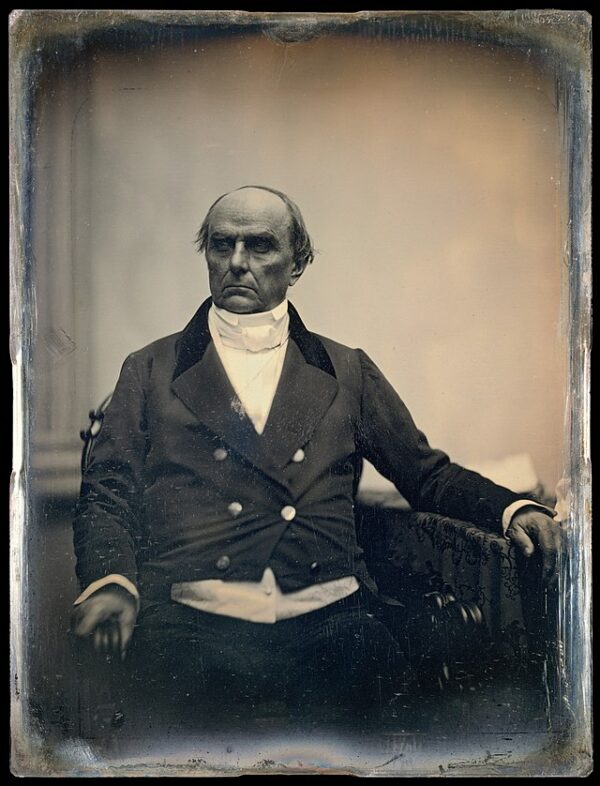

On March 7, 1850, Senator Daniel Webster of Massachusetts delivered one of the most significant speeches in American history, later known as the “Seventh of March” speech. Speaking at a time of deep national division, Webster endorsed the Compromise of 1850, a contentious set of legislative measures aimed at resolving disputes between the North and South over the expansion of slavery into the territories acquired during the Mexican-American War. His speech, an appeal for national unity, became a defining moment in his career, but it also led to his political downfall in New England, where many viewed his stance as a betrayal of the antislavery movement.

Webster was one of the three influential statesmen known as the “Great Triumvirate,” alongside Henry Clay and John C. Calhoun. A lifelong advocate for American nationalism, he prioritized the preservation of the Union above all else. By 1850, however, the country was on the brink of disunion. The proposed admission of California as a free state threatened to upset the delicate balance between free and slave states in the Senate. Meanwhile, Southerners were demanding a stronger fugitive slave law to protect what they saw as their constitutional rights. In response, Clay proposed a compromise: California would enter the Union as a free state, the slave trade (but not slavery itself) would be abolished in Washington, D.C., a stricter Fugitive Slave Act would be enacted, and the question of slavery in the territories of New Mexico and Utah would be left to popular sovereignty.

Although Webster represented a state with strong abolitionist sentiment, he feared that extreme positions on both sides were pushing the nation toward civil war. In his speech, he criticized both Northern radicals and Southern hardliners, arguing that preserving the Union required mutual concessions. He declared, “I wish to speak today not as a Massachusetts man, nor as a Northern man, but as an American,” underscoring his belief that national unity was more important than regional loyalties. He also opposed the Wilmot Proviso, which sought to ban slavery in all newly acquired territories, arguing that slavery would not naturally expand into much of the West due to its climate and geography.

The most controversial part of Webster’s speech was his endorsement of the Fugitive Slave Act. While acknowledging the moral opposition to slavery among Northerners, he insisted that the Constitution required the return of fugitive slaves and that the South had a legitimate grievance over the North’s failure to enforce existing laws. “The South, in my judgment, is right,” he stated, arguing that disregarding the Constitution on this issue undermined the rule of law. His position outraged many of his Northern supporters, especially abolitionists who had once admired him as a defender of liberty. To them, he had abandoned principle in an attempt to appease the South.

Webster’s speech was well received in the South and among moderates who hoped to prevent secession, but it came at a steep political cost. In Massachusetts, abolitionists condemned him, and his support for the Compromise of 1850 effectively ended his national political career. Prominent figures such as Horace Mann labeled him a traitor to the cause of freedom, while poet John Greenleaf Whittier denounced him in verse as a “fallen star.” Rather than solidifying his legacy as a unifier, his speech alienated the emerging generation of antislavery activists who would later form the backbone of the Republican Party.

Despite widespread criticism, Webster never wavered in his belief that he had acted in the nation’s best interest by postponing civil war. In the short term, the Compromise of 1850 did ease sectional tensions, but the Fugitive Slave Act proved to be one of the most divisive laws in American history, further radicalizing the North against slavery rather than placating the South. Webster, who died in 1852, did not live to see the full consequences of his stance. However, his “Seventh of March” speech remains a pivotal moment in U.S. history—a speech that, in attempting to preserve the Union, may have ultimately contributed to the eventual Civil War.