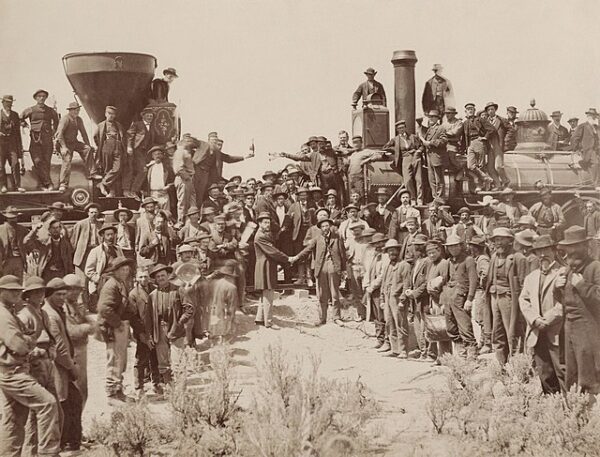

As early as 1802, Jefferson had some glimmer of an answer. “The introduction of so powerful an agent as steam,” he predicted, “[to a carriage on wheels] will make a great change in the situation of man.” Though Jefferson never saw a train in his lifetime, he had glimpsed the future with the idea. Within half a century, America would have more railroads than any other nation in the world. By 1869, the first transcontinental line linking the coasts was completed. Suddenly, a journey that had previously taken months using horses could be made in less than a week.

Five days after the transcontinental railroad was completed, daily passenger service over the rails began. The speed and comfort offered by rail travel was so astonishing that many Americans could scarcely believe it, and popular magazines wrote glowing accounts of the amazing journey. For the wealthy, a trip on the transcontinental railroad was a luxurious experience. First-class passengers rode in beautifully appointed cars with plush velvet seats that converted into snug sleeping berths. The finer amenities included steam heat, fresh linen daily and gracious porters who catered to their every whim. For an extra $4 a day, the wealthy traveler could opt to take the weekly Pacific Hotel Express, which offered first-class dining on board. As one happy passenger wrote, “The rarest and richest of all my journeying through life is this three-thousand miles by rail.”

The trip was a good deal less speedy and comfortable for passengers unwilling or unable to pay the premium fares. Whereas most of the first-class passengers traveled the transcontinental line for business or pleasure, the third-class occupants were often emigrants hoping to make a new start in the West. A third-class ticket could be purchased for only $40–less than half the price of the first-class fare. At this low rate, the traveler received no luxuries. Their cars, fitted with rows of narrow wooden benches, were congested, noisy and uncomfortable. The railroad often attached the coach cars to freight cars that were constantly shunted aside to make way for the express trains. Consequently, the third-class traveler’s journey west might take 10 or more days.”

10 days, however, was nothing compared to the grueling travel without the transcontinental railroad. A trip by wagon train might take four to five months, depending on the number of people traveling by train, which route was taken, and the weather.

“Travel by stagecoach was much shorter,” writes one historian, “usually only about four weeks. A trip by stagecoach was also much more expensive. Both wagon trains and stagecoaches would usually leave from Independence, Missouri, so if travelers were coming from further east, that travel time would be added to the trip.

A voyage by ship from New York to California in the mid-1800s, was possible via Colombia’s Isthmus of Panama (where voyagers would take a train from the Atlantic Ocean to the Pacific Ocean and then board another ship). That trip would normally take about 45 days. The alternative was to sail around the tip of South America; that voyage usually took nearly 200 days. “

Promoters understood the publicity making the trek across the nation would create. “It was arranged and paid for by Henry Jarrett, one of the principals of Jarrett & Palmer, the firm that managed the Booth Theater in New York City and produced theatrical performances all over the world.”

Railroad companies understood that the Transcontinental’s trip would show of the speed and comfort of “modern travel.” After the train made it to San Francisco, other companies began launching their own “lightning trains” and America truly became connected from sea to shining sea.