On November 24, 1832, South Carolina’s state legislature took a dramatic and unprecedented step in American history by passing the Ordinance of Nullification. The ordinance declared that the federal Tariffs of 1828 and 1832 were unconstitutional and, therefore, null and void within the state’s borders. This bold defiance of federal authority set the stage for the Nullification Crisis, a confrontation that tested the limits of state sovereignty and the federal government’s authority under the Constitution.

The roots of the crisis lay in the Tariff of 1828, also known as the “Tariff of Abominations,” and its successor, the Tariff of 1832. These tariffs imposed high duties on imported goods, protecting northern manufacturers at the expense of southern agricultural economies. South Carolina, dominated by a plantation economy reliant on foreign trade, suffered economically under these measures. Many South Carolinians viewed the tariffs as an unfair and unconstitutional overreach by the federal government, disproportionately favoring one region over another.

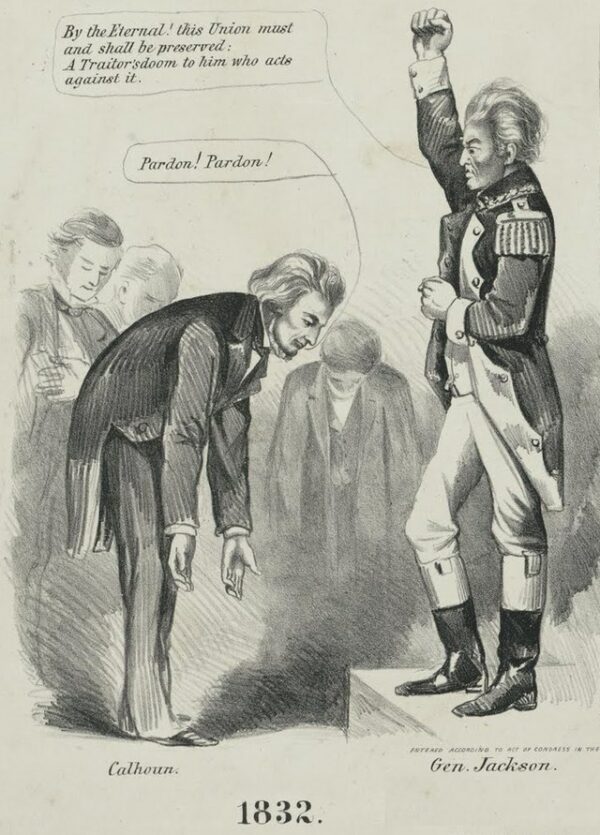

Leading the charge against these tariffs was Vice President John C. Calhoun, a South Carolinian who became the intellectual architect of the nullification doctrine. Calhoun argued that the U.S. Constitution was a compact among sovereign states, and if the federal government exceeded its constitutional authority, states had the right to nullify federal laws within their borders. This doctrine drew from earlier states’ rights arguments, including those expressed in the Virginia and Kentucky Resolutions of 1798.

South Carolina’s discontent came to a head in 1832. Although the Tariff of 1832 reduced some rates, it failed to address the core grievances of the South. Feeling ignored and marginalized, South Carolina’s legislature convened a state convention to address the issue. The result was the Ordinance of Nullification, which stated that the tariffs were “unauthorized by the Constitution of the United States” and would not be enforced in South Carolina. The ordinance also threatened secession if the federal government attempted to enforce the tariffs.

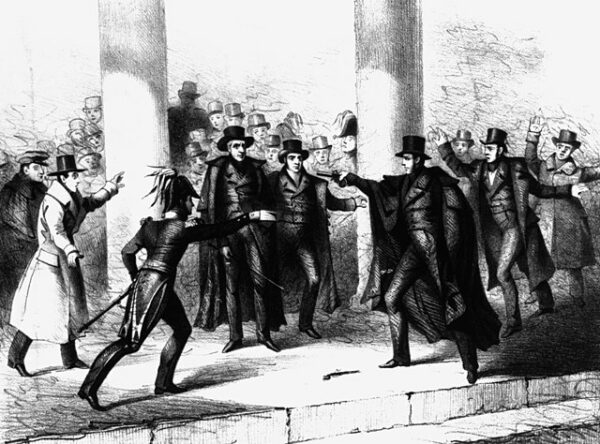

President Andrew Jackson, a staunch unionist, responded decisively to South Carolina’s challenge. While he sympathized with southern concerns about the tariffs, he believed in the supremacy of federal law and the indivisibility of the Union. Jackson issued a proclamation condemning nullification as an act of treason, asserting that no state had the right to unilaterally invalidate federal law.

Jackson also sought congressional approval for the Force Bill, which authorized him to use military action to ensure compliance with federal laws. At the same time, Jackson worked with Congress to pass a compromise tariff, drafted by Senator Henry Clay, which gradually reduced tariff rates over the next decade. This dual approach of firmness and compromise proved effective.

South Carolina, facing the prospect of military intervention and isolated without support from other southern states, repealed the Ordinance of Nullification in 1833. However, the state simultaneously nullified the Force Bill as a symbolic gesture of defiance, ensuring that its principles were not entirely abandoned.

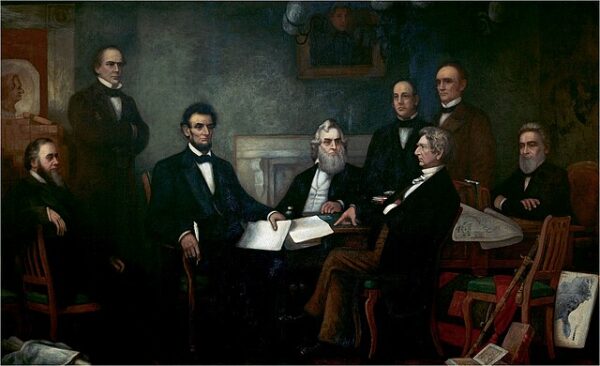

The Nullification Crisis had far-reaching consequences. It highlighted the deepening sectional tensions between the North and South, foreshadowing the conflicts that would eventually culminate in the Civil War. It also demonstrated the precarious balance between states’ rights and federal authority, a debate that would continue to shape American politics.

For Andrew Jackson, the crisis affirmed his reputation as a strong leader willing to defend the Union at all costs, but it also revealed the growing radicalism of the proslavery movement.