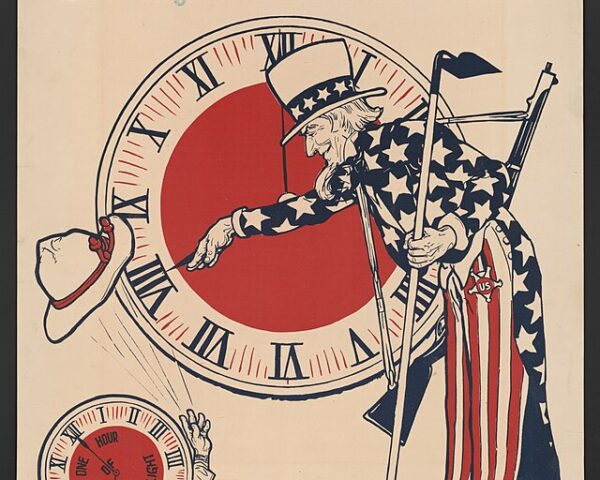

On April 25, 1901, New York became the first state in the United States to require license plates for automobiles—an unassuming administrative milestone that marked the beginning of a new era in transportation regulation. As motor vehicles began their ascent from elite novelty to practical necessity, the state’s decision to impose a registration system signaled a turning point in how society would manage the growing presence of cars on American roads.

At the dawn of the 20th century, automobiles were still rare and exotic machines. Fewer than 25,000 dotted the nation’s roads, and most were found in the Northeast. The streets of New York City—crowded with pedestrians, horse-drawn wagons, and trolleys—were ill-prepared for the new, motorized arrivals. There were no traffic signals, and laws governing vehicles were nearly nonexistent. As incidents involving reckless driving and pedestrian injuries increased, pressure mounted on lawmakers to act.

Responding to these challenges, the New York State Legislature passed a statute on April 25, 1901, requiring all owners of motor vehicles to register with the state and display identifying numbers on their cars. Rather than issue standardized plates, the law required drivers to make their own: typically painted or stenciled on leather or metal, the plates had to display the vehicle’s registration number and often included the owner’s initials. The cost of registration was $1—a modest fee that equates to roughly $35 today.

The first number issued under the new law, “1,” went to Frederick C. Baker of New York City. Like other early adopters, Baker crafted his own plate and mounted it proudly on his vehicle, most likely a Winton or Oldsmobile. Some early motorists hired blacksmiths or leatherworkers to produce more refined versions, turning these identifiers into symbols of status and civic responsibility.

While the measure may have seemed like a simple bureaucratic fix, it reflected broader cultural and technological transformations. By requiring license plates, New York acknowledged that automobiles—once considered private toys—had become public concerns. The new law signified an early recognition that freedom of movement also required systems of accountability.

Other states quickly took note. In 1903, Massachusetts became the first to issue state-made plates. Within a few years, nearly every state followed suit, creating a patchwork of registration systems that laid the groundwork for today’s nationwide vehicle regulation. These changes not only enabled police to track stolen cars and enforce traffic laws but also began generating revenue for the construction and maintenance of public roads.

Importantly, the 1901 law foreshadowed deeper shifts in the relationship between citizens and the state. As automobiles erased traditional limitations of distance and time, license plates served as tools of visibility and control. They made vehicle owners legible to the state and to one another, laying the groundwork for more sophisticated forms of oversight in the 20th century—from driver’s licenses to insurance requirements.