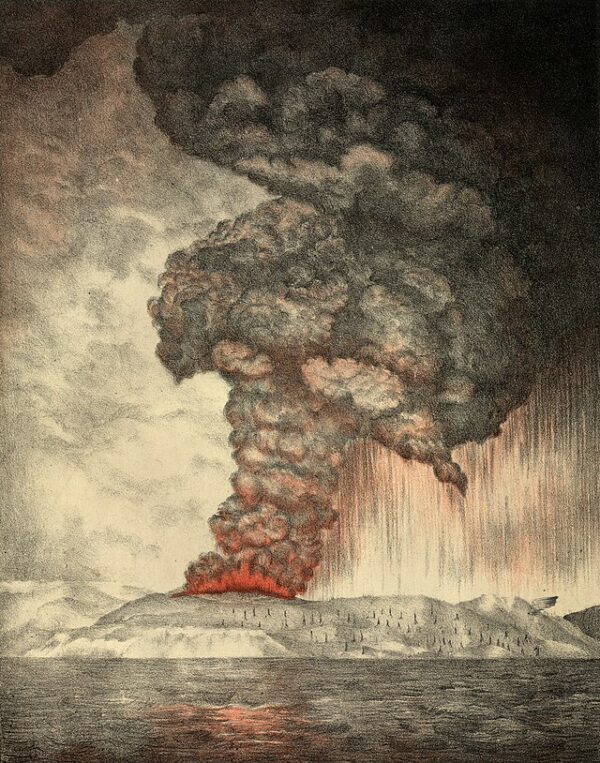

On August 26, 1883, the loudest sound ever recorded happened in Indonesia on a caldera situated in the Sunda Strait between the islands of Java and Sumatra in the Indonesian province of Lampung. The volcano known as Krakatoa erupted with such force that it shaped the world for months afterward.

Krakatoa was a chain of volcanic islands known for its picturesque beauty until disaster struck. The first signs of the impending catastrophe emerged in May 1883, as the volcano became increasingly active. Seismic activity surged, and a series of smaller eruptions presaged the main event. On August 26, the volcano unleashed its devastating might. The eruption began with a colossal explosion, tearing apart the island and launching a massive pyroclastic surge into the atmosphere. The resulting shockwave reverberated around the globe, generating atmospheric pressure waves that were detected as far away as England.

One witness described the event this way: “On the afternoon of the 26th there were violent explosions at Krakatoa, which were heard as far as Batavia. High waves first retreated, and then rolled upon both sides of the strait. During a night of pitchy darkness these horrors continued with increasing violence, augmented at midnight by electrical phenomena on a terrifying scale.”

The explosion unleashed a towering column of ash, smoke, and debris that ascended to staggering heights, visible from hundreds of miles away. As the column collapsed, a series of colossal tsunamis roared outward, devastating coastal communities and claiming over 36,000 lives. The ash and aerosols injected into the atmosphere created spectacular sunsets globally, painting the skies with vibrant colors.

The eruption released sulfur dioxide and other particles such as ash into the air, writes the Natural History Museum, which filtered the colours of the sunlight reaching the Earth. Different colours have different wavelengths, with red being the longest, violet the shortest and the others somewhere in between, following the order of a rainbow.

The volcanic particles were smaller than a micron, which is about a hundred times smaller than the thickness of a human hair. But they were slightly wider than the wavelength of red light, so once scattered, they absorbed the red light while allowing other colours to pass through. This resulted in surreal landscapes and many blue Moons.

The eruption had profound climatic consequences, altering global weather patterns for years. The ejected particles encircled the planet, reflecting sunlight and causing a noticeable drop in temperatures. The following year, 1884, became known as the “Year Without a Summer,” with disrupted agriculture, famines, and economic hardships reported across the world. The volcanic aftermath was etched into the collective memory and laid the groundwork for modern volcano monitoring and the understanding of volcanic impacts on a global scale.