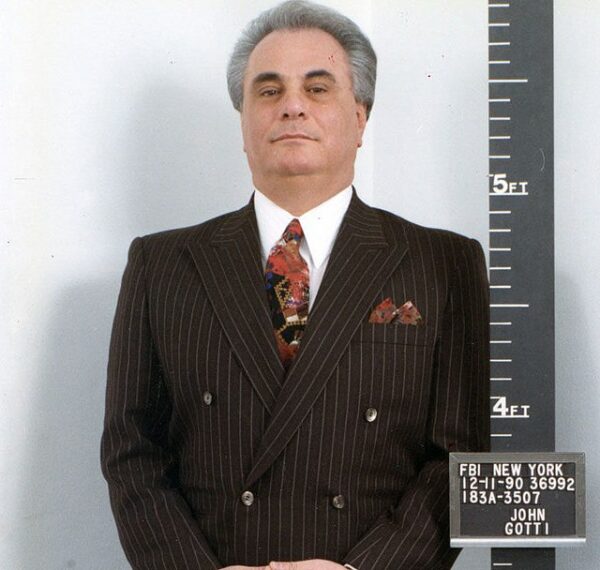

In April 1992, the powerful image of John Gotti—the sharply dressed, seemingly untouchable Mafia boss—was finally shattered. On April 2, a federal jury in Brooklyn convicted Gotti on all charges, including murder, racketeering, obstruction of justice, and tax evasion. The verdict marked a turning point for the Gambino crime family, once the most dominant of New York’s Five Families, and delivered a major blow to organized crime across the country.

Known as the “Teflon Don” for his ability to avoid conviction in earlier trials, Gotti had become a symbol of Mafia invincibility. His flashy style, public confidence, and visible defiance of law enforcement made him both a media sensation and a public face of the American underworld. But the federal government, after years of failed cases, finally found the evidence it needed—thanks to Gotti’s own underboss, Salvatore “Sammy the Bull” Gravano.

Gravano, who faced a long prison sentence himself, agreed to testify for the prosecution. His detailed account of the Mafia’s inner operations—including murder plots, extortion, and Gotti’s direct involvement in violent crimes—was a breakthrough for the case. Gravano’s cooperation was a major win for federal prosecutors and a devastating blow to the Mob’s longstanding code of silence.

A key part of the case centered on Gotti’s role in organizing several murders, especially the 1985 assassination of Gambino boss Paul Castellano outside Manhattan’s Sparks Steak House. That killing, carried out without approval from the Mafia’s ruling body, shocked other crime figures but cleared Gotti’s path to power. Once in charge, he led the family with a mix of brutality and public swagger, favoring high-profile violence and open defiance of authority.

Prosecutors also presented hours of FBI wiretaps, recorded from a hidden device in the upstairs apartment of the Ravenite Social Club—Gotti’s de facto headquarters in Little Italy. The tapes captured Gotti talking about beatings and killings in unambiguous terms. Despite defense efforts to discredit Gravano as self-serving, the recordings spoke for themselves.

The jury deliberated less than two days before reaching a verdict. U.S. District Judge I. Leo Glasser sentenced Gotti to life in prison without parole. The once-smiling Mafia boss, so confident in front of cameras, sat expressionless as the sentence was delivered.

The conviction was both a legal and symbolic triumph for federal law enforcement. It showed that even the most powerful crime figures could be brought down. The case also reflected a broader shift in the government’s approach during the 1980s and ’90s, particularly the use of the RICO Act to target entire criminal organizations by going after their leadership.

Though Gotti’s influence faded in prison, his story continued to capture public attention. He died of cancer in 2002 at a federal medical prison in Missouri. His death marked the end of a notorious chapter in American criminal history.

Still, the 1992 conviction remains the defining moment of his downfall—a dramatic turning point that reminded the nation that even legends of the underworld are not immune to justice.