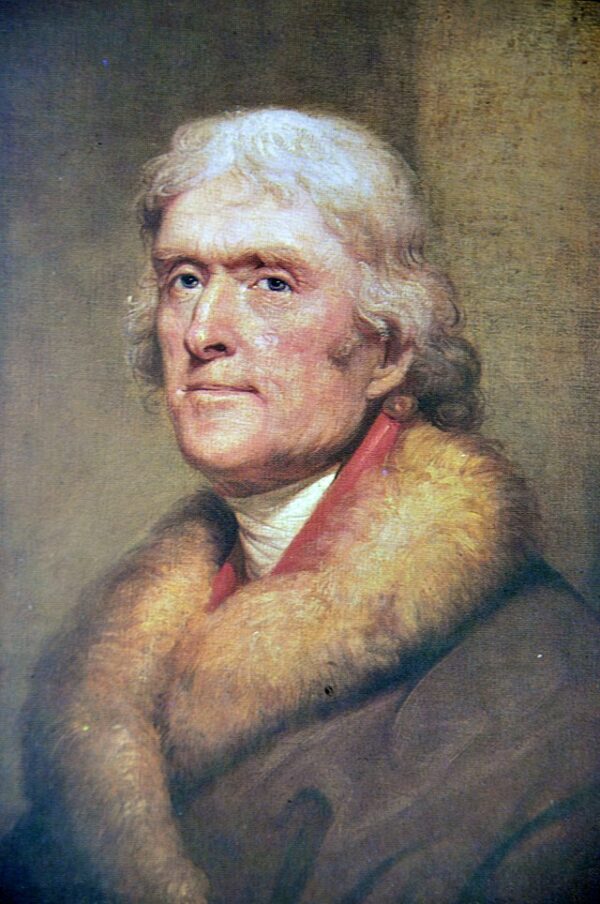

The presidential election of 1800 was one of the most pivotal and contentious moments in American political history, revealing both the strengths and weaknesses of the nation’s young electoral system. The contest between Thomas Jefferson and Aaron Burr, both representing the Democratic-Republican Party, resulted in an unprecedented constitutional crisis when the Electoral College produced a tie, forcing an extraordinary resolution by the House of Representatives.

Often referred to as the “Revolution of 1800,” this election was a bitter struggle between the incumbent Federalist president, John Adams, and his Democratic-Republican challenger, Thomas Jefferson. The political landscape was deeply divided. Federalists, led by Adams and Alexander Hamilton, supported a strong central government and close economic ties with Britain, while Democratic-Republicans, led by Jefferson and James Madison, advocated for states’ rights, an agrarian-based economy, and stronger relations with France. The campaign was marked by intense political rhetoric, accusations of tyranny, and stark ideological divisions between the two emerging political parties.

At the time, the U.S. Constitution’s original framework for presidential elections required electors in the Electoral College to cast two votes without distinguishing between their first and second choices. The candidate with the most votes would become president, while the runner-up would serve as vice president. This system, created before the rise of political parties, proved highly problematic in 1800. Democratic-Republicans intended for Jefferson to become president and Burr to serve as vice president by ensuring that one elector would vote differently, preventing a tie. However, due to poor coordination—or possibly Burr’s own ambitions—both candidates received 73 electoral votes, triggering a constitutional crisis.

With the tie, the decision was left to the Federalist-controlled House of Representatives, as outlined in the Constitution. Each state delegation would cast a single vote, and a candidate needed a majority of nine votes to win. Federalists, distrustful of Jefferson, saw an opportunity to block his presidency. Some sought political concessions from Jefferson in exchange for their support, while others, led by Alexander Hamilton—who disliked both candidates but viewed Burr as dangerously unprincipled—urged fellow Federalists to support Jefferson. Meanwhile, a faction of Federalists toyed with backing Burr to prevent Jefferson’s victory.

Voting in the House began on February 11, 1801, but ballot after ballot failed to produce a winner. For six days and 35 rounds of voting, the deadlock persisted. Finally, on February 17, after behind-the-scenes negotiations and Hamilton’s quiet influence, several Federalists abstained or changed their votes, allowing Jefferson to secure victory on the 36th ballot. Burr, who had neither openly campaigned for the presidency nor stepped aside, became vice president.

This crisis exposed serious flaws in the Electoral College system, prompting the passage of the Twelfth Amendment in 1804, which required electors to cast separate votes for president and vice president. It also deepened tensions between Jefferson and Burr, contributing to Burr’s political downfall and culminating in his infamous duel with Hamilton in 1804.

The election of 1800 was a defining moment in American history, testing the resilience of the constitutional system while highlighting its vulnerabilities. It marked the first peaceful transfer of power between opposing political parties, establishing a critical precedent for democratic governance. Jefferson’s victory ushered in a long era of Democratic-Republican dominance, while Burr’s political career never fully recovered, leading him toward a legacy of scandal and controversy.