By late spring 1865, the Confederacy was collapsing in pieces. Richmond had fallen, Lee had surrendered at Appomattox, and President Jefferson Davis was a fugitive. Yet the vast expanse of the Trans-Mississippi—stretching from Texas to Arkansas and parts of Louisiana—remained a Confederate holdout, largely cut off from the rest of the South after Union forces secured the Mississippi River in 1863. Within this isolated military theater, one last major Confederate force held out under the command of General Edmund Kirby Smith. That final embattled remnant would endure until May 26, 1865, when Smith surrendered at Galveston, Texas—formally ending organized Confederate resistance and closing the final chapter of the American Civil War.

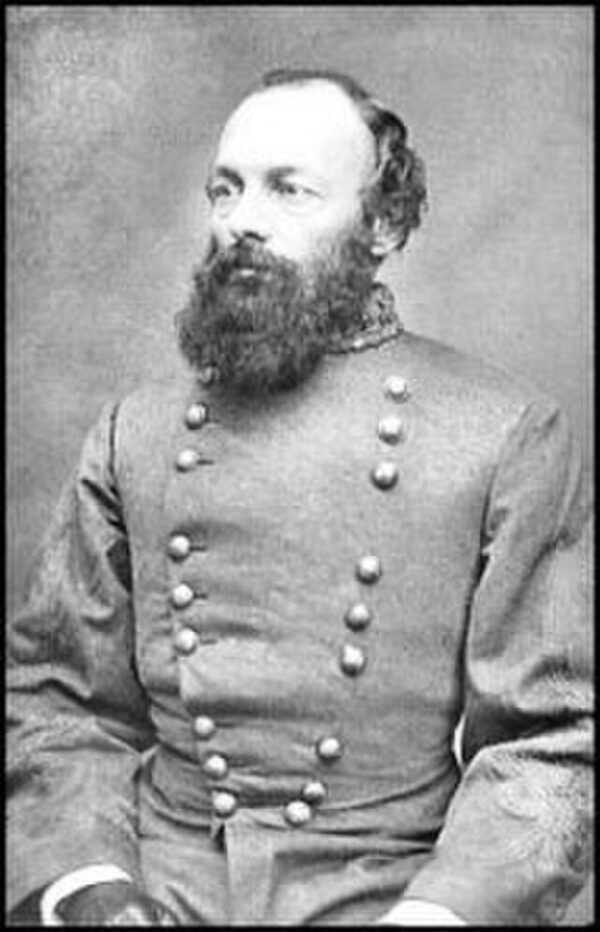

Smith, a West Point graduate and veteran of the Mexican-American War, had been promoted to full general in February 1864—one of only seven to attain that rank in the Confederate Army. He was tasked with overseeing the Trans-Mississippi Department, a vast and unruly domain where communication with Richmond was sporadic and where Confederate governance operated with near-total autonomy. After Lee’s surrender on April 9, 1865, followed swiftly by General Johnston’s in North Carolina and the capture of Davis in Georgia, Smith found himself effectively the last man standing among the Confederacy’s top brass.

The political and military context in which Smith operated had become untenable. Desertions were rampant, currency had lost its value, and morale was in freefall. Yet some Confederate officers under Smith still dreamed of prolonging the war through guerrilla resistance or seeking foreign support via Mexico. Smith himself initially entertained vague notions of rallying the Trans-Mississippi armies to continue the fight. But reality soon intruded. Even before his formal surrender, large portions of his command were already melting away. By mid-May, Smith recognized that prolonging resistance would serve no purpose beyond needless bloodshed and regional instability.

On May 26, 1865, at Galveston, Texas, Edmund Kirby Smith officially agreed to terms of surrender with Union representatives. While this event lacked the ceremonial drama of Appomattox or the scale of earlier capitulations, its symbolic importance was enormous. Smith was the last full general of the Confederate States Army to surrender a major military force. His capitulation marked the de facto and de jure end of Confederate military authority anywhere in the continental United States.

In the weeks that followed, Union forces moved in to reassert federal authority in the Trans-Mississippi. Martial law was imposed, and local governments were disbanded or reconstituted under federal supervision. The chaotic handover of power in Texas and surrounding areas was complicated by the continued presence of Confederate die-hards, the emergence of outlaw bands, and the lingering question of emancipation’s enforcement. Indeed, it was not until June 19, 1865—when Union General Gordon Granger arrived in Galveston and issued General Order No. 3—that slavery was officially declared abolished in Texas. That announcement, commemorated today as Juneteenth, owes its timing in part to the delay in Smith’s surrender.

After the war, Smith fled briefly to Mexico and then to Cuba, fearing arrest and trial for treason. He eventually returned to the United States and received a presidential pardon. In the postwar years, he lived a relatively quiet life, becoming a university professor and chancellor at the University of Nashville. He remained largely unrepentant about his role in the war but faded from public life as the Confederacy slipped into memory.

Smith’s surrender on May 26 did not erase the scars of the war—but it did draw a long and bloody conflict to a formal close. With it ended not just military hostilities, but the last flickers of an organized Confederate rebellion. What followed was a new and no less difficult chapter in American history: Reconstruction, national reunification, and the long struggle to define the meaning of freedom and citizenship in the aftermath of secession and slavery.