On July 27, 1299, a frontier chieftain named Osman I led his warriors across the Byzantine border and launched a raid into the territory of Nicomedia, a strategic outpost in northwestern Anatolia. According to Edward Gibbon, the English historian best known for The History of the Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire, this incursion marked more than a mere skirmish—it symbolized the birth of a political entity that would grow into one of the most powerful empires in history: the Ottoman Empire.

Though modern scholarship debates the precise date and significance of this event, Gibbon and many others have traditionally regarded Osman’s campaign of 1299 as the foundational moment of Ottoman statehood. At the time, Anatolia was a fractured landscape. The Seljuk Sultanate of Rum—once the dominant Muslim power in the region—had collapsed into disorder following Mongol invasions and internecine strife. In its wake rose dozens of small, competing Turkish principalities known as beyliks. Osman’s principality, based in the town of Söğüt, was one of the least significant—until his ambitions took it beyond the boundaries of tribal raiding.

Osman’s foray into Nicomedia was more than opportunistic raiding; it was a challenge to the weakening Byzantine Empire, whose hold over its Anatolian provinces had grown tenuous. The Byzantine Empire, in the waning years of the 13th century, was a shadow of its former self—beset by internal revolts, civil wars, and external threats from both Latin crusaders and Turkish warlords. The rural lands around Nicomedia (modern-day İzmit, near Istanbul) were lightly defended and ripe for conquest.

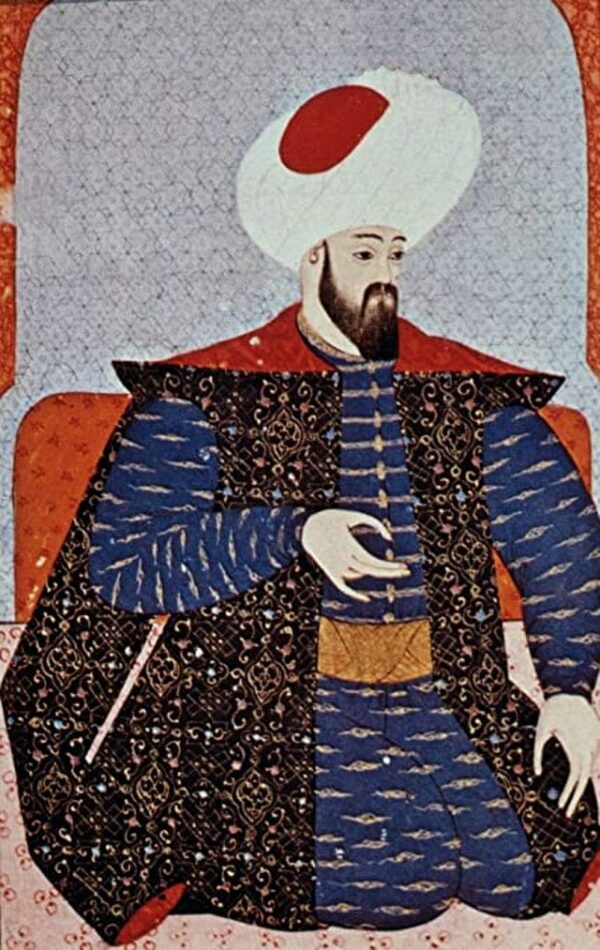

The historical Osman remains an elusive figure, and the sources documenting his life are sparse, often compiled decades or even centuries after his death. Nonetheless, oral traditions and later Ottoman chronicles depict him as a charismatic leader and devout Muslim whose rise was divinely sanctioned. According to legend, he experienced a prophetic dream in which a great tree grew from his chest, its branches covering the earth—interpreted as a symbol of future imperial greatness. Whether myth or metaphor, the symbolism became central to the Ottoman identity.

Osman’s seizure of territory near Nicomedia in 1299 set in motion a transformation from obscure border principality to rising empire. His military ventures relied heavily on ghazi warriors—fighters for the faith—who were drawn by the prospect of spoils and religious duty. These Islamic holy warriors provided both manpower and legitimacy, framing Ottoman expansion as part of a broader struggle against Christian Byzantium.

Over the next several decades, Osman’s successors would continue this momentum. His son, Orhan, captured the city of Bursa in 1326, establishing it as the first major Ottoman capital. From there, the Ottomans expanded across the Marmara region and into the Balkans, taking advantage of Byzantine weakness and disunity among rival Christian kingdoms. By the mid-15th century, the Ottomans would achieve what Osman had only dreamed of: the conquest of Constantinople, the ancient capital of the Byzantine Empire.

Though the precise historicity of the 1299 Nicomedia campaign remains contested, its symbolic value is immense. It represents the moment when a minor Anatolian warlord began to construct not merely a military power, but a state—a polity grounded in Islamic legitimacy, administrative organization, and military prowess. Edward Gibbon’s acknowledgment of this date underscores the significance later historians have attached to the event. Gibbon, though writing from a Western Enlightenment perspective and often critical of Islamic governance, recognized the importance of Osman’s rebellion as the origin point of a formidable imperial legacy.

From a small raiding party near Nicomedia emerged an empire that would dominate Southeast Europe, the Middle East, and North Africa for over six centuries. Osman I may not have foreseen the full scope of his descendants’ achievements, but July 27, 1299, remains the traditional starting point of a dynasty that would shape the course of world history.