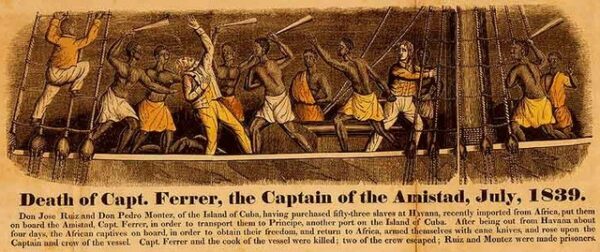

On July 2, 1839, over 50 captives on a slave ship named La Amistad threw off their chains and seized control of the ship. Led by Joseph Cinqué, the Africans killed the ship’s captain and another crew member, demanding to be returned to Mendiland (now Sierra Leone). Nevertheless, the surviving Spanish crew tricked them. Instead, it sailed toward the United States, where the U.S. Navy intercepted the vessel off the coast, eventually steering it to New London, Connecticut.

Spanish authorities demanded the Africans be extradited to Cuba and tried for murder, but the ship’s arrival sparked an intense debate over slavery in the United States. Initially, Connecticut jailed the Africans and charged them with murder, but eventually, their case moved through the U.S. District and Circuit Courts.

Eventually, however, one of the greatest Americans of the period decided to step in. Just as his father had defended British soldiers wrongly accused of murder during the Boston Massacre, John Quincy Adams, by then a former president, took on the unpopular case, determined to fight on behalf of the enslaved in front of the Supreme Court.

The Massachusetts Historical Society writes, “While he offered opinions and advice on the Amistad case as early as September 1839, John Quincy Adams did not take a formal role until a year later. Abolitionists visited the former president at his home in Quincy on October 27, 1840 and convinced him to join the Amistad defense team when the case went before the U.S. Supreme Court. In his diary, Adams noted his reluctance to provide further legal counsel. “I endeavoured to excuse myself upon the plea of my age and inefficiency—of the oppressive burden of my duties as a member of the House of Representatives, and my inexperience after a lapse of more than thirty years . . . before judicial tribunals.” However, the abolitionists “urged me so much and represented the case of those unfortunate men as so critical, it being a case of life and death, that I yielded.”

The trial opened in February 1841. John Quincy Adams began his oral arguments for the defense on the 24th, speaking for “four hours and a half, with sufficient method and order to witness little flagging of attention, by the judges or the auditory.” Pleased with his performance, he modestly assessed: “I did not I could not answer public expectation—but I have not yet utterly failed.” Adams returned to the court on March 1 to conclude his argument on behalf of the Amistad Africans and spoke for another four hours. The court’s opinion, delivered on March 9, ruled that the Africans were free and could return home.

As he revised for publication his oral arguments in the Amistad case, John Quincy Adams mused in his diary on the current state of the emancipation cause in the United States. “The world, the flesh, and all the devils in hell are arrayed against any man, who now, in this North-American Union, shall dare to join the standard of Almighty God, to put down” the issue of slavery. He lamented that his own physical infirmities prevented him from doing more to further the cause. “What can I, upon the verge of my seventy-fourth birth-day, with a shaking hand, a darkening eye, a drowsy brain, and with all my faculties, dropping from me, one by one, as the teeth are dropping from my head . . . what can I do for the cause of God and Man? for the progress of human emancipation? . . . Yet my conscience presses me on.” The following year, Adams recorded that his continued opposition to slavery produced considerably different reactions in the North and South. While northerners routinely wrote to him asking for an autograph, the letters he received from southerners often contained “insult, profane obscenity and filth.”

The defense proffered by John Quincy Adams became one of legend. “The prosecution and defense presented their cases on February 22 and 23, 1841. On the following day, Adams entered the Supreme Court chambers in the U.S. Capitol to deliver the closing remarks for the defense. He spoke for four and a half hours, discoursing at length on the humanity and natural rights of the slaves. He also criticized the Van Buren administration for supporting the “lawless and tyrannical” Spanish, who were engaging in the human trafficking of enslaved persons, noted The Bill of Rights Institute.

“Unexpectedly, Justice Philip Barbour died that night, and so the Court recessed until March 1. That day, Adams spoke for an additional four hours as he continued to present his closing argument. Several times he pointed to the copy of the Declaration of Independence hanging in the chambers and asserted that the Africans were entitled to all the rights and freedoms embodied in the “Law of Nature and of Nature’s God on which our fathers placed our national existence.’ He finished by appealing to the justices to follow the example set by their predecessors on the Court, such as Chief Justice John Marshall, in dispensing justice. He asked for a ‘fervent petition to heaven, that every member of it may go to his final ascent with as little of earthly frailty to answer for as those illustrious dead.'”

Quincy’s speech has become a lesson in rhetoric and was performed by Anthony Hopkins in the famous film “Amistad” in 1997.

On March 9, the Court ruled 7-1 in favor of Adams, freeing the Africans. They were allowed to return home with the help of privately raised funds. In November, they set sail for Africa. Adams’s dedication to justice extended beyond the case, as he never billed his client for his services.

The decision was a significant victory for the abolitionist movement and marked a turning point in the fight against the international slave trade. The Amistad mutiny highlighted the resilience and determination of those who were enslaved, as well as the international outrage against the institution of slavery. It remains an important chapter in the history of human rights and the struggle for freedom.