According to tradition, on June 15, 1752, Benjamin Franklin performed his most famous science experiment, one that helped make him renowned and is most often associated with him.

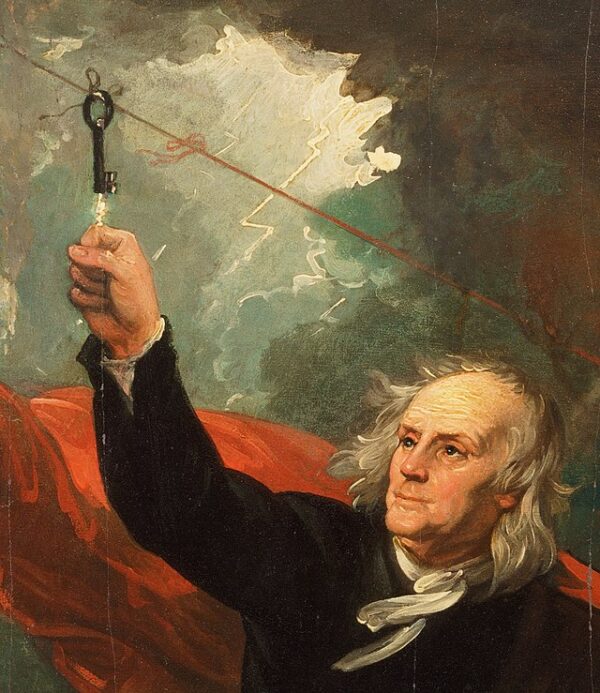

As the skies of Philadelphia began to darken with the approaching of a thunderstorm and many of his fellow citizens took cover, Franklin walked outside with a handful of items: a kite, some string, a metal key, some wire, and a Leyden jar, which could store an electrical charge. He intended to prove that lightning was a form of electricity.

Forbes writes, “It all started with a letter. In 1750, Franklin wrote to his friend and scientific colleague Peter Collinson, who lived in London. He told Collinson about his latest brilliant scientific idea: a lightning rod. By sticking a 30-foot metal rod into the air during a storm, Franklin suggested, you could attract a bolt of lightning and then divert the energy into a Leyden Jar, an apparatus for storing an electric charge.

Letters between scientists weren’t really private correspondence in those days. A letter about a new experiment or theory tended to get passed around the scientific community, or copied and sent to colleagues. By the summer of 1752, Franklin’s letter had made it to Paris, where it had electrified the scientific community there thanks to French physicist Thomas Dalibard’s translation. And in fact, Dalibard tried out Franklin’s lightning rod before Franklin himself could do it, on May 10, 1752.

A second French scientist, recorded only as M. Delor, replicated the experiment a week later. Franklin’s lightning rod was a success, but he’d still never seen it in action – and he hadn’t yet heard of its success. But by June 1752, he believed he had found an easier, more cost-effective way to set up the experiment: rather than building a tall metal spike, he could just fly a kite with a wire and a key attached.”

The Franklin Institute details what happened next, clearing up some myths along the way: “Franklin’s kite was not struck by lightning. If it had been, he probably would have been electrocuted, experts say. Instead, the kite picked up the ambient electrical charge from the storm.

Here’s how the experiment worked: Franklin constructed a simple kite and attached a wire to the top of it to act as a lightning rod. To the bottom of the kite he attached a hemp string, and to that he attached a silk string. Why both? The hemp, wetted by the rain, would conduct an electrical charge quickly. The silk string, kept dry as it was held by Franklin in the doorway of a shed, wouldn’t.

The last piece of the puzzle was the metal key. Franklin attached it to the hemp string, and with his son’s help, got the kite aloft. Then they waited. Just as he was beginning to despair, Priestley wrote, Franklin noticed loose threads of the hemp string standing erect, “just as if they had been suspended on a common conductor.”

Franklin moved his finger near the key, and as the negative charges in the metal piece were attracted to the positive charges in his hand, he felt a spark.

“Struck with this promising appearance, he immediately presented his knucle [sic] to the key, and (let the reader judge of the exquisite pleasure he must have felt at that moment) the discovery was complete. He perceived a very evident electric spark,” Priestley wrote.

A few months later, Franklin wrote to his local newspaper telling the world what he’d done, and a legend was born.

Along with serving his country during the Revolution and signing the Declaration of Independence, Benjamin Franklin made dozens of civic contributions, including the creation of a library, insurance company, city hospital, and the University of Pennsylvania.

Americans have long viewed June 15 as Kite Day to celebrate his achievements.