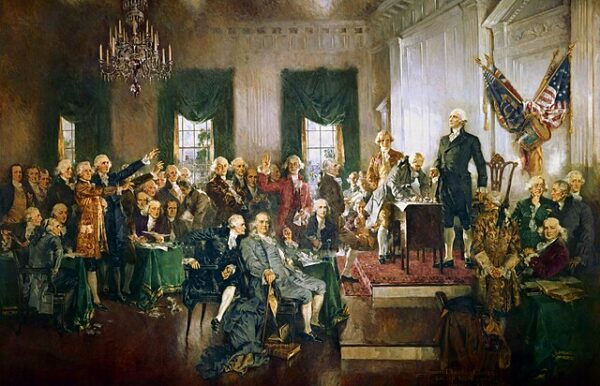

On September 17, 1787, within the revered walls of Independence Hall in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, leaders finished the work of creating what’s been called the greatest government ever devised. After several months of intense deliberation, the framers of the United States Constitution signed a document that would profoundly shape the future of the nation.

The path to the signing was fraught with challenges. The delegates at the convention were among the most distinguished figures of their time, including George Washington, who presided over the proceedings; James Madison, often referred to as the “Father of the Constitution”; Benjamin Franklin; and Alexander Hamilton. Each of these individuals brought distinct perspectives, regional priorities, and political philosophies, leading to vigorous and sometimes heated debates over the structure and powers of the proposed government.

One of the most contentious issues was the question of representation. Larger states advocated for the Virginia Plan, which called for representation based on population, thereby giving them greater influence in the new government. Smaller states, however, supported the New Jersey Plan, which proposed equal representation for each state, ensuring that their voices would not be drowned out by more populous states. This deadlock was ultimately resolved through the Great Compromise, also known as the Connecticut Compromise, which established a bicameral legislature: proportional representation in the House of Representatives and equal representation in the Senate.

Another crucial debate centered on the distribution of power between the federal government and the states. Delegates wrestled with defining the scope of federal authority while preserving the autonomy of the states. This debate gave rise to the principle of federalism, a cornerstone of the Constitution, which divided powers between the national government and the states, allowing for both unity and diversity within the union.

The issue of slavery also cast a shadow over the convention. Although many delegates, particularly those from northern states, opposed the institution, they were unable to reach a consensus on its abolition. Instead, they forged a series of compromises, such as the Three-Fifths Compromise, which stipulated that three-fifths of the enslaved population would be counted for both taxation and representation. The Constitution also allowed the continuation of the transatlantic slave trade until 1808, after which Congress was permitted to ban it. These compromises were necessary to secure the support of southern states but also set the stage for future conflicts that would culminate in the Civil War.

As the final draft of the Constitution neared completion, it became apparent that not all delegates were fully satisfied with the document. Some, like George Mason of Virginia, refused to sign it, citing the absence of a Bill of Rights to protect individual liberties. Others were concerned about the potential for the new government to become overly powerful. Nonetheless, the majority of delegates recognized that the Constitution, while imperfect, represented a significant improvement over the Articles of Confederation and was the best possible compromise given the diverse interests at play.

On the morning of September 17, thirty-nine delegates signed the Constitution, officially bringing the Constitutional Convention to a close. George Washington, as president of the convention, was the first to sign, followed by delegates from twelve of the thirteen states. Rhode Island, which had not sent representatives to the convention, did not participate in the signing.

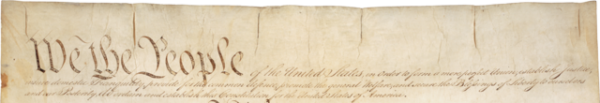

The Constitution then moved to the states for ratification, igniting a fierce debate between Federalists, who supported the new framework, and Anti-Federalists, who feared it would undermine state sovereignty and individual rights. Ultimately, the promise of adding a Bill of Rights helped secure the Constitution’s ratification, and it officially took effect on March 4, 1789.

The signing of the United States Constitution at Independence Hall was a landmark event in world history. It signified the creation of a government founded on the principles of democracy, federalism, and the rule of law. More than two centuries later, the Constitution remains the foundation of the United States government, a testament to the vision and resolve of the framers who convened in Philadelphia on that momentous day.