Al Capone, one of the most notorious gangsters in American history, was convicted of tax evasion on October 17, 1931, marking the fall of a man who had built a criminal empire in Chicago. While Capone was involved in numerous illegal activities, including bootlegging, gambling, and prostitution, it was his failure to pay taxes that led to his downfall. The conviction was a significant victory for the federal government, which had struggled for years to hold Capone accountable for his more violent and visible crimes, such as orchestrating the St. Valentine’s Day Massacre in 1929.

Capone rose to power during the Prohibition Era when the sale and distribution of alcohol were illegal in the United States. He capitalized on the law’s unpopularity, running a bootlegging operation that made him a multimillionaire. By the late 1920s, Capone had become the de facto ruler of the Chicago underworld, controlling speakeasies, brothels, and gambling dens, and exerting influence over corrupt politicians and law enforcement. His public image, however, was one of a charitable man, as he frequently made donations to the poor and opened soup kitchens during the Great Depression. Despite his outward generosity, Capone was also responsible for numerous acts of violence, often using brutality to eliminate rivals and maintain control over his territory.

The federal government, frustrated by their inability to convict Capone on charges related to his violent crimes, turned to a different approach: his finances. The Bureau of Investigation (the FBI) worked closely with the Internal Revenue Service to build a case against Capone for tax evasion. The strategy was based on the premise that even though Capone earned millions through illegal enterprises, he had failed to report any of his income to the federal government, thus evading taxes.

Investigators painstakingly compiled evidence, following the money trail left by Capone’s criminal operations. They tracked payments made to him and his lavish lifestyle, including luxury homes, expensive cars, and extravagant parties, none of which had been accounted for in his tax filings. The case eventually came together, and in 1931, Capone was charged with 22 counts of tax evasion. Initially, Capone attempted to negotiate a plea deal, offering to pay a significant portion of his back taxes and serve a short sentence in exchange for leniency. However, the federal prosecutors refused, determined to make an example of Capone.

The trial began in the fall of 1931, and Capone, confident in his ability to buy his way out of legal trouble, believed he would walk free. His arrogance, however, proved to be his undoing. The judge in the case swapped out the jury on the first day of the trial to prevent any attempts at bribery or intimidation, ensuring a fair verdict. On October 17, 1931, Capone was found guilty of five counts of tax evasion and sentenced to 11 years in federal prison. He was also fined $50,000 and ordered to pay court costs.

Capone’s conviction was a landmark moment in the fight against organized crime in the United States. It demonstrated the effectiveness of using financial crimes to target powerful criminals who had previously evaded justice for their more violent offenses. Capone’s downfall also exposed the limitations of law enforcement at the time, as traditional methods had proven ineffective in stopping his reign of terror.

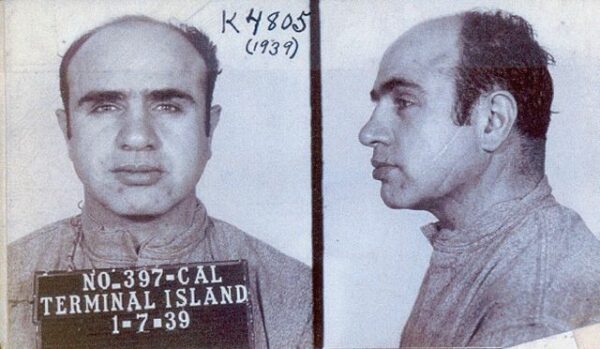

Capone served his sentence at several prisons, including the infamous Alcatraz, where his health rapidly deteriorated due to syphilis. He was released from prison in 1939 and spent the rest of his life in seclusion. He died in 1947, a shadow of the powerful mob boss he had once been.