On April 4, 1841, just one month into his presidency, William Henry Harrison died from what was believed to be pneumonia, becoming the first U.S. president to die in office. His sudden death—only 31 days after delivering the longest inaugural address in American history—shocked the young nation. It also raised urgent constitutional questions and disrupted the fragile political balance of the time. Though often recalled as a historical oddity—an aging president undone by cold weather and poor judgment—his death triggered a constitutional dilemma that would permanently shape how the United States handles presidential succession.

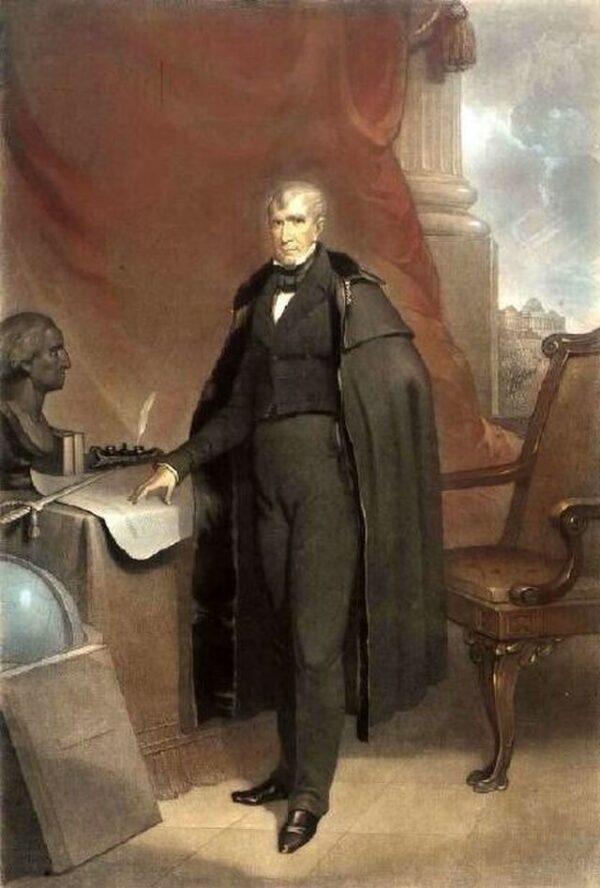

Harrison, elected in 1840 as the ninth president, rode a wave of populist enthusiasm and Whig Party support. His fame as a war hero, especially after leading American forces at the 1811 Battle of Tippecanoe, gave his campaign strong appeal. However, at 68 years old, Harrison was the oldest man elected president at the time, which worried some voters. Still, the Whigs united behind the catchy slogan “Tippecanoe and Tyler Too,” pairing Harrison with John Tyler, a Virginian selected to attract Southern voters. The campaign focused on relatable symbols—log cabins and hard cider—to promote a vision of grassroots democracy, even though Harrison came from an elite background. The strategy worked, but victory came at a cost.

On March 4, 1841, Harrison gave an unusually long inauguration speech—nearly two hours—in cold, rainy weather, refusing to wear a coat or hat. The act was meant to show strength, but it likely contributed to his decline. Within weeks, he became seriously ill. While modern historians debate whether pneumonia or a gastrointestinal illness caused by unsanitary water was the actual cause of death, at the time, he was diagnosed with a lung infection. He died on April 4, leaving the country facing an unprecedented challenge. The Constitution said that presidential power would “devolve on the Vice President,” but it was unclear whether that meant the vice president would fully become president or just act in that role temporarily.

John Tyler quickly declared himself the new President—not just acting president—and took the oath of office, moved into the White House, and assumed full authority. His assertiveness sparked controversy. Many Whig leaders, including Henry Clay, opposed him. Tyler had been added to the ticket for strategic reasons, not because he was seen as a party leader. Still, Tyler’s move stood. No one stopped him, and his actions became precedent. This “Tyler Precedent” later guided the writing of the 25th Amendment, which clarified the line of presidential succession.

Politically, Tyler’s presidency marked the collapse of the Whig coalition. He vetoed major Whig policies, including a new national bank, leading to mass resignations from his cabinet—except for Secretary of State Daniel Webster—and his expulsion from the party. Isolated and politically abandoned, Tyler still managed to exercise significant presidential power, especially in foreign affairs and territorial growth. His administration initiated efforts that would lead to the annexation of Texas, a move that escalated tensions over slavery and pushed the country closer to civil war.

Ultimately, Harrison’s untimely death was more than a personal tragedy—it was a constitutional turning point. It exposed weaknesses in the nation’s founding documents and showed how quickly a political crisis could emerge. Tyler’s bold response set a lasting precedent, proving both the flexibility and fragility of American governance. This moment became a defining episode in the development of executive power in the United States.