On May 13, 1846, the United States Congress formally declared war on the Federal Republic of Mexico—a decision that, while presented to the public as a response to a Mexican military incursion, in fact reflected the culmination of deeper ideological currents, territorial ambitions, and geopolitical miscalculations that had been gathering momentum for over a decade. The war that followed, which lasted nearly two years, would not only redraw the map of North America but also exacerbate sectional tensions in the United States and leave Mexico politically disfigured, territorially amputated, and historically humiliated.

The immediate pretext for war was an incident along the contested southern border of Texas, a region whose legal status had been in dispute ever since the Texas Revolution of 1836. After nearly a decade as an independent republic—recognized by the United States but not by Mexico—Texas had been annexed by the U.S. in December 1845, triggering outrage in Mexico City. For President James K. Polk, a committed expansionist steeped in the ideology of Manifest Destiny, the annexation of Texas was not merely a defensive act or the incorporation of a willing territory—it was the opening gambit in a broader strategy to acquire California and secure hegemony over the western half of the continent.

But Mexico, still reeling from internal instability and foreign debt, viewed Texas not as a former republic but as a renegade province. The U.S. insistence that Texas’s southern boundary extended to the Rio Grande—rather than the Nueces River, long accepted by Mexico as the territorial line—was interpreted by Mexican authorities as an unmistakable act of aggression. When Polk ordered General Zachary Taylor to move U.S. troops into the disputed zone between the two rivers in early 1846, it was effectively a provocation designed to elicit a Mexican military response—and it did.

On April 25, a detachment of Mexican cavalry attacked an American scouting party in the contested territory. Sixteen U.S. soldiers were killed or wounded. Polk seized on the incident as a causus belli. In a message to Congress laced with theatrical indignation, he declared that “Mexico has passed the boundary of the United States, has invaded our territory and shed American blood upon American soil.” The phrase, deliberately vague on the question of where the soil in question actually lay, proved politically effective. Within days, Congress authorized the use of military force. Only a small cadre of anti-slavery Whigs, including John Quincy Adams and Abraham Lincoln, voiced opposition, warning that the war was a thinly veiled land grab designed to expand slave territory and disrupt the delicate sectional balance.

Indeed, the Mexican–American War was as much about ideology as it was about geography. For the Polk administration, the war offered the chance to convert territorial ambition into historical inevitability—a belief that the Anglo-American republic was destined, perhaps divinely ordained, to occupy the continent “from sea to shining sea.” Yet this same vision, when applied militarily, revealed the fragility of America’s self-conception. The war placed the United States in the morally ambiguous position of invading a weaker neighbor, raising difficult questions about imperialism, race, and the boundaries of democratic legitimacy.

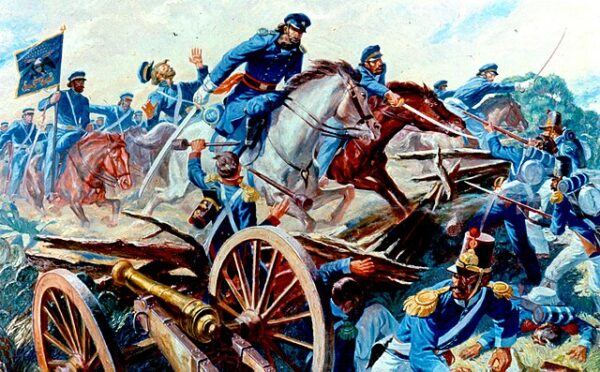

Militarily, the war was a showcase of American logistical superiority and Mexican political dysfunction. Generals like Taylor and Winfield Scott achieved a string of decisive victories, from Palo Alto to Buena Vista to the amphibious landing at Veracruz and the final, symbolic conquest of Mexico City. Meanwhile, Mexico’s fractured leadership—wracked by coups, bankrupt finances, and a citizenry skeptical of conscription—was unable to mount a sustained national defense.

The Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo, signed in February 1848, confirmed Mexico’s defeat. Under its terms, the United States acquired over 500,000 square miles of territory, including present-day California, Nevada, Utah, Arizona, and parts of Colorado, New Mexico, and Wyoming. In exchange, Mexico received $15 million and the assumption of certain American claims—compensation that, in the eyes of many Mexicans, failed to legitimize what they viewed as a national dismemberment.

Yet victory came at a cost. The acquisition of vast new territories reignited the dormant debate over the expansion of slavery—an issue that the Missouri Compromise of 1820 had temporarily suppressed but never resolved. The Wilmot Proviso, introduced during the war, sought to ban slavery in any newly acquired lands. Though it failed, it foreshadowed the explosive sectional conflicts that would culminate in civil war less than two decades later.