On September 22, 1991, the Dead Sea Scrolls were made available to the public for the first time, unleashing a storm of publicity and opening a new chapter in the study of these ancient texts. The decision was made by William A. Moffett, director of the Huntington Library in San Marino, California, which possessed a complete set of photographic negatives of the scrolls. This bold move, praised as “plainly progressive” and likened to “breaking down the Berlin Wall,” granted scholars unrestricted access to the scrolls, overturning decades of secrecy.

The Huntington Library’s announcement made headlines across the country, with front-page stories in The New York Times and the Los Angeles Times. For years, only a select group of scholars had access to the scrolls, leading to criticism about the lack of intellectual freedom and the exclusive control of these vital historical documents. Moffett’s decision was celebrated as a victory for open access and academic equity, allowing previously excluded scholars to study and analyze the scrolls freely.

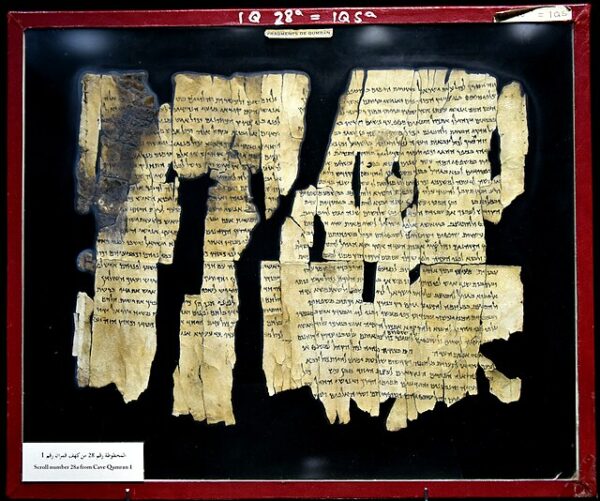

The Dead Sea Scrolls, discovered by Bedouin shepherds between 1947 and 1956 in caves near the Dead Sea, are considered one of the greatest archaeological finds of the 20th century. The scrolls date back to 200 BCE and into the first century CE and include more than 800 manuscripts written in Hebrew and Aramaic. These texts contain some of the earliest known versions of the Hebrew Bible, along with other religious and historical writings that shed light on the social, religious, and political life of early Jewish, Christian, and Islamic traditions.

The Huntington Library’s photographic archive consisted of 3,000 master negatives of the scrolls, meticulously taken by document photographer Robert Schlosser during several trips to Israel beginning in 1980. These images included unpublished manuscripts and materials that had deteriorated in recent years. Schlosser was contracted by Elizabeth Hay Bechtel, founder of the Ancient Biblical Manuscript Center (ABMC) in Claremont, California, to duplicate the Dead Sea Scrolls for preservation and scholarly access.

However, the library’s decision sparked controversy, especially among the exclusive group of scholars who had been working on the scrolls under the control of Israel’s Antiquities Authority. Amir Drori, director of the authority, criticized the move as a breach of contract, arguing that access to the photographs had been granted under the condition that they would not be used without Israeli permission. Despite these objections, many scholars and students without previous access hailed the decision, viewing it as a liberation of knowledge from the grip of the academic elite.

The Dead Sea Scrolls’ release by the Huntington Library brought unprecedented access to these ancient texts, providing scholars around the world with the opportunity to study, analyze, and interpret them. It also ignited a broader conversation about intellectual freedom, the ethics of academic exclusivity, and the importance of making historical treasures available to all. This groundbreaking moment transformed the study of the Dead Sea Scrolls and laid the foundation for future digital and open-access initiatives, ensuring that the scrolls remain a source of learning and discovery for generations to come.