On June 4, 1919, the United States Congress approved the Nineteenth Amendment to the Constitution, formally initiating the final phase of a political struggle that had spanned more than seven decades. With the stroke of a legislative pen, Congress did not merely advance a policy—it acknowledged, at last, the civic claims of half the American population. The text was unequivocal: “The right of citizens of the United States to vote shall not be denied or abridged by the United States or by any State on account of sex.” But the clarity of that language belied the tangled path that led to it—and the unfinished work that still lay ahead.

This legislative act did not emerge in a vacuum. It was the fruit of a women’s movement forged in abolitionist fire, tempered by internal divisions over race and strategy, and animated by an evolving vision of republican citizenship. From the Seneca Falls Convention in 1848 to the militant tactics of the National Woman’s Party in the 1910s, the suffrage cause had undergone a profound transformation. It had shifted from moral appeal to political necessity, from marginal agitation to mass mobilization. But its core grievance remained the same: that a nation professing to be governed by the consent of the governed had, in practice, excluded women from the most basic mechanism of that consent.

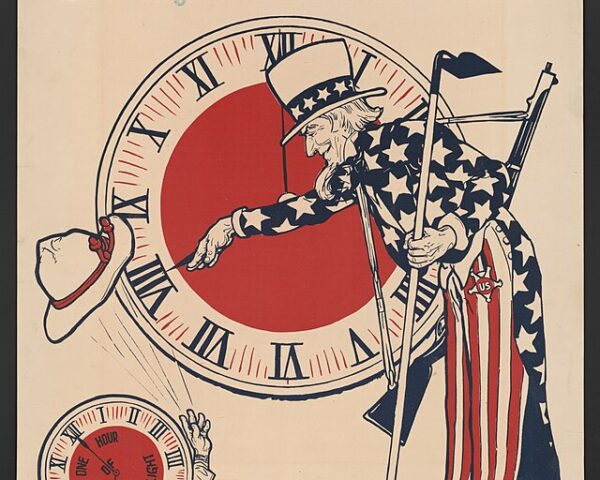

The war years accelerated the cause. With American men fighting overseas, women assumed unprecedented roles in the wartime economy and civil society. They organized bond drives, staffed Red Cross units, and entered factories in droves—all under the banner of national service. This realignment of gender and citizenship—what one might call a de facto redefinition of political belonging—did not go unnoticed. President Woodrow Wilson, once indifferent to suffrage, now declared it essential to national unity. “We have made partners of the women in this war,” he told the Senate. “Shall we admit them only to a partnership of suffering and sacrifice and toil and not to a partnership of privilege and right?”

Even so, the path to congressional approval was arduous. The House had first passed the amendment in January 1918, but it would take a year and a half of political maneuvering, backroom deals, and relentless advocacy before the Senate yielded. The final vote on June 4, 1919, met the required two-thirds threshold—but only barely. From there, the measure moved to the states, where 36 would have to ratify for it to become law.

That ratification process—ostensibly a matter of state deliberation—became a second national campaign. Suffragists redeployed their wartime networks, appealing to governors, pressuring legislators, and staging public demonstrations. Western states ratified swiftly, having already enfranchised women in state elections. But resistance remained strong in the South and in certain pockets of the industrial Midwest, where fears of racial equality and political disruption converged. Tennessee, after intense lobbying and a deadlocked legislature, became the thirty-sixth state to ratify in August 1920. The Nineteenth Amendment was certified shortly thereafter.

To be sure, the amendment did not guarantee universal enfranchisement. Black women in the South, like Black men, faced poll taxes, literacy tests, and intimidation. Native American and Asian American women remained disenfranchised by other legal barriers. But the constitutional principle—that sex could no longer serve as a basis for political exclusion—was now embedded in American law. The question was no longer whether women should vote, but how to secure the full exercise of that right in a nation still defined by hierarchy.

In this sense, June 4, 1919, stands not simply as a triumph, but as a threshold—a moment when constitutional democracy was compelled to reckon with its own contradictions, and the American republic took one step closer to the universal ideals it so often proclaimed.