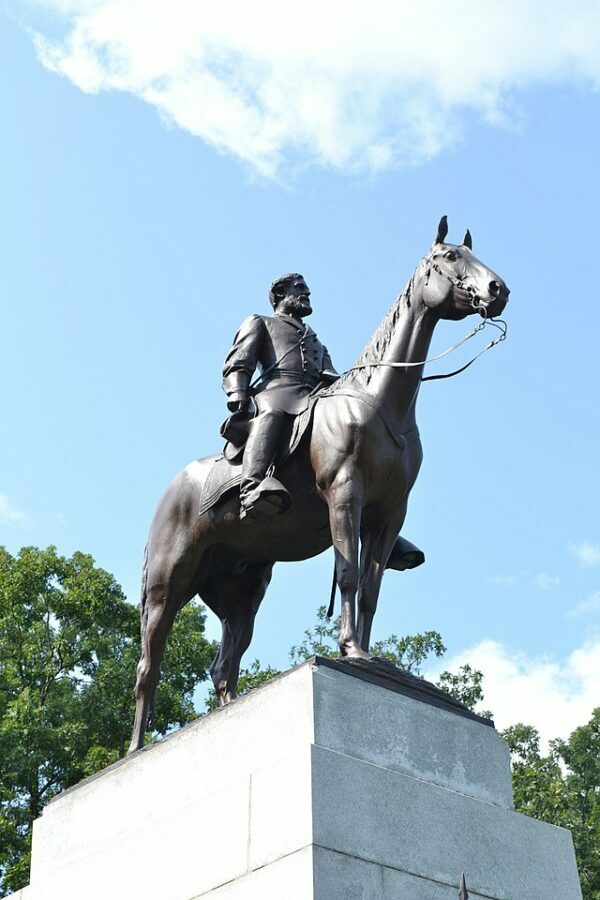

On June 3, 1863, the Army of Northern Virginia—ragged, proud, and buoyed by recent triumph—began its long march out of war-ravaged Virginia and into the lush, unbloodied countryside of Pennsylvania. At its head rode General Robert E. Lee, whose strategic genius and battlefield audacity had, time and again, defied the odds and humiliated numerically superior Union forces. But this new movement, soon known as the Gettysburg Campaign, was more than a military maneuver. It was a high-stakes incursion born of necessity, ambition, and the grim arithmetic of Confederate survival.

Lee’s first invasion of the North, halted at Antietam the previous autumn, had been inconclusive—but it had demonstrated the potential of offensive war to disrupt Union plans and reframe political realities. Now, in the wake of his dramatic and costly victory at Chancellorsville, Lee saw the opportunity to strike again. Virginia, increasingly stripped bare by two years of war, could no longer sustain his army. Nor could the South indefinitely endure the strain of a defensive war that consumed its dwindling resources with no end in sight. The solution, as Lee conceived it, was to carry the war to the enemy—physically, economically, and psychologically.

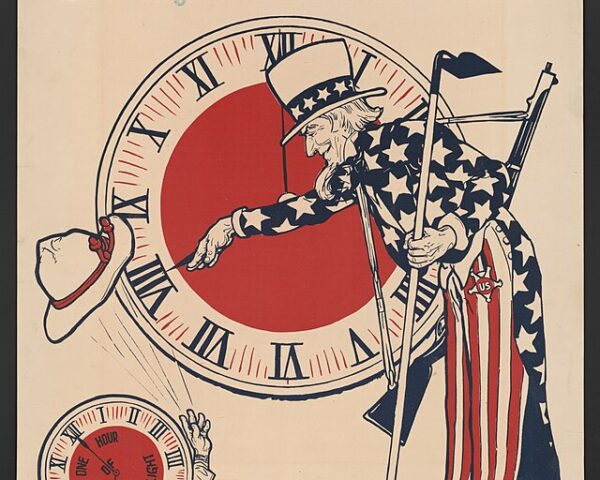

The logic behind the campaign was at once military and ideological. A successful invasion might relieve pressure on the Confederate interior, feed Lee’s army from Northern fields, and expose the North’s vulnerability to its own civilians. More than that, it might shatter Northern morale, strengthen the peace movement in the North, and tilt the fragile balance of international opinion toward diplomatic recognition of the Confederacy. In this calculus, a decisive Confederate victory on Northern soil could do what no string of Southern victories in Virginia ever had: force Abraham Lincoln’s government to consider terms.

Yet if the campaign’s aims were grand, its risks were commensurate. The Army of Northern Virginia, though formidable, had just suffered the irreplaceable loss of “Stonewall” Jackson—Lee’s trusted lieutenant and spiritual counterpart—mortally wounded by his own men in the darkness after Chancellorsville. In Jackson’s absence, Lee reorganized his forces into three corps under Generals Longstreet, Ewell, and A.P. Hill. These men were competent, even brilliant—but none commanded the mystique or intuitive bond with Lee that Jackson had cultivated.

As the army moved northward through the protective cloak of the Shenandoah Valley, Lee demonstrated his customary audacity, slipping between the Union army and Washington itself. Union General Joseph Hooker—still reeling from his defeat in May—struggled to divine Lee’s intentions and coordinate a coherent response amid the distractions of Washington’s meddling and his own crumbling authority. By the time Hooker was relieved of command and replaced by the more cautious George G. Meade, Lee had already crossed into Maryland, and his vanguard was pressing into Pennsylvania.

It was never Lee’s intention to fight a pitched battle at Gettysburg—or, indeed, anywhere in particular. The object was maneuver, not siege; disruption, not occupation. But the convergence of Union and Confederate forces in the hills and ridges around a sleepy market town would, by chance and inexorable momentum, draw both armies into the largest and bloodiest engagement ever fought on American soil. The battle would unfold not as the execution of a master plan, but as a chaotic collision of armies, each groping in fog and rumor for position, purpose, and advantage.

In hindsight, the march that began on June 3 marked the beginning of the Confederacy’s last great offensive. In seeking to bring the North to its knees, Lee had gambled the fate of his army—and, arguably, of the Confederate nation itself. For behind the confident columns and the martial brass lay a deeper unease: that time was no longer on the South’s side, and that only boldness—perhaps desperate boldness—could forestall the tide of history.