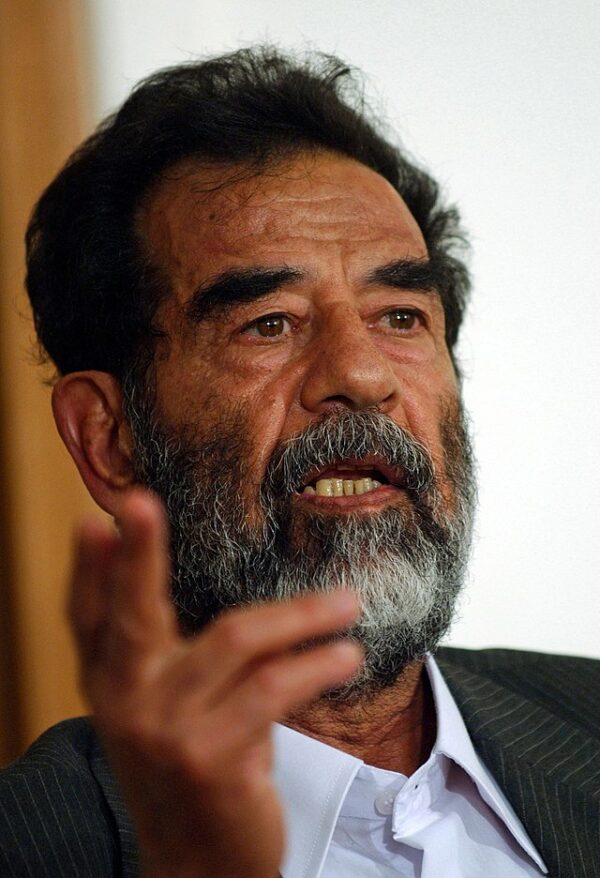

On December 30, 2006, Saddam Hussein, the former President of Iraq, was executed by hanging after being convicted of crimes against humanity. This event marked the end of a turbulent era in Iraq’s history and symbolized the fall of a regime that ruled the country with authoritarian control for over two decades. The execution, carried out at dawn in Baghdad, followed the Iraqi appeals court’s decision to uphold his death sentence just days earlier.

Saddam Hussein had been captured on December 13, 2003, near his hometown of Tikrit by U.S. forces after months of pursuit following the U.S.-led invasion of Iraq in March 2003. After his capture, Saddam was handed over to Iraqi authorities and put on trial for his role in the 1982 Dujail massacre, where 148 Shiite Muslims were killed in retaliation for an assassination attempt against him. The trial, which began in October 2005, was marred by allegations of bias, political interference, and irregularities. Saddam himself frequently disrupted proceedings, rejecting the court’s authority and declaring himself the rightful leader of Iraq. Despite these controversies, the Iraqi High Tribunal found him guilty on November 5, 2006, sentencing him to death.

In the early hours of December 30, 2006, Saddam was executed at a secret location in Baghdad. Graphic footage of the event, including guards taunting him with sectarian insults, was leaked to the public, sparking global criticism over the conduct of the execution. While many Iraqis—particularly Shiites and Kurds who suffered under his regime—celebrated his death as justice served, others, especially within Iraq’s Sunni minority, viewed the execution as an act of political vengeance rather than impartial justice. Globally, reactions were mixed. U.S. President George W. Bush called it a key milestone in Iraq’s democratic journey, while human rights organizations, such as Amnesty International, criticized the trial and execution as deeply flawed.

Saddam Hussein’s legacy remains profoundly divisive. During his presidency from 1979 to 2003, he maintained power through fear, propaganda, and brutal repression. His rule included notorious atrocities such as the genocidal Anfal campaign against the Kurds, the chemical attack on Halabja, and the suppression of Shiite uprisings after the Gulf War in 1991. However, some Iraqis remember his early years in power as a time of economic stability and infrastructure growth fueled by Iraq’s oil wealth. Despite these developments, his aggressive foreign policies—including the Iran-Iraq War in 1980 and the invasion of Kuwait in 1990—plunged Iraq into devastating conflicts, international sanctions, and widespread suffering.

The execution of Saddam Hussein did not resolve Iraq’s deeper issues. Instead, the country spiraled into sectarian violence, political instability, and insurgency, worsened by the U.S.-led occupation and the power vacuum left by Saddam’s removal. Extremist groups like Al-Qaeda in Iraq and, later, ISIS emerged, capitalizing on the fragile state of post-Saddam Iraq. For many, Saddam’s death represented both an end to a brutal chapter and the beginning of new, uncertain challenges.

Nearly two decades later, Iraq continues to grapple with the enduring effects of Saddam Hussein’s rule. His execution remains a symbolic moment in modern Middle Eastern history—viewed by some as a step toward justice and by others as an act of revenge. The shadow of his authoritarian rule still looms over Iraq’s political and social fabric, shaping the nation’s ongoing struggle for stability and unity.