At 7:30 a.m. on July 1, 1916, whistles blew across the British trenches in northern France, marking the start of what would become the single bloodiest day in British military history. The First Day of the Battle of the Somme—a major Allied offensive against entrenched German forces—was intended to break the stalemate on the Western Front. Instead, it resulted in a catastrophic loss of life: nearly 20,000 British soldiers were killed and over 40,000 more wounded, missing, or captured in just a few hours. The scale of the disaster stunned the nation and would leave a lasting imprint on British military memory and public consciousness for generations to come.

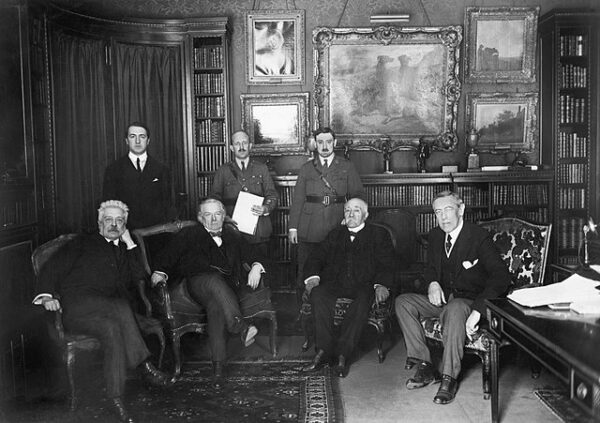

The Somme offensive was conceived as part of a coordinated effort between Britain, France, and Russia to mount simultaneous attacks against Germany and its allies in mid-1916. The goal was to relieve pressure on the French at Verdun, where a massive German assault had dragged on since February, and to exploit supposed weaknesses in the German defenses along the River Somme. Planning for the operation fell largely to British commanders, most notably General Sir Douglas Haig and General Sir Henry Rawlinson.

Haig envisioned a decisive breakthrough that would not only crush the German line but restore maneuver to a front that had been locked in static trench warfare for nearly two years. Rawlinson, more cautious, favored a limited “bite and hold” approach—seizing a few strongpoints and consolidating before pressing further. But ultimately, the operation ballooned in scale. The British high command, overly optimistic about the power of their artillery and the presumed vulnerability of the German front, believed a massive bombardment would wipe out enemy defenses, enabling infantry to advance virtually unopposed.

In the week leading up to the attack, British artillery fired over 1.5 million shells across a 15-mile front, aiming to cut through barbed wire, collapse dugouts, and demoralize the defenders. The preliminary bombardment, however, failed in critical respects. A significant percentage of shells were duds, many others were too light to damage deep German bunkers, and barbed wire remained largely intact in many sectors. Worse still, the German Army—well-trained, well-prepared, and deeply entrenched—had anticipated the assault and weathered the bombardment in reinforced shelters, emerging with machine guns ready once the firing ceased.

As British troops “went over the top” at dawn on July 1, they advanced shoulder to shoulder in straight lines—tactics better suited to 19th-century warfare than the mechanized slaughterfields of 1916. German machine guns opened fire almost immediately. In many sectors, the attackers were cut down before they reached No Man’s Land’s halfway mark. Some battalions lost over 80 percent of their men in a matter of minutes. The worst casualties fell on the “Pals battalions,” units composed of men from the same towns, workplaces, or schools—resulting in communities across Britain experiencing sudden and devastating losses.

Despite the carnage, a few gains were made in isolated pockets. In the south, near Mametz and Montauban, British and French troops were able to take their objectives, where artillery had been more effective. But these local successes were overshadowed by the staggering toll elsewhere. The 36th (Ulster) Division achieved temporary gains at Thiepval but were forced to retreat by nightfall, leaving thousands dead on the battlefield. The overall result of the day was a strategic failure for the British and a humanitarian catastrophe.

The Battle of the Somme would grind on for another four and a half months, eventually costing over a million total casualties on all sides before it ended in November. Yet nothing in the campaign’s long and bloody course would rival the trauma of that first morning. In its aftermath, the British public reacted with a mix of patriotic stoicism and rising disillusionment. The scale of the slaughter, combined with the apparent futility of the attack, would fuel criticism of military leadership, particularly of Haig—who would remain a controversial figure long after the war.