On March 23, 1933, the German Reichstag passed the Enabling Act (Gesetz zur Behebung der Not von Volk und Reich), granting Adolf Hitler the authority to enact laws without parliamentary approval. Voted into law under immense political pressure and threats of violence, this moment marked the official end of the Weimar Republic and the onset of Nazi dictatorship in Germany.

Just weeks earlier, Hitler had been appointed Chancellor on January 30, 1933. The Enabling Act was framed as a temporary, constitutional solution to Germany’s growing crises. In reality, it gave Hitler’s cabinet sweeping powers to legislate independently—including the ability to override the constitution—without needing the president’s or parliament’s consent. Though it was initially valid for four years, the law was renewed multiple times and became the legal foundation of Hitler’s totalitarian regime.

The political environment surrounding the vote was deliberately chaotic and repressive. After the Reichstag fire on February 27—a blaze the Nazis blamed on Dutch communist Marinus van der Lubbe—President Paul von Hindenburg issued the Reichstag Fire Decree. This emergency order suspended basic civil liberties, including freedom of speech, the press, assembly, and privacy. It also allowed authorities to detain individuals indefinitely without trial. The Nazis quickly used this decree to arrest thousands of political opponents, especially Communists and Social Democrats, and to shut down opposition newspapers.

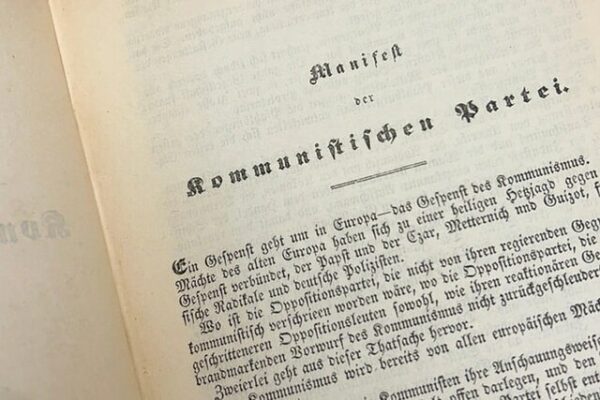

By the time the Reichstag met to vote on the Enabling Act, left-wing representation had been effectively neutralized. The Communist Party (KPD) was banned, and many Social Democratic (SPD) members had been jailed or forced into hiding. The vote took place amid a climate of intimidation, with Nazi paramilitary forces (SA and SS) present in and around the legislative building.

Despite the overwhelming pressure, the SPD, led by Otto Wels, stood as the lone voice of dissent. In a courageous yet ultimately symbolic speech, Wels declared, “Freedom and life can be taken from us, but not our honor.” The Act passed with 444 votes in favor and 94 against—all from the SPD. Conservative parties, including the Centre Party, voted in favor—either in hopes of preserving their influence or out of fear of further unrest.

Once empowered by the Enabling Act, Hitler moved quickly to dismantle all democratic institutions. Independent trade unions were abolished and replaced with the Nazi-controlled German Labor Front. By July 1933, all political parties except the Nazi Party were banned. The country’s federal structure was dismantled, with all state governments brought under Nazi control. By the end of that year, Germany had become a one-party dictatorship with no opposition, no free press, and no independent judiciary.

Although the law had the appearance of legality, the Enabling Act is a striking example of how the Nazis dismantled democracy from within. Hitler did not seize power through a violent coup; instead, he manipulated existing legal structures, exploited public fear, and took advantage of institutional weaknesses. Many conservative leaders, believing they could control him or maintain stability, supported the Act—only to be sidelined as Hitler consolidated total control.

March 23, 1933, remains one of the most pivotal dates in modern history. What followed was not born from revolution, but from a vote—legal in form, devastating in consequence. The Enabling Act did not merely empower Hitler; it dismantled German democracy.