On June 30, 1688, seven English noblemen—two earls, a viscount, a bishop, and three barons—sent a covert letter to William of Orange, inviting him to intervene militarily in England and promising their support in overthrowing King James II. Known to history as the “Immortal Seven,” these men would spark a constitutional crisis that soon erupted into the Glorious Revolution—a bloodless coup that ended the reign of an unpopular Catholic monarch and entrenched Protestant parliamentary rule in Britain.

The letter, smuggled across the English Channel to The Hague, where William ruled alongside his wife Mary (herself the Protestant daughter of James II), was a carefully crafted appeal. It alleged widespread dissatisfaction with James’s policies, warned of his alienation of the political elite and the Church of England, and asserted that the birth of a male heir in June—James Francis Edward—had prompted fears of a Catholic dynasty. The letter further promised that if William landed in England with even a modest force, many of the king’s own officers and nobles would rally to his banner.

The context behind this desperate act was years in the making. Since taking the throne in 1685, James II had pursued a policy of religious tolerance for Catholics, appointing them to military and government posts in violation of existing laws. He issued the Declaration of Indulgence, suspended Parliament, and used his dispensing power to override the Test Acts. These efforts alienated both Anglicans and dissenters, who viewed James as a monarch intent on restoring absolutism and reimposing Catholicism by royal fiat. His open admiration for Louis XIV’s France only deepened suspicions.

The situation worsened in 1688 when Queen Mary of Modena gave birth to a son. Until then, the throne had been expected to pass to Mary Stuart, James’s Protestant daughter by his first marriage, who was married to William of Orange. The arrival of a male heir displaced Mary and threatened to establish a permanent Catholic line. Though rumors swirled that the baby was an impostor smuggled into the queen’s bedchamber in a warming pan, few in the political class believed James would ever allow the Protestant succession to prevail. The Immortal Seven, fearing for their religion and political liberties, chose to act.

Their letter was signed by Charles Talbot, Earl of Shrewsbury; William Cavendish, Earl of Devonshire; Thomas Osborne, Earl of Danby; Richard Lumley, Viscount Lumley; Henry Compton, Bishop of London; Edward Russell, and Henry Sidney (who drafted the letter and later served as secretary of state under William). Though from varying factions—some former supporters of the court, others long-standing Whigs—they were united in their opposition to James’s perceived tyranny and their belief that William could act as a constitutional restorer rather than a foreign conqueror.

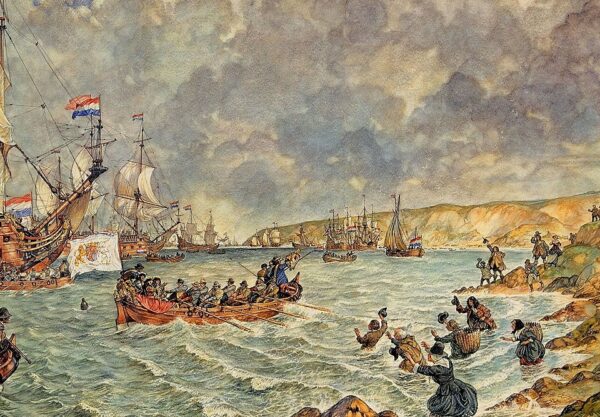

William’s response was cautious but determined. The letter provided the legitimacy he needed to present his planned invasion as a rescue mission, not an act of aggression. In a carefully worded declaration issued in October, William vowed to defend English laws, Protestantism, and the rights of Parliament. When he landed at Torbay in November with 15,000 troops, James’s support collapsed almost immediately. Key nobles defected, his army disintegrated, and his daughter Anne fled the court to join William’s cause. James, abandoned and broken, fled to France by year’s end.

The Glorious Revolution that followed—so named for its lack of bloodshed in England (though violence did erupt in Scotland and Ireland)—was as much a political reordering as a religious victory. In its aftermath, William and Mary were offered the crown jointly by Parliament under the condition that they accept the Bill of Rights (1689), which limited royal power, affirmed the supremacy of Parliament, and enshrined civil liberties. The revolution permanently ended any prospect of Catholic monarchy in Britain and inaugurated a new era of constitutional government.

The Immortal Seven’s letter reshaped the balance of power between monarch and Parliament, church and state, and helped set the ideological foundations for later democratic development. Their invitation marked one of the most consequential acts of conspiracy in Western history—cloaked in secrecy, justified by fears of tyranny, and legitimized in retrospect by its enduring constitutional legacy.