On May 21, 1856, the town of Lawrence, Kansas—a fledgling stronghold of free-state resistance on the contested frontier—was looted and burned by a posse of some 800 proslavery partisans under the authority of a federal marshal. Though often recast in summary as a mere “sacking,” the assault was a calculated act of political violence: a premeditated campaign of destruction designed to extinguish Northern influence in the Kansas Territory by force. Its broader significance, however, lay in what it exposed—that the Union’s constitutional architecture could no longer contain the violent contradictions of slavery and freedom within the same political space.

The raid on Lawrence was no spontaneous riot. It was a culmination. Since the passage of the Kansas-Nebraska Act two years earlier—legislation that repealed the Missouri Compromise and declared that settlers in the western territories would determine the status of slavery for themselves—Kansas had become a proxy battlefield for national power. “Popular sovereignty,” as Illinois Senator Stephen A. Douglas had optimistically styled it, proved a mirage. Missouri slaveholders, fearing the emergence of a free state on their western border, flooded Kansas with armed men to establish a proslavery legislature by fraud and intimidation. In response, New England abolitionists, mobilized through the Massachusetts Emigrant Aid Society, dispatched free-soil settlers and rifles to counterbalance the invasion. The result was not compromise but a state of low-intensity civil war.

Lawrence became the symbolic heart of that conflict. Founded by antislavery migrants and fortified with Sharps rifles smuggled in crates marked “Bibles,” the town stood as both a material and ideological threat to slaveholding supremacy. Proslavery leaders in nearby Lecompton and Franklin viewed Lawrence as a hotbed of sedition and conspiracy—a place where abolitionist newspapers like the Herald of Freedom and the Kansas Free State openly challenged the legitimacy of the so-called “bogus legislature,” and where juries refused to enforce laws criminalizing antislavery speech. To proslavery eyes, Lawrence was not merely defiant; it was insurrectionary.

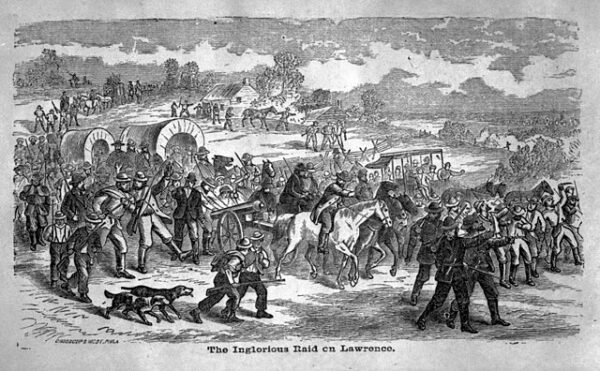

The pretext for the assault came in the form of legal enforcement. Samuel J. Jones, a Southern-born federal marshal and fervent proslavery activist, claimed authority to arrest free-state leaders for contempt of court and resistance to the laws of the territorial government. On May 21, backed by a posse that included Sheriff Jones, militia from Missouri, and a detachment of the Border Ruffians who had previously terrorized the polls, the force descended on Lawrence. No serious resistance was offered—free-state men, mindful of the political costs of a violent clash, chose not to defend the town by force. But restraint did not spare them.

Jones and his men systematically sacked Lawrence. They burned the Free State Hotel, demolished the printing presses of the Herald of Freedom and the Kansas Free State, plundered homes and businesses, and paraded through the streets with captured banners and loot. As flames engulfed the town, proslavery agitators raised a celebratory flag over the ruins, boasting that the “abolition hole” had been cleansed. No lives were lost in the immediate violence, but the message was unmistakable: antislavery thought, speech, and settlement would be punished not only with political exclusion, but with physical annihilation.

To the North, the attack on Lawrence was a watershed—a government-sanctioned assault on civil liberty, free speech, and the democratic process. Republican newspapers portrayed it as proof that the South no longer intended to engage the North as a political equal but sought to dominate it through force. Charles Sumner, the abolitionist senator from Massachusetts, rose two days later to deliver his infamous “Crime Against Kansas” speech, denouncing the proslavery faction as a lawless oligarchy and castigating South Carolina Senator Andrew Butler by name. Within 24 hours, Sumner would be bludgeoned nearly to death on the Senate floor by Butler’s cousin, Representative Preston Brooks—a literalization of the Southern threat.

The sacking of Lawrence, then, was more than a local outrage. It shattered the illusion that the conflict over slavery could be confined to debate or defused by legislative finesse. It demonstrated that the federal government—when in the hands of proslavery interests—would use its powers not to preserve order or protect rights, but to terrorize dissent and silence opposition. And it proved that the Union’s days as a neutral framework for sectional coexistence were drawing to a close. After Lawrence, after Sumner, after Bleeding Kansas—what remained was not compromise, but countdown.