On August 17, 1807, Robert Fulton changed how Americans traveled, taking a steamboat between New York City and Albany and heralding the beginning of steam navigation on the Hudson River.

In 1801 Fulton met Robert R. Livingston, a signer of the U.S. Declaration of Independence. Before leaving to serve as the minister to France, Livingston had obtained a 20-year steamboat navigation monopoly within New York. The two men decided to join forces and build a steamboat in Paris using Fulton’s design. Britannica writes, “a 66-foot- (20-metre-) long boat with an eight-horsepower engine of French design and side paddle wheels. Although the engine broke the hull, they were encouraged by success with another hull. Fulton ordered parts for a 24-horsepower engine from Boulton and Watt for a boat on the Hudson, and Livingston obtained an extension on his monopoly of steamboat navigation.

Returning to London in 1804, Fulton advanced his ideas with the British government for submersible and low-lying craft that would carry explosives in an attack. Two raids against the French using his novel craft, however, were unsuccessful. In 1805, after Nelson’s victory at Trafalgar, it was apparent that Britain was in control of the seas without the aid of Fulton’s temperamental weapons. In the same year, the parts for his projected steamboat were ready for shipment to the United States, but Fulton spent a desperate year attempting to collect money he felt the British owed him.

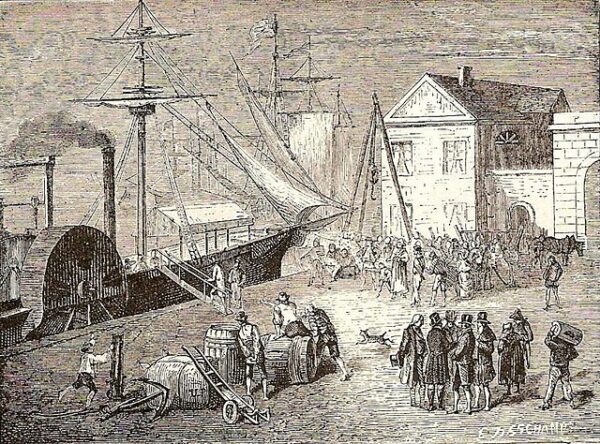

Arriving in New York in December 1806, Fulton at once set to work supervising the construction of the steamboat that had been planned in Paris with Livingston. He also attempted to interest the U.S. government in a submarine, but his demonstration of it was a fiasco. By early August 1807 a 150-foot-long Steamboat, as Fulton called it, was ready for trials. Its single-cylinder condensing steam engine (24-inch bore and four-foot stroke) drove two 15-foot-diameter side paddle wheels; it consumed oak and pine fuel, which produced steam at a pressure of two to three pounds per square inch. The 150-mile (240-km) trial run from New York to Albany required 32 hours (an average of almost 4.7 miles [7.6 km] per hour), considerably better time than the four miles per hour required by the monopoly. The passage was epic because sailing sloops required four days for the same trip.

After building an engine house, raising the bulwark, and installing berths in the cabins of the now-renamed North River Steamboat, Fulton began commercial trips in September. He made three round trips fortnightly between New York and Albany, carrying passengers and light freight. Problems, however, remained: the mechanical difficulties, for example, and the jealous sloop boatmen, who through “inadvertence” would ram the unprotected paddle wheels of their new rivals. During the first winter season he stiffened and widened the hull, replaced the cast-iron crankshaft with a forging, fitted guards over the wheels, and improved passenger accommodations. These modifications made it a different boat, which was registered in 1808 as the North River Steamboat of Clermont, soon reduced to Clermont by the press.”

The North River Steamboat became iconic and ended up playing a pivotal role in shaping the landscape of transportation and commerce during the early 19th century.

Fulton’s ship not only showcased the potential of steam propulsion but also contributed to the transformation of the American economy. Prior to its advent, river travel was often slow and dependent on natural currents and wind. The introduction of steam power drastically reduced travel times and enabled more efficient movement of goods and people. This innovation opened up new opportunities for trade, connecting previously isolated regions and bolstering economic growth along waterways. As a result, the North River Steamboat set a precedent for the integration of steam technology into transportation networks, leaving an indelible mark on the evolution of industrialization and commerce.

Beyond its technological significance, the North River Steamboat sparked a wave of interest and investment in steam-powered vessels. Its successful voyage demonstrated the commercial viability of steamboats, prompting entrepreneurs and engineers to design and construct their own variations of the technology. This led to the rapid expansion of steamboat services along rivers and coastlines, enhancing accessibility and connectivity across the United States. The North River Steamboat thus served as a catalyst for innovation, propelling the nation into an era of transportation revolution that laid the groundwork for modern maritime travel.