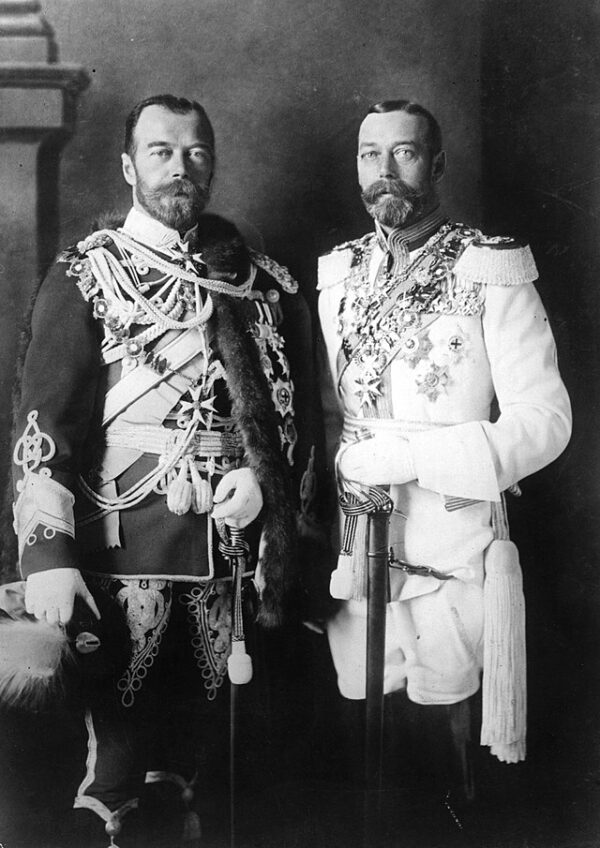

On March 15, 1917 it was all over in Russia as Tsar Nicholas II of Russia abdicated the throne, marking the end of the 304-year reign of the Romanov dynasty. His resignation was the culmination of years of mounting political instability, social unrest, and military failures. The collapse of tsarist autocracy was not solely due to Nicholas II’s personal shortcomings—though his indecisiveness, detachment from political realities, and resistance to reform undoubtedly hastened the monarchy’s downfall. Rather, it was the result of deep-seated structural weaknesses within the Russian Empire, further exacerbated by the enormous strain of World War I.

The immediate trigger for Nicholas II’s abdication was the February Revolution of 1917, a popular uprising that erupted in Petrograd (modern-day St. Petersburg). Discontent had been growing for years, fueled by the humiliating defeat in the Russo-Japanese War (1904–1905), the failed 1905 revolution, and the Tsar’s reluctance to implement substantial constitutional reforms. By 1917, Russia’s involvement in World War I had only deepened the crisis. The war effort was plagued by devastating military defeats, logistical breakdowns, and a severe economic crisis that led to widespread food shortages and soaring inflation. The imperial government’s failure to address these issues eroded public confidence in the monarchy.

By early March 1917, unrest in Petrograd reached a breaking point as factory workers initiated strikes and mass demonstrations, demanding bread and an end to the war. These protests quickly escalated into a full-scale revolt when soldiers of the Petrograd garrison mutinied and joined the demonstrators. As the imperial government lost control of the capital, Nicholas—stationed at military headquarters in Mogilev—ordered troops to suppress the uprising. However, the soldiers in Petrograd defied his orders, and key military leaders advised the Tsar that his position had become untenable.

Under mounting pressure, Nicholas initially considered transferring power to his son, Alexei, under a regency. However, fearing for the child’s health (as Alexei suffered from hemophilia) and recognizing that this move would not resolve the crisis, he ultimately abdicated in favor of his brother, Grand Duke Michael Alexandrovich. Michael, however, refused the throne unless a national assembly approved his rule, effectively bringing the Romanov dynasty to an end.

With the monarchy abolished, a Provisional Government was established under Prince Georgy Lvov and later Alexander Kerensky. Though it aimed to restore order, it struggled to gain legitimacy, particularly among radical socialists and Bolsheviks, who saw it as an extension of the old regime. Nicholas II’s abdication was merely the first stage of the Russian Revolution, paving the way for the Bolshevik seizure of power in October 1917.

For Nicholas and his family, abdication marked the beginning of a tragic final chapter. Initially placed under house arrest, they were later exiled to Siberia and eventually transferred to Yekaterinburg. In July 1918, they were executed by Bolshevik forces, symbolizing not just the fall of the Romanov dynasty but the complete dismantling of Russia’s centuries-old autocratic system.

Historians continue to debate Nicholas II’s legacy. Some view him as an ineffectual ruler who failed to modernize Russia and respond to growing demands for reform. Others argue that he was a victim of historical forces beyond his control. Regardless of perspective, his abdication in 1917 was a defining moment in Russian history—one that set in motion a revolutionary upheaval that would reshape the 20th century.