On July 21, 1865, the dusty market square of Springfield, Missouri, became the unlikely stage for a deadly and historic confrontation. In a moment that would echo across dime novels, silent films, and American folklore, James Butler “Wild Bill” Hickok faced off against Davis Tutt in what is widely regarded as the first true western-style showdown—a face-to-face duel with pistols at high noon.

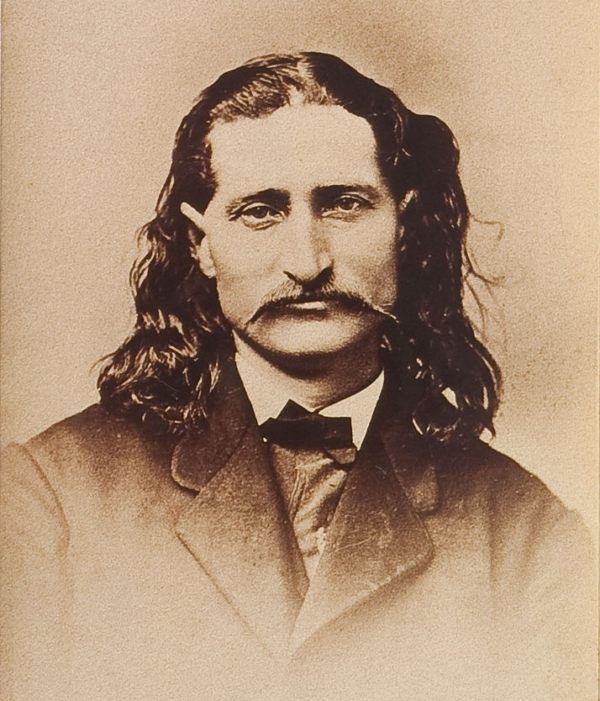

The clash was not the product of banditry or law enforcement, but a personal dispute turned deadly. Hickok, a former Union scout and gambler known for his sharp shooting and flamboyant appearance, had once been friendly with Tutt, a former Confederate soldier. Both men frequented the gambling halls of Springfield and shared a tenuous respect, but underlying tensions simmered—fueled by money, pride, and rumors of romantic entanglements.

The immediate cause of the quarrel was a gambling debt. Tutt claimed Hickok owed him $40 from a poker game, a sum Hickok disputed. As tensions escalated, Tutt reportedly seized Hickok’s prized pocket watch as collateral—an act not merely of financial retaliation, but a public insult. In the culture of the time, especially among frontier gamblers and veterans, such an affront demanded satisfaction.

The next day, as townspeople gathered in Springfield’s central square—then a muddy, open area ringed by shops and saloons—Tutt appeared with Hickok’s watch prominently displayed on his hip. Hickok warned him not to parade the watch in public, but Tutt ignored the warning. Around 6 p.m., Hickok strode deliberately into the square, stopping near the courthouse. Witnesses would later recall the silence that fell over the plaza as the two men faced each other across a distance of about 75 yards—far greater than typical pistol dueling range.

Both men drew their weapons. Tutt fired first—and missed. Hickok then calmly took aim and returned a single shot from his .36 caliber Navy revolver. The bullet struck Tutt in the chest. Staggering, he managed to walk a few paces before collapsing and dying.

Though Hickok immediately turned himself in, he was ultimately acquitted of manslaughter. His defense argued that he acted in self-defense and under the rules of honor that governed frontier disputes. The verdict underscored the unique legal and cultural codes that governed justice on the edge of the American frontier.

News of the duel spread quickly. Newspapers across the country picked up the story, and Hickok’s reputation as a deadly and fearless gunman was cemented. Within a year, Harper’s New Monthly Magazine published a sensationalized account of his exploits, transforming him into a national celebrity and laying the groundwork for the archetype of the Western gunfighter.

Unlike the formalized European duel, which involved measured paces and seconded terms, the shootout between Hickok and Tutt was spontaneous, public, and shaped by the rough codes of honor of post–Civil War America. It helped forge a uniquely American genre—one in which justice was meted out at the barrel of a six-shooter, and courage was tested not in courts but under the open sky.