The morning of June 24, 1314, dawned on a sodden and bloodied field near the Bannock Burn, where the fate of a nation hung by a thread. By day’s end, that thread would not snap but be reforged into iron. Against impossible odds, a battered host of Scots under Robert the Bruce annihilated the numerically superior English army of Edward II, securing not merely a battlefield victory but a seismic shift in the long and brutal First War of Scottish Independence.

For nearly two decades, Scotland had reeled under the fist of English ambition. The death of Alexander III in 1286 and the subsequent extinction of his heir unleashed a succession crisis ripe for English exploitation. Edward I—“Hammer of the Scots”—had seized the moment, imposing vassalage through force and calculation. But the Scottish spirit, though fractured, was never extinguished. Out of this crucible of humiliation rose two men who would define a generation: William Wallace, martyred in 1305, and Robert the Bruce, crowned king but excommunicated, outlawed, and on the run.

By 1314, Bruce had clawed back much of his kingdom through attrition and audacity. His campaign was not one of pitched battles but of castle razings and ambushes, psychological war waged across a ravaged landscape. Yet Stirling Castle remained—the last major English stronghold—and its impending surrender, promised by its commander if not relieved by midsummer, compelled Edward II to act. The English king marched north with a colossal host, perhaps the most formidable invasion force Scotland had yet faced: some 15,000 men, including a terrifying corps of heavy cavalry.

Bruce did not meet them head-on. He chose his ground—low-lying, narrow, and hemmed in by the Bannock Burn and bogland—where cavalry would flounder, not charge. His infantry, armed with pikes and trained in the schiltron, a formation as defensive as it was deadly, would fight not in open field but in the claustrophobic churn of mud and blood. This was no accident. It was strategic genius born of necessity.

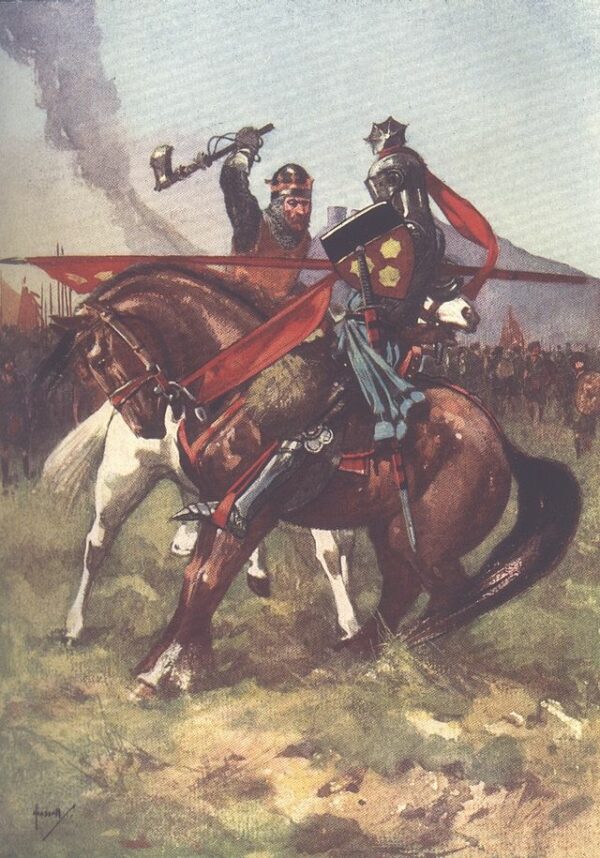

The engagement began on June 23, when English knights, overconfident and disorganized, attacked the Scottish vanguard. It was here that Bruce himself famously slew Sir Henry de Bohun with a single axe-blow to the skull—an almost mythic gesture of resolve that ignited the Scottish ranks. Yet this was merely the overture. On the following day, the full weight of Edward’s army surged forward—only to collapse into chaos. Mired in marsh and unable to deploy, the English advance stalled, then shattered. Encircled by Bruce’s schiltrons, hemmed in by geography and fear, the invaders broke and ran. Some drowned in the burn. Others were hacked down. Edward II fled in ignominy, his great expedition transformed into an ignoble rout.

Bannockburn was more than a military miracle. It was the moment the Scots ceased resisting as rebels and began asserting themselves as a nation. Though formal recognition of independence would not arrive until the Treaty of Edinburgh–Northampton in 1328, the die was cast here. Bruce emerged not just as a monarch, but as the embodiment of a sovereign people. From this triumph would flow the Declaration of Arbroath (1320), a document that framed liberty not as a royal grant but a national right—centuries ahead of its time.

On that field, amid the carrion cries and shattered helms, Scotland did not win her freedom. She proved she had never lost it.