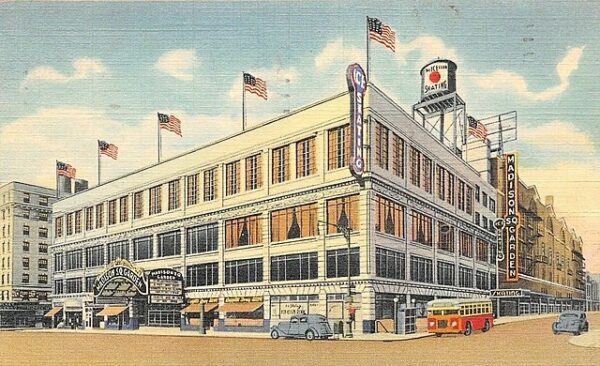

On May 31, 1879, a modest but consequential shift in New York City’s cultural topography took place: Gilmore’s Garden, a frequently repurposed arena at 26th Street and Madison Avenue, was renamed Madison Square Garden by railroad heir William Henry Vanderbilt. The name change was more than a marketing tweak—it was a deliberate act of rebranding that positioned the venue as a permanent fixture of New York’s civic identity, one that would, over time, become synonymous with public spectacle, political theater, and sporting triumph.

The site itself had already experienced a succession of identities. Originally a train depot owned by Cornelius Vanderbilt, it had been leased in the early 1870s to P.T. Barnum for circus performances, and later to bandleader Patrick Gilmore, who turned it into “Gilmore’s Garden”—a venue for concerts, flower shows, and beauty contests. But despite Gilmore’s flair for pageantry, the venue lacked staying power. William Henry Vanderbilt, seeking both profitability and prestige, stripped away the ephemeral name and anchored the building to the adjacent Madison Square Park, invoking the legacy of James Madison and the patriotic overtones of the Founding generation. The move reflected a broader ambition: to elevate the space from a mere exhibition hall to an institution that would mirror New York’s own upward trajectory.

Though rudimentary by modern standards—the original Garden was an open-air structure with wooden bleachers—the newly christened arena proved remarkably versatile. It hosted everything from boxing matches and bicycle races to political conventions and dog shows. More importantly, it offered New Yorkers a centralized stage for shared civic experience at a time when the city was rapidly becoming the nation’s financial and cultural capital. Vanderbilt’s rebranding helped forge the notion that a venue could embody not just entertainment, but identity—a place where New York saw itself reflected in pageantry, conflict, and collective celebration.

That legacy would deepen across subsequent iterations of the Garden, culminating in its transformation into a bastion of professional sports. Chief among its tenants has been the New York Knicks, founded in 1946 and permanently etched into the mythology of the arena. As one of the NBA’s original franchises, the Knicks helped define the Garden’s reputation as “The Mecca of Basketball,” not merely through championship pursuits but through the intensity and loyalty of their fanbase. Legends like Willis Reed, Walt “Clyde” Frazier, and Patrick Ewing turned routine home games into cultural milestones, infusing the building with a hard-nosed elegance befitting the city itself. Even in lean years, the Knicks have made Madison Square Garden an event in and of itself—a magnet for celebrities, global audiences, and nostalgic New Yorkers craving the city’s signature mix of grit and glamour.

The first Garden stood until 1889, when it was razed to make way for a grand Beaux-Arts replacement designed by Stanford White. That second arena would in turn be replaced twice more, each time moving slightly farther west but carrying the name—and the weight of its tradition—with it. Today’s Madison Square Garden, perched above Pennsylvania Station, continues to bear the name Vanderbilt gave it in 1879. It has evolved into more than a venue; it is a proving ground, a symbol, and, above all, a stage upon which the city’s aspirations—athletic, political, and cultural—are endlessly rehearsed and renewed.