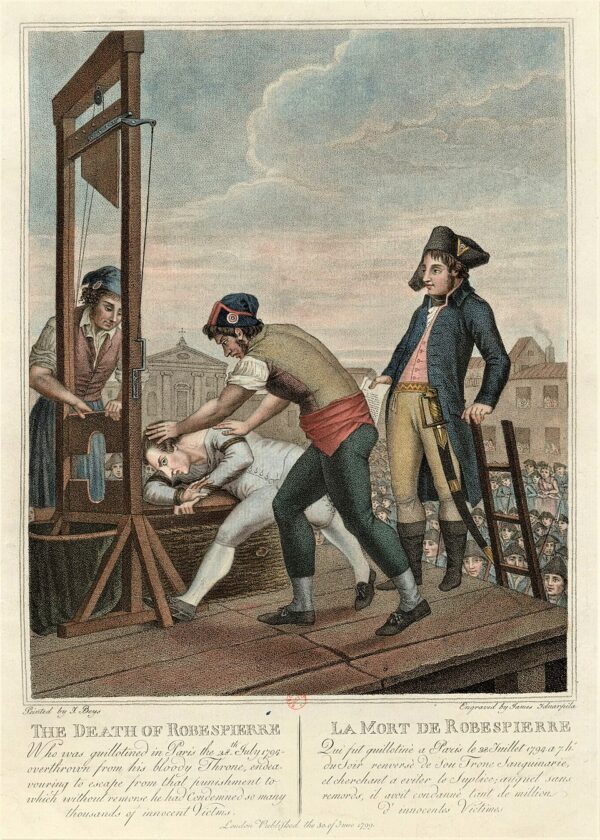

On July 28, 1794 (10 Thermidor, Year II in the insane French Revolution calendar), Maximilien Robespierre, the architect of the French Revolution’s most radical and blood-soaked phase, was executed by guillotine in Paris. Alongside him fell his loyal lieutenant Louis Antoine de Saint-Just and twenty fellow Jacobins, signaling the dramatic end of the Reign of Terror and the beginning of a new political era in revolutionary France.

Robespierre had risen to prominence as a lawyer and member of the Estates-General in 1789, quickly distinguishing himself as a fierce advocate for virtue, equality, and the incorruptibility of the revolution. With an unwavering belief in the general will and the moral necessity of terror, he came to dominate the Committee of Public Safety—France’s de facto executive authority during the most violent stretch of the Revolution.

Saint-Just, younger and equally uncompromising, was known as the “Angel of Death.” He fused icy eloquence with chilling idealism, justifying mass executions as necessary to purify the republic. Both men viewed the guillotine not as a tool of vengeance but as a means of defending the Revolution against internal and external enemies—royalists, foreign powers, and anyone insufficiently zealous in their commitment to revolutionary ideals.

Yet by mid-1794, their power had begun to alienate even their allies. Robespierre’s increasingly autocratic tendencies, coupled with his cryptic threats and refusal to name those he deemed traitors, bred paranoia in the National Convention. On July 26, he delivered a speech warning of a new purge—without specifying the targets. Deputies who once feared him now feared not acting.

The following day, July 27, a coalition of moderates and former radicals acted decisively. In a chaotic confrontation on the Convention floor, Robespierre, Saint-Just, Georges Couthon, and other Jacobins were denounced and arrested. A failed rescue attempt by the Paris Commune only added to the turmoil. Robespierre and his allies briefly sought refuge in the Hôtel de Ville, but they were captured in the early hours of July 28 after a standoff. Robespierre, shot through the jaw—possibly in a suicide attempt—was dragged to the Revolutionary Tribunal and sentenced without trial.

That same afternoon, Robespierre, Saint-Just, and their supporters were guillotined at the Place de la Révolution, the very spot where they had sent thousands to die. Witnesses noted the irony as the crowd—once cowed into silence—now erupted in cheers at their demise. Robespierre’s execution marked the symbolic end of the Terror.

In the aftermath, a period known as the Thermidorian Reaction set in. The revolutionary government dismantled the machinery of terror, curtailed the powers of the Committee of Public Safety, and executed or exiled remaining Jacobins. Paris, once governed by the guillotine’s shadow, gradually reopened its salons and theaters. Though the republic survived, it would soon lurch toward military dictatorship under Napoleon Bonaparte.

Historians have long debated Robespierre’s legacy. To some, he was a martyr of principle, destroyed by cowardly moderates who lacked the courage to see the Revolution through. To others, he was a fanatic who betrayed the Revolution’s ideals through bloodshed and repression. The truth lies somewhere in between: a man of deep conviction, ultimately undone by the very absolutism he sought to destroy.

July 28, 1794 thus stands as a defining moment not just in the French Revolution, but in the broader history of political extremism. It reveals the perils of ideological purity and the tragic paradox that revolutions often consume their most fervent apostles.