On July 3, 1913, under the humid skies of Gettysburg, Pennsylvania, a remarkable scene unfolded on the rolling hills of Cemetery Ridge. Fifty years to the day after the Confederate Army’s fateful charge across the open fields toward Union lines—a climax known as Pickett’s Charge—thousands of aged veterans gathered to commemorate the bloodiest battle ever fought on American soil. But this time, the clash ended not in cannon fire and musket smoke, but in outstretched arms and trembling hands, as former Confederate soldiers reenacted their doomed advance only to be met at the Union lines by former adversaries offering gestures of reconciliation.

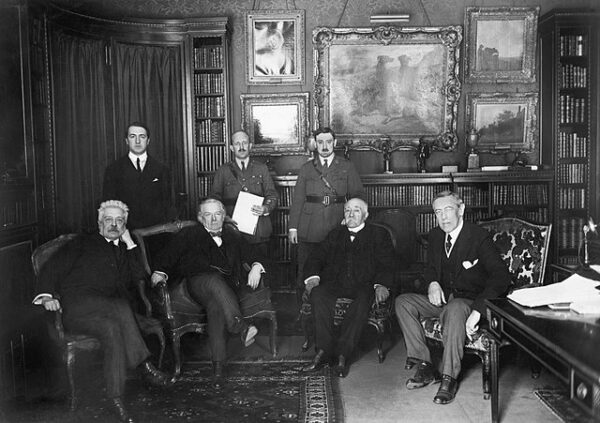

The Great Reunion of 1913 was, in scale and symbolism, one of the most ambitious commemorations of the Civil War ever attempted. Organized chiefly by the U.S. War Department, the state of Pennsylvania, and veterans’ organizations such as the Grand Army of the Republic (GAR) and the United Confederate Veterans (UCV), the event brought together over 50,000 Union and Confederate veterans, most in their seventies or eighties. It was billed as a “peace jubilee,” an effort to celebrate national unity and commemorate a shared sacrifice that had, in theory, healed the nation’s wounds.

Over the course of several days, veterans shared stories in makeshift camps set up across the battlefield. Many had not seen Gettysburg since 1863, when it was a crucible of death and destiny. Now, they walked the same ridges, ravines, and fence lines, not as enemies but as old men seeking meaning in their own twilight.

The emotional crescendo came on the final day, July 3, in a symbolic reenactment of Pickett’s Charge. Under the coordination of military organizers, several hundred Confederate veterans began a slow march from the area near Seminary Ridge toward the stone wall on Cemetery Ridge—just as they had done half a century earlier. Some leaned on canes, others were pushed in wheelchairs. The oppressive heat made the ordeal difficult, but they pressed forward with solemn determination.

At the “high-water mark of the Confederacy”—the point where Confederate General George Pickett’s division had briefly breached Union lines before being driven back—a symbolic meeting awaited. There, Union veterans stood behind the stone wall where they had once repelled the assault. As the gray-clad veterans approached, there were no shouts, no bayonets—only a hush, then the sudden sound of applause and cheers as hands reached out across the wall. Men who had once tried to kill each other now embraced, wept, and shook hands in what newspapers dubbed “the handshake across the wall.”

President Woodrow Wilson, who arrived the next day to address the assembled veterans, praised the reunion as a symbol of national healing. “We are not enemies now,” he declared, framing the event as evidence that the divisions of the past had been transcended. Yet beneath the pageantry lay a more complicated reality. While the Reunion emphasized reconciliation, it did so largely on white, male, and martial terms—deliberately avoiding mention of slavery, emancipation, or the millions of Black Americans whose freedom had been the war’s most profound consequence.

In that sense, the Great Reunion represented both a genuine outpouring of fraternity and a selective memory of the war. It privileged the valor and suffering of soldiers on both sides while eliding the ideological stakes that had defined their struggle. Nonetheless, for the veterans who met across the stone wall on that July afternoon, the moment was real. Many had lived long enough to see their enemies become brothers—not in arms, but in age, in loss, and in memory.

The image of old men in blue and gray clasping hands where they once clashed in mortal combat endures as one of the most powerful symbols of national reconciliation. Whether that reconciliation was complete, or just comforting, remains a question for later generations. But on July 3, 1913, it was, for a moment, a fact.