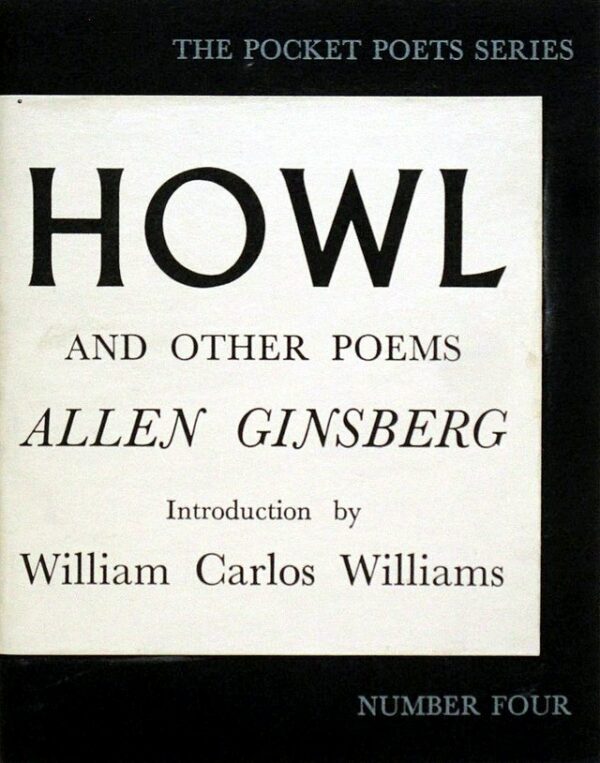

On March 25, 1957, U.S. Customs officials confiscated over 500 copies of Howl and Other Poems by Allen Ginsberg as they arrived in San Francisco from a British printer. What began as a government seizure quickly became one of American literary history’s most important censorship cases. It challenged the boundaries of free expression in postwar America and helped usher in the cultural and legal shifts that would define the 1960s.

Howl and Other Poems, published by City Lights Books—a small press run by poet and bookseller Lawrence Ferlinghetti—was raw and intense. Its famous opening line, “I saw the best minds of my generation destroyed by madness, starving hysterical naked,” voiced a powerful spiritual and emotional protest. Written in a rhythm influenced by jazz and the Beat movement, the poem boldly rejected the industrial conformity, sexual repression, militarism, and capitalism that dominated 1950s American life. These topics were rarely touched in mainstream writing at the time.

The authorities labeled the poem obscene, pointing to its explicit sexual language and its challenge to conventional morality. But the decision to seize the book wasn’t made in isolation—it reflected a wider Cold War atmosphere of fear and suppression. During this era, the U.S. government pushed to defend “traditional values” against what it saw as threats from communism, homosexuality, and dissenting intellectual voices. Howl, which openly embraced homoeroticism and a bohemian lifestyle, became a direct target of this cultural crackdown.

Ferlinghetti, who had ordered the books from a printer in London, was prepared for conflict. He and his attorney, Albert Bendich, quickly prepared a legal defense when the San Francisco district attorney charged Ferlinghetti with publishing and distributing obscene materials. Ginsberg was not charged, as he had left the country for Tangier, but his poem stood at the heart of the courtroom drama.

The case, People v. Ferlinghetti, hinged on whether Howl possessed “redeeming social value,” a new idea becoming central to First Amendment debates. The defense presented scholars, critics, and clergy who all testified that Howl had literary and moral significance. They argued that its graphic language was not meant to shock for shock’s sake, but to convey a deeper message—a protest against a society that stripped people of their humanity.

Though Judge Clayton Horn was a conservative and a practicing Christian, he ruled in favor of Ferlinghetti. He determined that Howl was a serious work of literature and that its language, while controversial, served a greater artistic and social purpose. The decision marked a major turning point in U.S. obscenity law, affirming that the First Amendment protected literature that used explicit or controversial language to explore meaningful themes.

The Howl trial helped solidify the Beat Generation’s cultural status, turning Ginsberg into a literary icon. It also opened the door for other once-banned books like Naked Lunch by William S. Burroughs and Tropic of Cancer by Henry Miller to be published freely.

What began as a routine act of censorship on March 25 became a landmark moment for American cultural freedom. The court’s defense of Howl upheld not only Ginsberg’s right to express difficult ideas, but also the public’s right to read and engage with them. This decision helped shape a more open literary world in the years that followed.