On September 27, 1777, Lancaster, Pennsylvania, for one day, served as the capital of the United States after Congress fled Philadelphia due to the advancing British army.

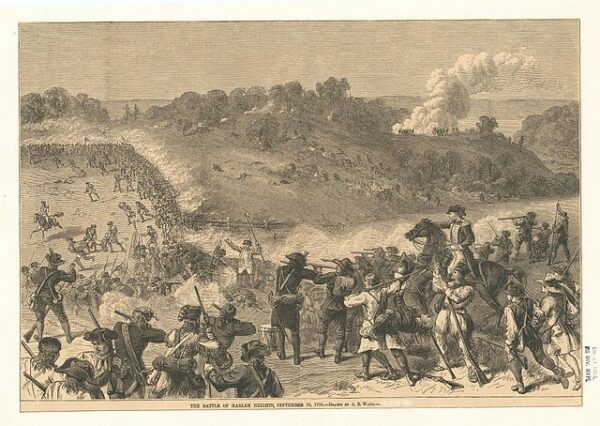

The British had set their sights on Philadelphia, then the largest city in the colonies and home to the Continental Congress. Following a series of defeats, including the Battle of Brandywine earlier in September, General George Washington’s forces were unable to stop the British from moving closer to Philadelphia. With the city’s fall imminent, Congress made the decision to evacuate on September 18, 1777. It was clear that staying in Philadelphia would not only endanger Congress members but also potentially allow the British to take control of the legislative body.

The journey to safety brought Congress to Lancaster, a small, rural town west of Philadelphia. Lancaster had a population of just over 3,000 people at the time, and its location, further inland and away from major battle zones, made it a practical option for Congress’s relocation. Lancaster was already notable for being the largest inland town in America, and its relative security made it a sensible temporary refuge.

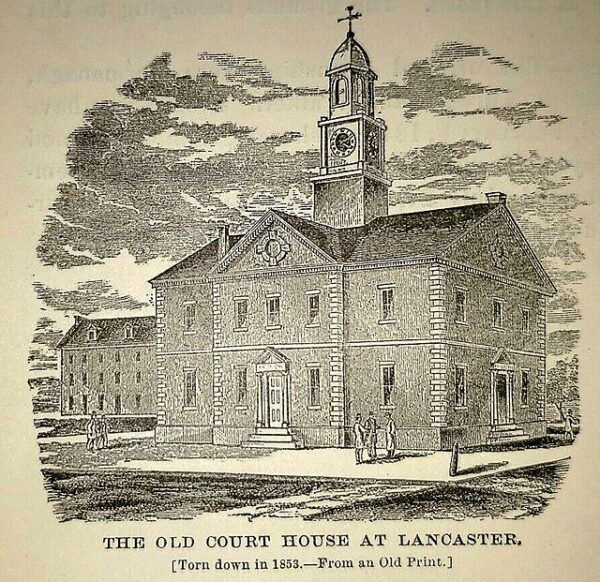

On September 27, Congress convened in Lancaster’s courthouse, transforming the town into the official capital of the fledgling United States for one day. The session was marked by urgency and concern, as members of Congress needed to make swift decisions in light of the war. With Philadelphia under threat and Washington’s army struggling, there was little time to conduct extensive business. While there, Congress continued to deliberate on military strategy and made plans for the future, but they quickly recognized that Lancaster, though a safe location for the moment, was not an ideal long-term capital.

The next day, on September 28, Congress once again moved—this time to York, Pennsylvania, about 25 miles further west. York became the seat of government for the next nine months, as the war continued and Washington’s forces fought to regain control of key territories. During its time in York, Congress adopted several important measures, including approving the Articles of Confederation, which laid the groundwork for the nation’s first governing document.

The single day Lancaster served as the nation’s capital is largely symbolic, but it reflects the extreme measures the Continental Congress had to take to avoid capture and ensure the continuation of the revolutionary cause. Lancaster’s brief role in this chapter of American history highlights the constant danger and uncertainty facing the leaders of the Revolution. It also illustrates the importance of smaller, inland towns like Lancaster and York, which offered safe havens during the most perilous moments of the war.

Today, Lancaster remains a vibrant city with a rich history. While its role as the capital of the United States was fleeting, that one day in 1777 has left an indelible mark on the town’s historical narrative. Lancaster’s contribution to the Revolutionary War effort went beyond hosting Congress for a day—it also supplied the Continental Army with resources and manpower throughout the conflict. The city’s location in a predominantly agricultural region made it an important supplier of food and other materials for Washington’s troops.

Though often overshadowed by the more prominent cities of the Revolution, such as Philadelphia and Boston, Lancaster’s moment as the nation’s capital offers a fascinating glimpse into the practical challenges of running a government during wartime. The rapid evacuation of Congress from Philadelphia and its brief stay in Lancaster are reminders of how precarious the American cause was at times, and how the fate of the nation often rested on swift decisions and temporary solutions.

In modern Lancaster, historical markers commemorate the town’s day as the capital, preserving its unique place in American history. This small Pennsylvania town’s brief time in the spotlight is a testament to the flexibility and resilience of the early United States as it fought for independence.