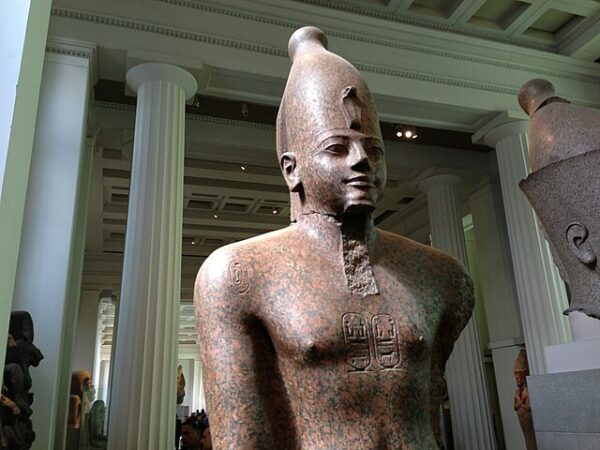

On April 16, 1457 BC, Pharaoh Thutmose III of Egypt confronted a coalition of Canaanite city-states near the strategic fortress of Megiddo in present-day northern Palestine. More than a turning point in Egypt’s imperial ambitions, the Battle of Megiddo holds distinction as the earliest military conflict documented with credible detail. Its significance stems not just from its scale, but from the remarkably well-preserved inscriptions in the Temple of Amun-Re at Karnak, offering scholars a vivid account of ancient warfare—its tactics, logistics, and ceremonial dimensions.

The conflict arose during a period of political instability following the death of Thutmose II. During the regency of Hatshepsut, who served as co-ruler and stepmother to Thutmose III, rebellious sentiments among Egypt’s Asiatic vassals simmered. When Thutmose III assumed full control, a coalition of Canaanite leaders—led by the King of Kadesh—seized the opportunity to resist Egyptian dominance. Their goal was clear: overthrow foreign rule and restore local independence. The city of Megiddo, a key junction along vital military and trade routes through the Levant, became the symbolic and strategic heart of the uprising.

Thutmose III responded with an extraordinary campaign. Marching from the Nile Delta across the Sinai Peninsula and into the Jezreel Valley, his army covered hundreds of miles in less than two weeks—a feat of speed and coordination rare for the time. Upon nearing Megiddo, the Egyptians faced a critical decision: take one of two safer, heavily surveilled routes, or gamble on a narrow, perilous mountain pass through Aruna (modern Wadi Ara). Against the advice of his generals, Thutmose III chose the latter.

This bold choice proved pivotal. The Canaanites had assumed the Egyptians would avoid the Aruna route and failed to defend it. Thutmose’s forces emerged from the pass unchallenged, catching the defenders completely off guard. What followed was not a mere encounter but a structured battle involving coordinated chariot assaults, flanking strategies, and archery volleys—early indicators of classical military organization.

Thutmose’s army, structured into three divisions named after Egypt’s major deities—Amun, Ra, and Ptah—capitalized on the surprise. The sudden appearance of Egyptian forces threw the Canaanite coalition into disarray. After a brief but fierce engagement, enemy forces retreated within Megiddo’s fortified walls, abandoning their supplies and chariots outside. Rather than storming the city, Egyptian forces besieged it—a strategy that eventually forced its surrender after seven months.

The consequences were profound. Egypt reasserted control over the Levant for the next century. Over 300 local princes were taken captive and brought to Egypt, where they were simultaneously honored and monitored—educated in Egyptian customs but held as political hostages. Meanwhile, Thutmose III extended his influence deeper into Syria and Mesopotamia, securing his legacy as one of Egypt’s most formidable military leaders.

Yet, what truly elevates the Battle of Megiddo is not only the outcome but the documentation. Likely compiled under the direction of Thutmose’s scribe, Tjaneni, the inscriptions at Karnak provide one of the earliest examples of military historiography. They detail not only the battle’s strategy and logistics—such as supply chains and marching orders—but also capture the psychological experience of warfare: the burden of command, the exhilaration of a surprise attack, and the solemn rituals observed before combat.

In this way, the Battle of Megiddo marks more than a historical event—it represents the dawn of recorded military history. It transformed warfare from myth and oral tradition into one of structured narrative, strategic insight, and lasting memory.