On July 14, 1789, during the early stages of the French Revolution, a state prison on the east side of Paris, the Bastille, was attacked by an angry and aggressive mob. The event marked a turning point in the history of France.

The British Library writes, “A medieval fortress, the Bastille’s eight 30-metre-high towers, dominated the Parisian skyline. When the prison was attacked it actually held only seven prisoners, but the mob had not gathered for them: it had come to demand the huge ammunition stores held within the prison walls. When the prison governor refused to comply, the mob charged and, after a violent battle, eventually took hold of the building. The governor was seized and killed, his head carried round the streets on a spike. The storming of the Bastille symbolically marked the beginning of the French Revolution, in which the monarchy was overthrown and a republic set up based on the ideas of ‘Liberté, égalité, fraternité’ (the French for liberty, equality and brotherhood). In France, the ‘storming of the Bastille’ is still celebrated each year by a national holiday.”

The storming of the Bastille had significant symbolic meaning for the revolutionaries. It represented a triumph of the people over an oppressive symbol of royal power. Following the event, the French monarchy was increasingly challenged, and the revolutionary ideas gained momentum, leading to widespread unrest and eventually the abolition of the monarchy.

Even before 1789, however, ordinary people in France and other places knew that they did have some power if they acted together. The memoirs of the French glassfitter Jacques Ménétra, one of the few working people of the time to keep a record of his life, recount many times when he and others joined together to confront the authorities. When flour prices soared, making bread too costly for poor families, crowds, often led by women, seized grain shipments and forced merchants to sell their goods at what the population considered a fair price. Ménétra and other artisans knew how to act together to pressure their employers for higher wages and to guard their jobs from outsiders who might undercut their wages. When the French king tried to get the courts to authorize new taxes, law clerks roused urban populations to demonstrate against these violations of traditional rights.

In 1789, French King Louis XVI, facing an unparalleled financial situation, explained The National Endowment of the Humanities, “was compelled to raise taxes. He summoned the Estates General, a long-forgotten elected assembly that had not been convened in 175 years. The king hoped that deputies chosen by his subjects would agree to raise the taxes to stave off bankruptcy. The elections were an unprecedented opportunity for the population to express their opinions. The same local assemblies that chose deputies for the Estates General also drafted cahiers de doléances, lists of complaints and demands for reform. The cahiers left no doubt that a majority wanted constitutional limits on the king’s powers, protections for individual rights, and an assembly chosen by voters to make the country’s laws.

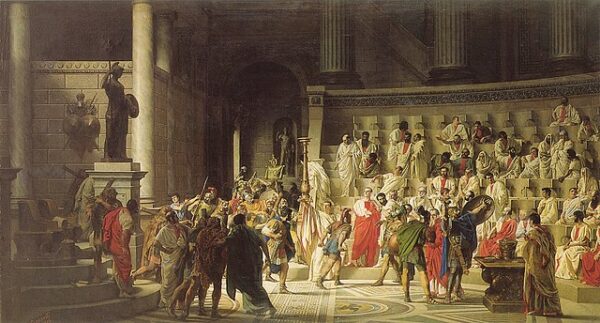

Louis XVI, who had been raised to think he was divinely chosen to rule his kingdom, could not accept such drastic changes. When the elected deputies of the Estates General renamed themselves the “National Assembly” to assert their claim to be speaking for the entire population, the king prepared to use force to oppose them. Army regiments were brought from France’s frontiers to the capital. Fears mounted that they would be used to dissolve the Assembly and overawe the population, whose support for the deputies was unmistakable. On July 11, after weeks of tension, the king acted: He dismissed his chief minister, Jacques Necker, who had been trying valiantly to broker compromises. In the National Assembly, deputies passed defiant resolutions and braced themselves for arrest or worse.

At the news of Necker’s dismissal, the population in Paris poured into the streets. Crowds formed and attacked symbols of authority, starting with the barriers at the entrances to the city, where much-resented taxes on foodstuffs were collected. When royal troops charged a large gathering in the Tuileries park in the center of Paris on July 12, the crowd fought back, hurling stones at the soldiers. Alarmed commanders warned the royal court that their soldiers weren’t willing to open fire on their fellow citizens, but rumors of impending military action rubbed the population’s nerves raw. All through the day of July 13, large bands roamed the city, searching for arms and ammunition to defend themselves against an assault they expected to come at any moment.

On the morning of July 14, attention turned to the Bastille, a fortress whose medieval towers commanded the working-class neighborhood of the Faubourg Saint-Antoine. Completely obsolete as a military fortification, the Bastille had been used as a prison, but by 1789 it was rarely employed even for that purpose. It remained, however, a symbol of arbitrary royal power. And that day the Bastille attracted the crowd because it housed a store of gunpowder, which the citizenry needed if they were to fend off an armed attack. For several hours, the small detachment of soldiers defending the Bastille held off the crowd, killing about 100. Rather than deterring the people, the fortress’s resistance enraged them further. Led by some soldiers who had taken the side of the people, the crowd finally broke down the fortress’s main door and the garrison surrendered. The collective action of the ordinary men and women who made up the crowd—members of both sexes took part—had overcome the power of the king and his army.

As news of the dramatic events in Paris arrived in Versailles, about 12 miles away, the National Assembly deputies became increasingly nervous. Many of them feared this outbreak of violence would furnish a pretext for the king to send in his troops. A few years earlier, in 1780, a rampaging mob in London, just across the English Channel, had set fire to buildings, causing great damage and several hundred deaths. It was both a relief and a surprise when the deputies learned that the crowd, although it had massacred the commander of the Bastille and the acting mayor of Paris, was demanding above all that Louis XVI withdraw his soldiers and accept the Assembly’s authority to create a new national constitution. Through their collective action on July 14, which was followed by a wave of popular actions nationwide, the people of Paris settled the contest between the king and the people’s representatives.”

The storming of the Bastille ignited a fire that spread throughout France, setting the stage for a series of momentous events in the French Revolution. News of the audacious attack on the fortress quickly traveled across the country, kindling the flames of discontent and inspiring people in towns and villages to rise up against the monarchy.

The fall of the Bastille was more than a mere breach of stone walls; it represented the shattering of the Ancien Régime, the established order that King Louis XVI and his predecessors had long upheld.The power dynamic began to shift, with the monarchy losing its grip as the people asserted their demands for political change.

Emboldened by their triumph, the revolutionaries, primarily representing the Third Estate comprised of commoners, seized control of the government. They formed the National Assembly, a body that would shape the course of the revolution. The National Assembly enacted sweeping reforms, abolishing feudalism and drafting the Declaration of the Rights of Man and of the Citizen, a document that proclaimed fundamental human rights and liberties.

Yet, amidst the enthusiasm for change, the revolution descended into a dark chapter known as the Reign of Terror. Several years after the storming of the Bastille, from 1793 to 1794, a period of intense violence and political upheaval gripped the nation. Executions became frequent, and paranoia consumed the revolutionary leaders, resulting in the demise of many perceived enemies of the revolution, culminating in the Reign of Terror.

The storming of the Bastille proved to be a pivotal moment in history, unleashing a cascade of transformative events. In modern times, the storming of the Bastille is celebrated as a national holiday in France called Bastille Day (or La Fête nationale). It is observed on July 14 each year and commemorates the beginning of the French Revolution and the principles of liberty, equality, and fraternity.