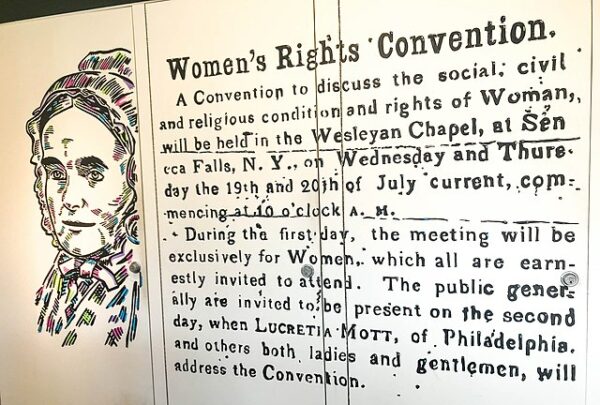

On July 19, 1848, a modest Wesleyan chapel in Seneca Falls, New York, became the unlikely cradle of a social revolution. Over two humid summer days, nearly 300 women and men gathered to launch what would become the organized women’s rights movement in the United States. Known as the Seneca Falls Convention, the event marked a decisive break from the prevailing gender norms of the 19th century and issued a bold challenge to a society that denied women full citizenship, legal autonomy, and basic civil liberties.

The convention was largely the work of Elizabeth Cady Stanton and Lucretia Mott, two veterans of the abolitionist cause who had chafed at the subordinate role assigned to women even within progressive reform movements. Their frustration reached a boiling point in 1840, when they were denied full participation at the World Anti-Slavery Convention in London. That experience galvanized Stanton and Mott to address the systemic inequalities faced by women in their own country. With the help of Martha Coffin Wright, Mary Ann M’Clintock, and Jane Hunt, they planned the Seneca Falls meeting in less than a week—an extraordinary feat given the era’s limited communication methods and prevailing domestic expectations.

The convention opened on July 19 as a women-only gathering, with about 200 attendees. Stanton, who would emerge as one of the movement’s most enduring voices, read aloud a document that would serve as both manifesto and provocation: the Declaration of Sentiments. Modeled after the Declaration of Independence, it began with the familiar phrase, “We hold these truths to be self-evident: that all men and women are created equal.” This was no mere rhetorical flourish; it was a direct indictment of a legal and social order that had systematically excluded women from public life, property ownership, education, and political voice.

The Declaration cataloged 18 grievances against the male-dominated state, paralleling the list of complaints Jefferson had levied against King George III. Among its charges: women were denied the right to vote, lacked legal identity once married, were shut out of higher education, and were subject to a moral double standard. At its heart was the radical demand for suffrage—a demand that many, even among reformers, considered outlandish.

The second day, July 20, was open to men, and among those in attendance was Frederick Douglass, the formerly enslaved abolitionist and newspaper editor. Douglass spoke passionately in favor of the resolution for women’s suffrage, helping sway a divided audience. Of the 300 attendees, 100 signed the Declaration of Sentiments, including 68 women and 32 men. While the document drew widespread ridicule in the press—one paper mocked it as “the most shocking and unnatural event ever recorded in the history of womanity”—its impact was profound.

The Seneca Falls Convention did not, by itself, transform women’s legal status or win them the vote. But it ignited a movement. In the decades that followed, Stanton would partner with Susan B. Anthony to build a national campaign for women’s suffrage. The National Woman Suffrage Association and the American Woman Suffrage Association, later merged into the National American Woman Suffrage Association, traced their lineage to that July gathering.

The convention also reframed the debate. It forced Americans—lawmakers, clergy, editors, husbands—to grapple with the logic of gender equality. By casting women’s rights within the familiar framework of American liberty and republican self-government, the Declaration of Sentiments appealed not only to abstract justice but to the nation’s founding ideals.

Though it would take another 72 years for the 19th Amendment to guarantee women the right to vote, the seeds were sown in Seneca Falls.