The Wilmington Insurrection of 1898, often referred to as the Wilmington Race Riot, is a pivotal but often overlooked chapter in American history. It stands as the only instance of a municipal government being forcibly overthrown in the United States. On November 10, 1898, a mob of white supremacists in Wilmington, North Carolina, orchestrated a violent coup d’état, effectively ending the biracial government that had been democratically elected and instigating a reign of terror that forever altered the city and its community.

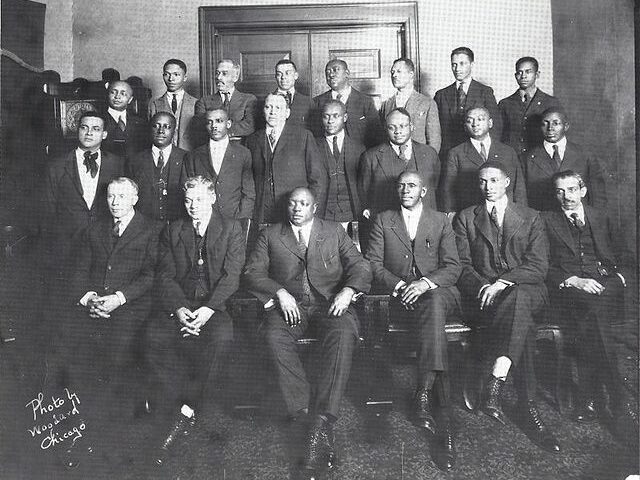

The roots of the insurrection trace back to the post-Reconstruction era when Wilmington was a prosperous, racially integrated city with a thriving Black middle class. Black citizens held significant political power, owning businesses and participating in the local government, alongside their white neighbors. This political and economic autonomy among Black residents fostered resentment among certain white citizens, particularly among influential Democrats who viewed the growing power of Black citizens as a threat to their social and political dominance. White supremacist groups, like the Red Shirts, stoked this resentment, spreading fear and inciting racial animosity.

Tensions in Wilmington were inflamed by the success of the Fusionist movement, a coalition of Black Republicans and white Populists who had managed to secure political power in North Carolina. This coalition angered conservative white Democrats, who sought to regain control of the state. In response, they planned to reclaim Wilmington as part of a broader white supremacy campaign to restore their political power and disenfranchise Black citizens. Propaganda played a vital role, with newspapers like the News and Observer spreading inflammatory, racist editorials that accused Black men of threatening white women’s safety, a common but baseless fear used to justify violent actions against Black communities.

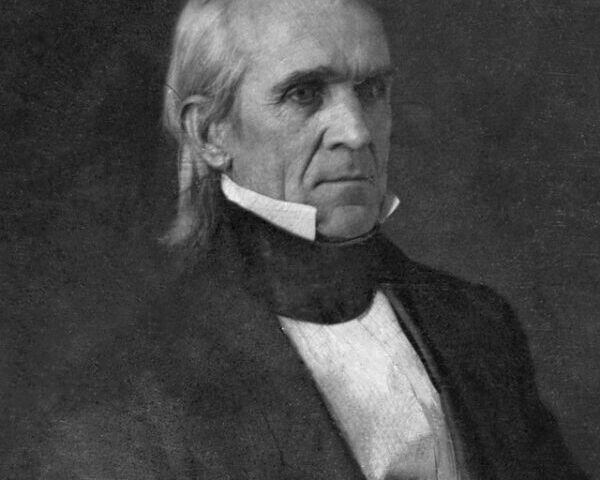

In the months leading up to November 10, prominent white leaders, including Alfred M. Waddell, a former Confederate officer, organized an armed mob, threatening to rid Wilmington of Black influence. Waddell and his associates devised what they called the “White Declaration of Independence,” which demanded that Black residents and officials relinquish their jobs and leave the city. The declaration also targeted Alexander Manly, the editor of the Daily Record, a Black-owned newspaper. Manly had published an editorial challenging white supremacist ideas about interracial relationships, further igniting white rage. Despite repeated threats, Manly refused to abandon his paper or his stance, and this defiance became a rallying point for the mob.

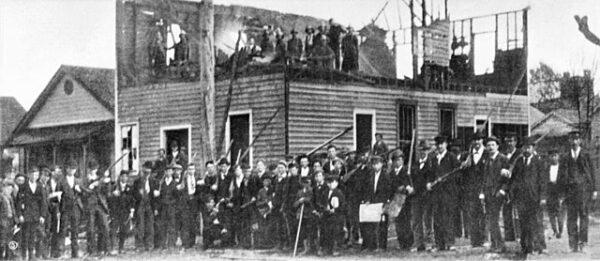

On the morning of November 10, the white mob began its assault by setting fire to the offices of the Daily Record, reducing it to ashes. Violence quickly spread across Wilmington as armed mobs roamed the streets, killing Black citizens and forcing many to flee their homes. Black neighborhoods were terrorized, with men, women, and children targeted in the violence. By the end of the insurrection, an estimated 60 to 300 Black residents had been killed, though exact numbers remain unknown. Many survivors were forced to flee Wilmington permanently, abandoning homes and businesses that were later seized by white residents.

After asserting control through violence, the mob overthrew the city’s duly elected government. Waddell and other white leaders installed themselves in positions of power, forcibly removing Black officials and Fusionist politicians. With Black citizens effectively disenfranchised, Wilmington’s new government implemented policies that further eroded Black rights and established a segregationist structure that would endure for decades.

The Wilmington Insurrection had lasting repercussions. It marked the beginning of a widespread campaign to disenfranchise Black voters across North Carolina and the South, leading to the Jim Crow era. It set a precedent for using violence and intimidation to maintain white supremacy in the political and social spheres. For decades, the events were mischaracterized as a “race riot,” obscuring the deliberate, organized nature of the coup. Only in recent years has the insurrection been recognized as an act of domestic terrorism and a violent seizure of power.