The French Revolution crossed a fatal threshold on June 2, 1793, when François Hanriot, a failed clerk turned militant commander of the Paris National Guard, surrounded the National Convention at cannon-point and arrested 22 leading Girondist deputies—on orders not of the people, but of Jean-Paul Marat. It was not an act of democratic will, but a violent purge, and it marked the collapse of revolutionary pluralism in favor of ideological dictatorship. With that coup, the Jacobins seized control of the Revolution, and the Reign of Terror began.

The backdrop was a republic at war with itself. By mid-1793, France was gripped by famine, foreign invasion, and domestic revolt. The fragile unity of 1789 had long since splintered into hostile factions: the Girondists, moderates who favored federalism and legal restraint, and the Montagnards, radical Jacobins who believed virtue could be enforced at the point of a bayonet. The Girondists distrusted the Paris mob; the Jacobins, especially Marat, wielded it like a weapon.

Marat—gaunt, diseased, and incandescent with revolutionary fervor—had become the Revolution’s prophet of vengeance. Through his newspaper L’Ami du Peuple, he called for the elimination of the Girondists, whom he branded enemies of the poor and traitors to the Republic. Their crimes, in his telling, were not merely political misjudgments but existential threats to revolutionary justice. And in a republic where suspicion had become synonymous with guilt, that was enough.

Enter Hanriot. Elevated by the sans-culottes and utterly beholden to Jacobin authority, he mobilized thousands of armed Parisians, ringed the Convention, and pointed artillery at its doors. With Marat’s list in hand and Robespierre’s silence as assent, Hanriot demanded the arrest of 22 Girondists—names that included Brissot, Vergniaud, and Roland. The Convention, cowed by force and paralyzed by fear, capitulated.

No vote of expulsion. No legal proceedings. Just a list—and the guns to enforce it.

It was a stunning moment: the Revolution, which had overthrown monarchy in the name of liberty and representative government, now devoured its own legislature at the command of demagogues. In purging the Girondists, the Jacobins eliminated the last serious check on their power and laid the foundation for a new regime—not of law, but of terror cloaked in the rhetoric of virtue.

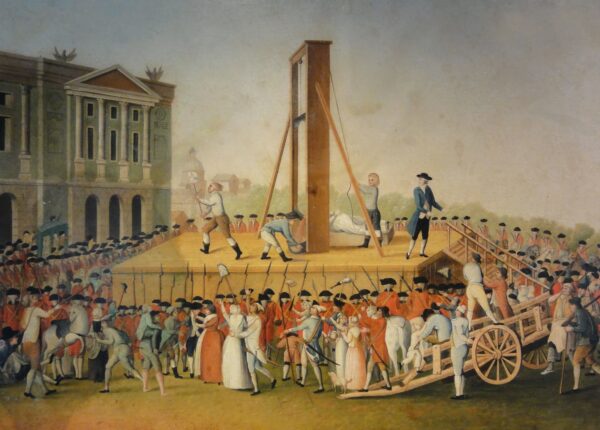

The consequences were swift and brutal. The Committee of Public Safety, now dominated by Robespierre, moved to consolidate authority. Revolutionary tribunals sprang up to process “enemies of the people,” a term so elastic it could apply to aristocrats, peasants, ex-Jacobins, or anyone who spoke out of turn. The guillotine, once a symbol of egalitarian justice, became an emblem of ideological slaughter. Between September 1793 and July 1794, thousands were executed—not for what they had done, but for what they might have believed.

Marat would not live to see the terror his purge enabled. He was assassinated by Charlotte Corday, a Girondist sympathizer, in July 1793—a death that transformed him from propagandist to martyr. Hanriot, too, would fall in time. When Robespierre was overthrown in the Thermidorian Reaction of 1794, Hanriot tried to defend him, was captured, and met the same fate as those he once imprisoned.

But the date that made it all possible—the day the Revolution turned from radical reform to armed repression—was June 2, 1793. It was not merely a power struggle. It was a declaration: that dissent would no longer be tolerated, that fear would govern the Republic, and that liberty, once promised, could be revoked at will.