On August 6, 1945, the world entered a new, terrifying realm of warfare. High above the clouds over Hiroshima, Japan, an American Boeing B-29 Superfortress bomber named The Enola Gay” carried its fateful payload. Inside, a crew understood that the weight of history rested on their successful mission, Operation Centerboard I. For over four years, the United States had been in a deadly conflict, costing thousands of lives, and what they carried, they were told, could not only end the war but potentially end all wars.

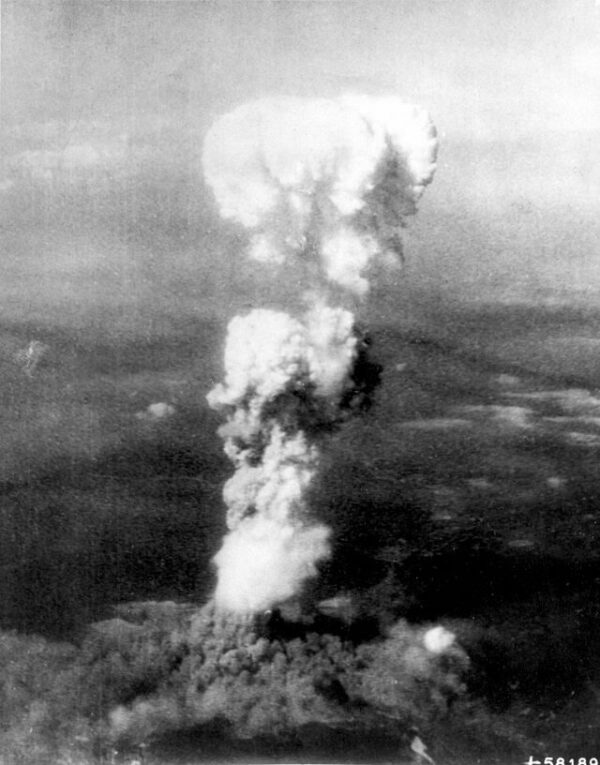

As they approached Hiroshima, a bustling city filled with unsuspecting civilians, a heavy silence hung in the air. The crew’s hearts pounded, contemplating the unimaginable devastation that awaited below. At the designated moment, they released “Little Boy,” an atomic bomb with incomprehensible power. The pilots watched as a brilliant flash pierced the sky, and a cloud mushroomed, engulfing the city. turning it to ruins in an instant.

The National Museum of Nuclear Science and History documented the words of the crew:

Pilot Paul Tibbets: “We turned back to look at Hiroshima. The city was hidden by that awful cloud… boiling up, mushrooming, terrible and incredibly tall. No one spoke for a moment; then everyone was talking. I remember (copilot Robert) Lewis pounding my shoulder, saying ‘Look at that! Look at that! Look at that!’ (Bombardier) Tom Ferebee wondered about whether radioactivity would make us all sterile. Lewis said he could taste atomic fission. He said it tasted like lead.”

Navigator Theodore Van Kirk recalls the shockwaves from the explosion: “(It was) very much as if you’ve ever sat on an ash can and had somebody hit it with a baseball bat… The plane bounced, it jumped and there was a noise like a piece of sheet metal snapping. Those of us who had flown quite a bit over Europe thought that it was anti-aircraft fire that had exploded very close to the plane.” On viewing the atomic fireball: “I don’t believe anyone ever expected to look at a sight quite like that. Where we had seen a clear city two minutes before, we could now no longer see the city. We could see smoke and fires creeping up the sides of the mountains.”

Tail gunner Robert Caron: “The mushroom itself was a spectacular sight, a bubbling mass of purple-gray smoke and you could see it had a red core in it and everything was burning inside. As we got farther away, we could see the base of the mushroom and below we could see what looked like a few-hundred-foot layer of debris and smoke and what have you… I saw fires springing up in different places, like flames shooting up on a bed of coals.”

The explosion annihilated the city of Hiroshima. 70,000 of 76,000 buildings were damaged or destroyed, and 48,000 were entirely wiped off the face of the planet. Between 70,000 to 80,000 Japanese were estimated to have died instantly, with tens of thousands more dying in the following weeks due to injuries and radiation exposure.

The decision to drop the bomb has been widely debated, but President Harry S. Truman rightfully believed that using nuclear weapons would bring a swift end to the war with Japan. He hoped to avoid the potentially catastrophic casualties that a full-scale invasion of the Japanese mainland would entail, estimated at hundreds of thousands, if not millions. World War II would be over in less than a month.

The aftermath of the bombing brought an era of heightened nuclear tensions and a global arms race, with the United States and the Soviet Union becoming the two superpowers at the forefront of this race. The event also triggered the establishment of the United Nations and intensified international efforts toward arms control and disarmament. To this day, the dropping of the atomic bomb on Hiroshima remains a subject of profound historical significance, sparking ongoing discussions about the appropriate use of force and the pursuit of peace in the face of conflict.