On December 14, 1836, the long-running Toledo War—a peculiar and bloodless boundary conflict between Michigan Territory and Ohio—reached its unofficial end when Michigan delegates convened at the so-called “Frostbitten Convention.” They voted to accept Congress’ proposed terms for statehood, closing a contentious chapter in American history and paving the way for Michigan to join the Union as the 26th state.

The dispute centered on the Toledo Strip, a slender piece of land along the Michigan-Ohio border. This strip, which included the city of Toledo, held great strategic value due to its potential as a transportation and trade hub. The controversy stemmed from differing interpretations of the 1787 Northwest Ordinance and the 1802 Enabling Act, which outlined territorial boundaries.

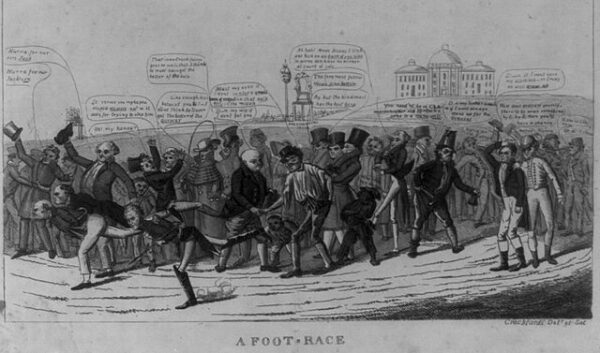

By 1835, tensions boiled over. Michigan, still a territory, enacted legislation claiming the Toledo Strip and began mobilizing militias to defend its claim. Ohio, already a state, responded in kind. While the conflict never escalated into bloodshed, the aggressive posturing and minor skirmishes strained relations between the two regions and delayed Michigan’s efforts to attain statehood.

The federal government eventually stepped in, proposing a compromise to settle the dispute. Ohio would keep the Toledo Strip, while Michigan would gain a significant portion of the Upper Peninsula as compensation. Michigan’s territorial leaders initially rejected the deal, viewing the Upper Peninsula—heavily forested and sparsely populated—as an unfavorable exchange for the economically promising Toledo Strip.

However, Michigan’s financial troubles soon forced a reevaluation. The prolonged standoff had drained territorial resources, and the economic challenges of governance without statehood added to the strain. With these pressures mounting, Michigan’s leaders called a second constitutional convention to reconsider Congress’ terms. Held in December amid brutal winter conditions, this meeting came to be known as the “Frostbitten Convention.”

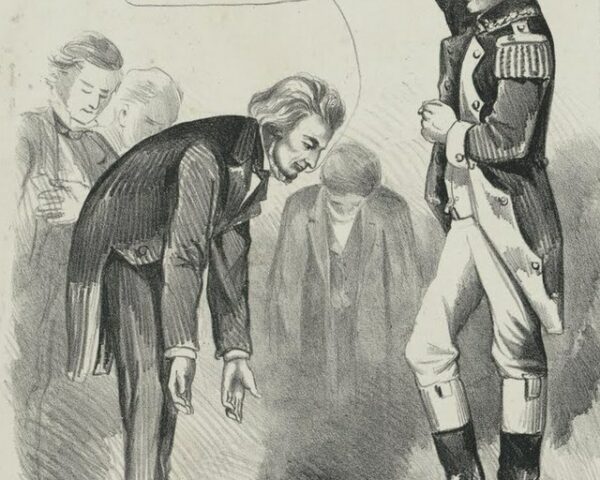

On December 14, 1836, 49 delegates assembled in Ann Arbor. The atmosphere was charged, with many attendees and citizens still bitterly opposed to surrendering the Toledo Strip. After heated debate, the delegates voted to accept the compromise. While the decision was far from unanimous, it reflected the growing recognition that statehood—and the benefits it would bring—outweighed the cost of continuing the dispute.

This pivotal vote cleared the way for Michigan’s admission to the Union. On January 26, 1837, President Andrew Jackson signed the bill that officially granted Michigan statehood. Ironically, the Upper Peninsula, initially dismissed as a poor consolation prize, would later prove to be a major asset, rich with valuable mineral deposits like iron and copper.