The Mud March of February 9, 1907, was the first large-scale demonstration organized by the National Union of Women’s Suffrage Societies (NUWSS) and marked a crucial moment in the fight for women’s voting rights in Britain. While not the first suffrage protest, its unprecedented size and visibility set the stage for future mass mobilizations. The march earned its name from the freezing rain and thick mud that turned London’s streets into a quagmire, reflecting both the physical and political obstacles suffragists faced in their struggle for enfranchisement.

Founded in 1897 by Millicent Fawcett, the NUWSS represented the non-militant wing of the suffrage movement. Unlike the more radical Women’s Social and Political Union (WSPU)—led by Emmeline and Christabel Pankhurst, who advocated civil disobedience—the NUWSS relied on legal and constitutional methods, including petitions, lobbying, and peaceful demonstrations. The Mud March was a deliberate attempt to generate public sympathy and political pressure without resorting to militant tactics that might alienate influential supporters.

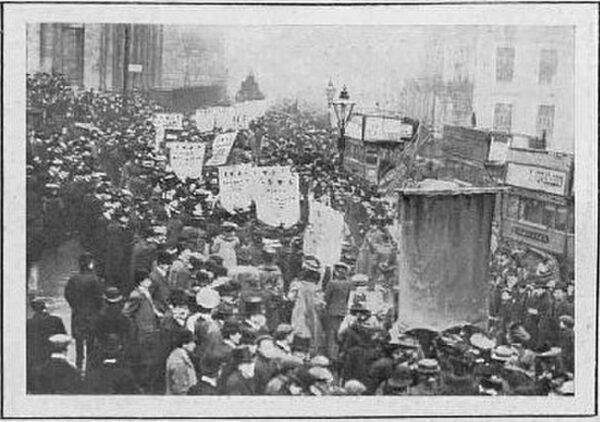

On the morning of February 9, 1907, more than 3,000 women gathered in Hyde Park, braving relentless rain and ankle-deep mud to march to Exeter Hall. Dressed in long skirts and heavy cloaks, they carried umbrellas and banners, many of which drooped under the weight of the rain. Their ranks included women from all walks of life, from aristocrats and professionals to factory workers and trade unionists. Among the notable figures marching that day were Lady Frances Balfour, a prominent suffrage advocate from the aristocracy, and Dr. Elizabeth Garrett Anderson, Britain’s first female doctor. The inclusion of students, teachers, and labor activists underscored the broad support for women’s suffrage. This diverse representation was a strategic move by the NUWSS to dispel the notion that suffrage was merely the demand of a radical fringe. Instead, the march illustrated that women from all social backgrounds supported the right to vote. Banners bearing messages such as “Votes for Women” and “Law-Abiding Suffragists” reinforced their moderate stance.

Despite the miserable weather, the march attracted widespread attention. Onlookers lined the streets, their reactions ranging from ridicule to admiration. While some dismissed the demonstrators as a foolish spectacle, others were moved by their determination. The event also captured the attention of the press. Though newspapers like The Times were often skeptical of the suffrage movement, they acknowledged the discipline and dignity of the march. For many Londoners, it was their first time seeing suffragists as organized, resolute, and respectable women, rather than the unruly caricatures often depicted in the media.

At the end of the march, the women gathered at Exeter Hall, where leading suffragists, including Millicent Fawcett, delivered powerful speeches. Fawcett emphasized the movement’s commitment to peaceful protest and reasoned debate, urging politicians to take their demands seriously. While the government did not immediately respond, the event proved that mass demonstrations could influence public opinion and put pressure on political leaders.

In the years that followed, the NUWSS continued organizing processions, petitions, and lobbying efforts, culminating in the 1913 Women’s Suffrage Pilgrimage, which mobilized tens of thousands across Britain. Although the WSPU’s militant actions often dominated headlines, the NUWSS’s persistent legal advocacy played a crucial role in shifting attitudes and ultimately securing women’s right to vote.