On September 5, 1774, Americans took one step closer toward independence with the meeting of the First Continental Congress. As tensions with Great Britain escalated, the colonies recognized the necessity of a unified response to the increasingly oppressive British policies, which many colonists believed violated their rights as Englishmen.

This gathering was not a spontaneous event but the culmination of years of growing dissatisfaction among the colonies, particularly in response to what they perceived as unfair taxation and governance. The tipping point came with the passage of the Coercive Acts, known in the colonies as the Intolerable Acts, in early 1774. These acts were designed to punish Massachusetts for the Boston Tea Party, where American colonists had protested against the Tea Act by dumping a large shipment of British tea into Boston Harbor.

The Intolerable Acts included a series of measures that closed Boston Harbor, revoked the Massachusetts Charter, and imposed British military rule over the colony. These punitive laws were seen by the colonists not just as retribution against Massachusetts, but as a direct threat to the liberties of all the American colonies. The fear was that if Britain could so easily strip Massachusetts of its rights, it could do the same to any of the other colonies.

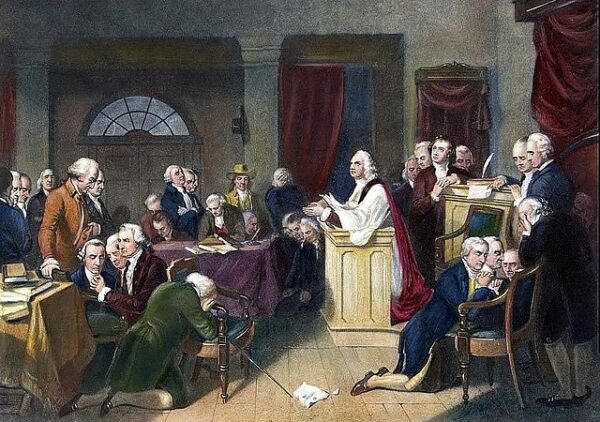

In response, colonial leaders decided to convene a congress to discuss their collective grievances and to coordinate their actions. This meeting brought together 56 delegates from twelve of the thirteen colonies; only Georgia did not send representatives. Among the attendees were some of the most prominent figures of the time, including George Washington, John Adams, Samuel Adams, Patrick Henry, and John Jay. These men, though representing diverse regions and interests, shared a common goal: to seek redress from Britain while maintaining the rights and liberties they believed were being systematically eroded.

The First Continental Congress was held in Carpenter’s Hall, a modest but functional building in the heart of Philadelphia. Over the course of several weeks, the delegates engaged in intense debates and discussions, grappling with the best course of action. While there was no consensus on declaring independence—indeed, most delegates were not yet ready to break with Britain—there was a shared determination to stand up against what they saw as overreach by the British Parliament.

One of the most significant outcomes of the First Continental Congress was the creation of the Continental Association, an agreement among the colonies to impose an economic boycott on British goods. This was intended to pressure Britain by cutting off its American markets, a move that the delegates hoped would force the repeal of the Intolerable Acts. The Congress also agreed to a petition to King George III, outlining their grievances and asking for a peaceful resolution.

In addition to these measures, the Congress set a precedent for future collective action by the colonies. They agreed to reconvene if their efforts to resolve the conflict peacefully were unsuccessful, laying the groundwork for what would eventually become the Second Continental Congress and, ultimately, the Declaration of Independence.

The First Continental Congress marked a crucuial step in the colonies’ path toward unity and resistance against British rule. While it stopped short of outright rebellion, it represented a significant shift in colonial attitudes and set the stage for the events that would lead to the American Revolution. The decisions made in Philadelphia in 1774 underscored the growing resolve among the colonies to defend their rights and assert their place in the broader British Empire, foreshadowing the more radical actions that would soon follow.