On June 13, 1971, The New York Times began publishing a series of articles based on the Pentagon Papers, a top-secret Department of Defense study of U.S. political and military involvement in Vietnam from 1945 to 1967.

It was a bombshell report.

The Pentagon Papers were commissioned by Secretary of Defense Robert McNamara in 1967, and revealed that successive administrations had misled the public about the scope and aims of the Vietnam War, igniting a firestorm of controversy and legal battles.

Comprising 7,000 pages of detailed analyses, the study documented the decision-making processes that had led the United States into a complex and ultimately disastrous conflict in Southeast Asia. Despite their classified status, the papers were photocopied by Daniel Ellsberg, a former military analyst, who had grown disillusioned with the war.

Ellsberg initially approached members of Congress to release the documents, but when that strategy failed, he turned to the press. The New York Times began its publication with a dramatic front-page headline and a series of articles that exposed the stark contrast between public statements and private deliberations. Key revelations included evidence that the government had systematically lied about the war’s progress and its prospects for success, as well as the clandestine expansion of military actions into neighboring countries such as Laos and Cambodia.

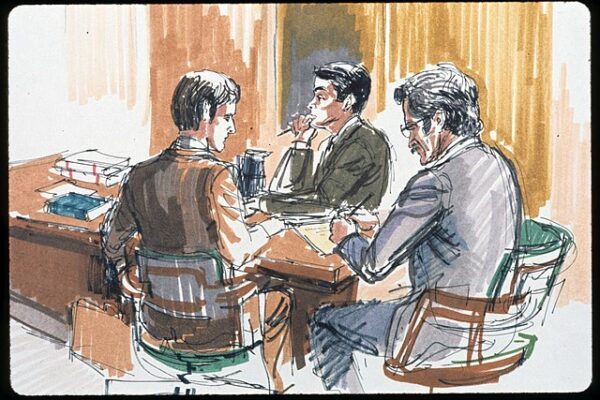

The publication of the Pentagon Papers quickly led to a significant legal showdown. The Nixon administration, citing national security concerns, sought a court injunction to halt further publication. This led to a landmark Supreme Court case, New York Times Co. v. United States, in which the Court upheld the right of the press to publish the documents. The 6-3 decision was a resounding affirmation of the First Amendment, declaring that prior restraint – government action that prevents speech or other expression before it can take place – was unconstitutional in this instance.

The implications of the Pentagon Papers were profound. Public trust in the government, already eroding due to the ongoing war and domestic turmoil, was further undermined. The revelations fueled widespread opposition to the Vietnam War and intensified scrutiny of U.S. foreign policy. The image of a government that had consistently deceived its citizens led to a significant shift in public opinion and increased pressure to end U.S. involvement in Vietnam.

Moreover, the Pentagon Papers had a lasting impact on journalism and government transparency. The episode is often cited as a triumph of investigative journalism and the role of the free press in holding government accountable. It underscored the critical function of the media as a watchdog, capable of uncovering truths that those in power might prefer to keep hidden.

For Daniel Ellsberg, the release of the Pentagon Papers marked him as both a hero and a traitor, depending on one’s perspective. He was charged with theft, conspiracy, and violations of the Espionage Act, facing a potential sentence of over 100 years in prison. However, his trial was dismissed in 1973 due to government misconduct, including illegal wiretapping and evidence tampering by the Nixon administration.

In the broader context of American history, the Pentagon Papers episode exemplifies the tension between national security and freedom of the press. It highlighted the ethical dilemmas faced by whistleblowers and the journalists who report their disclosures. The case remains a cornerstone in debates over the balance between government secrecy and the public’s right to know, especially in times of conflict.