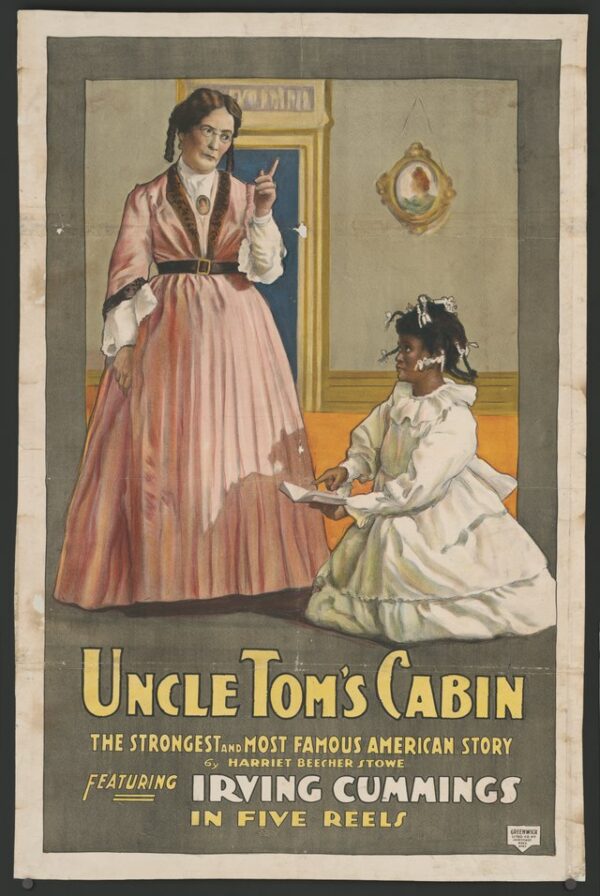

In a quiet but fateful moment on June 5, 1851, the abolitionist newspaper The National Era published the first installment of Uncle Tom’s Cabin; or, Life Among the Lowly, a serialized novel by a relatively unknown New England woman named Harriet Beecher Stowe. The debut received modest attention. But over the next ten months, as new chapters unfolded each week, Stowe’s story would seize the public imagination—and alter the moral and political landscape of the United States.

Uncle Tom’s Cabin was more than fiction—it was an act of defiance. Written in the wake of the 1850 Fugitive Slave Act, which forced free states to assist in the capture of escaped slaves, Stowe’s narrative was born of outrage and spiritual urgency. The law struck a nerve in the North, compelling citizens to participate in the machinery of bondage. For Stowe, it was personal. The grief of losing her infant son and the moral crisis sparked by the new law fused into a singular literary purpose: to expose slavery’s cruelty not through policy papers, but through the faces and voices of its victims.

Serialized publication proved to be a force multiplier. Newspapers like the Era were widely circulated and easily shared, and Stowe’s sentimental, suspense-driven style lent itself to week-by-week reading. Readers followed the lives of Uncle Tom, Eliza, George Harris, and Eva St. Clare with breathless anticipation—sometimes begging editors to publish new chapters faster. When the serial concluded in April 1852, public demand pushed the book into hardcover almost immediately. By year’s end, Uncle Tom’s Cabin had sold hundreds of thousands of copies and reached millions more through lectures, adaptations, and translations. It became the decade’s most explosive moral document—and the most hated book in the American South.

And for good reason. Stowe’s characters were not just pitiable—they were subversive. Eliza’s flight across the ice, George Harris’s declarations of manhood, Uncle Tom’s Christlike endurance—all were designed to put a human face on an institution that Southerners insisted was benign. It worked. Moderate Northerners who had long viewed slavery as a distant political headache now saw it as a profound spiritual evil. Stowe’s pen had reached where arguments failed—into the conscience of the common reader.

Southern defenders of slavery launched a furious counterattack, accusing Stowe of fabrication and hysteria. “Anti-Tom” novels poured into the market, portraying cheerful slaves and noble masters. But the damage was done. Stowe had framed the debate in moral terms that couldn’t be explained away by economic theory or paternalist myth. She had turned the enslaved into protagonists and the slave system into a villain.

Even President Lincoln, who met Stowe in 1862, is said to have quipped, “So you’re the little woman who wrote the book that made this great war.” Whether he said it or not, the sentiment captured what millions believed: that a novel, serialized in a newspaper, had done more to ignite the abolitionist cause than a thousand sermons or stump speeches.

What began on June 5, 1851, as a serialized tale in an abolitionist press became the spark that helped light the powder keg. In telling the story of life among the lowly, Harriet Beecher Stowe held up a mirror to a divided nation—and forced it to see what it had long tried to ignore.