On July 15, 2002, John Walker Lindh—the California-born man dubbed the “American Taliban”—pleaded guilty in federal court to two felony charges: supplying services to the Taliban and carrying explosives during the commission of a felony. The plea marked a stunning conclusion to one of the most high-profile and politically charged terrorism cases in the early years of the post-9/11 era. At just 21 years old, Lindh had become a lightning rod for public outrage, a symbol of Islamic radicalization and the anxieties of a nation still reeling from terrorist attacks on its own soil.

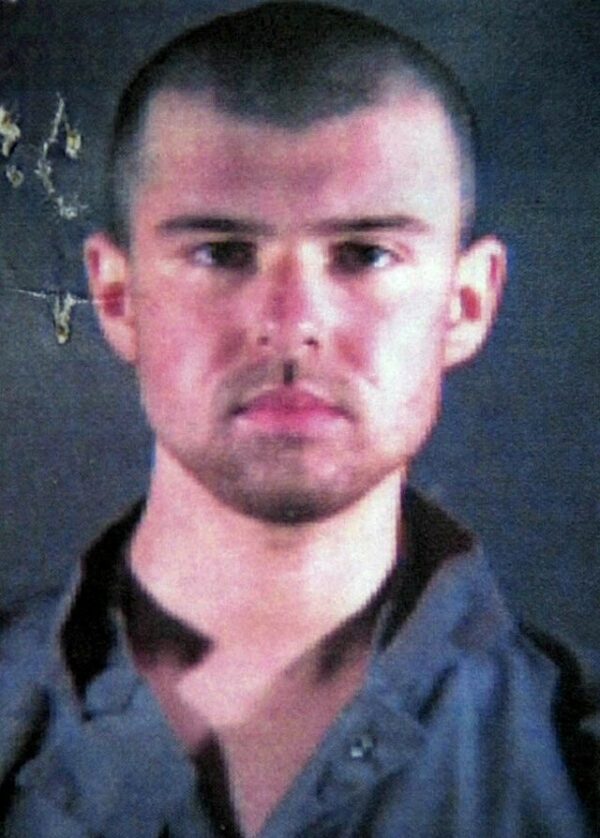

Lindh was captured by U.S.-allied Northern Alliance forces in Afghanistan in late November 2001, shortly after a prison uprising at the Qala-i-Jangi fortress near Mazar-i-Sharif that left CIA officer Johnny “Mike” Spann dead—the first American killed in the war in Afghanistan. At the time, Lindh was among a group of foreign fighters taken prisoner, and his identity as an American stunned military and intelligence officials. Images of a gaunt, bearded young man in Taliban garb—discovered hiding in the basement of the fortress—quickly saturated the media. His story seemed like a tragic anomaly, an American youth turned jihadist, fighting alongside the enemies of the United States.

Born in Washington, D.C., and raised in Marin County, California, Lindh converted to Islam as a teenager and left the United States in 1998 to study Arabic in Yemen. By 2000, he had made his way to Pakistan and later to Afghanistan, where he joined the Taliban’s military forces. His defense team would later argue that Lindh had sought religious education and was swept up in a conflict he did not fully understand. The prosecution, however, emphasized that Lindh had received training from al-Qaeda and knowingly aligned himself with a regime harboring terrorists responsible for the September 11 attacks.

Initially, Lindh faced a ten-count indictment that included conspiracy to kill Americans and providing material support to terrorists—charges that could have carried multiple life sentences. But under the terms of the July 15 plea agreement, Lindh admitted guilt to the lesser, though still serious, charges in exchange for a 20-year prison sentence and the dismissal of the most severe accusations. As part of the deal, he also agreed to withdraw any claim of mistreatment during his capture and detention, including allegations of being blindfolded, restrained, and interrogated in freezing conditions.

The plea deal was controversial. To some, it was a pragmatic resolution that avoided a potentially inflammatory and drawn-out trial that could have compromised classified information. To others, it was a lenient punishment for a man who had voluntarily joined a group that had harbored Osama bin Laden. U.S. Attorney Paul McNulty defended the agreement, saying, “Justice has been served. John Walker Lindh has accepted responsibility for his conduct and will spend the next 20 years in prison.” Attorney General John Ashcroft echoed that sentiment, framing the case as a victory in the broader war on terror.

The Lindh case would become a template—and cautionary tale—for future terrorism prosecutions. It raised enduring questions about civil liberties, due process, and the boundaries of American citizenship in a time of war. Critics of the government’s approach pointed to Lindh’s youth, lack of direct combat against U.S. forces, and the murky conditions of his arrest. Supporters of his prosecution emphasized the need for deterrence and accountability in a new era of asymmetric warfare.

Lindh served 17 years of his 20-year sentence and was released early in May 2019 for good behavior, under strict probation conditions. His case remains one of the most iconic examples of American radicalization abroad, and a symbol of how the war on terror brought faraway battlefields uncomfortably close to home.