On November 11, 1923, German authorities arrested Adolf Hitler following the Beer Hall Putsch, marking a pivotal event that could have shifted the direction of world history and changed the lives of tens of millions.

The Beer Hall Putsch, which occurred on November 8-9, 1923, was an attempted coup d’état led by Hitler and the National Socialist German Workers’ Party (NSDAP) in Munich. The putsch aimed to overthrow the Weimar Republic and establish a national socialist government in its place. However, the rebellion was swiftly crushed by the Bavarian authorities and the German army.

On the night of November 8, Hitler and his followers marched to the Bürgerbräukeller beer hall, where they confronted police forces. The next day, as the coup collapsed, Hitler and several of his associates were arrested. Hitler was charged with treason, a serious offense that could lead to severe consequences. His trial became a platform for him to gain national attention and spread his extremist ideology.

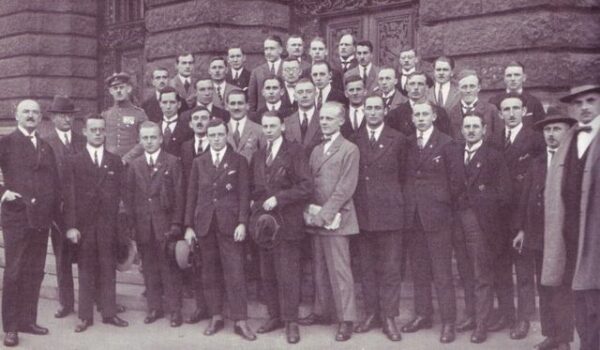

During the trial, Hitler used the courtroom as a platform to present his political ideas and denounce the Weimar Republic. A five-judge panel chaired by Georg Neithardt presided over the trial of Hitler and the other putsch leaders in March 1924.

Like the majority of judges during the Weimar period, Neithardt tended, in cases of high treason, to show leniency towards right-wing defendants who claimed to have acted out of sincere, patriotic motives. Wearing his Iron Cross, awarded for bravery during World War I, Hitler held forth against the Weimar Republic. He claimed the federal government in Berlin had betrayed Germany by signing the Versailles Treaty. He also justified his actions by suggesting that there was a clear and imminent communist threat to Germany, explains the Holocaust Encyclopedia.

The judges convicted Hitler on the charge of high treason. However, they gave him the lightest allowable sentence of five years in a minimum security prison at Landsberg am Lech with the possibility of parole. He was released in December 1924. While Hitler did have a base of support, left and right-wing newspapers criticized the leniency of his sentence. A prominent legal professor also published a paper outlining many of the trial’s worst errors. Bavarian government officials were equally displeased. However, they acted with restraint to avoid giving the impression of trying to influence the affairs of the Bavarian Justice Ministry.

Hitler led a pleasant lifestyle for an inmate. Prison authorities allowed him to wear his civilian clothes, to meet with other inmates as he pleased, and to send and receive many letters. Prison authorities also permitted Hitler to use the services of his personal secretary, Rudolf Hess, a fellow inmate convicted of high treason. While in prison, Hitler dictated to Hess the first volume of his infamous autobiography, Mein Kampf.

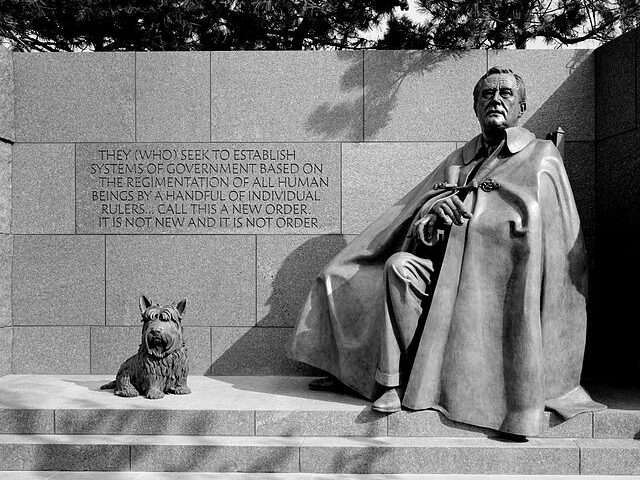

Hitler’s arrest and subsequent trial did not deter his ambitions; instead, they provided him with a platform to garner support and publicity. The Beer Hall Putsch’s failure and Hitler’s imprisonment were temporary setbacks that ultimately contributed to his rise to power. The trial showcased Hitler’s ability to manipulate the legal system and exploit political unrest, foreshadowing the darker chapters in German and world history that would unfold in the years to come.